By JAN McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

For 45 minutes, two former Ohio governors from opposing parties sat side by side on stage – neither calling the other vile names or exchanging baseless barbs. It was a refreshing reminder that democracy doesn’t have to be dirty and divisive.

This was the inaugural leadership luncheon held by the newly created Democracy and Public Policy Research Network in the Department of Political Science at Bowling Green State University on Tuesday.

The highlight of the luncheon, attended by a crowd of 520 people in the BGSU ballroom, was the discussion by former governors Richard Celeste and Bob Taft on leadership, civility and public service.

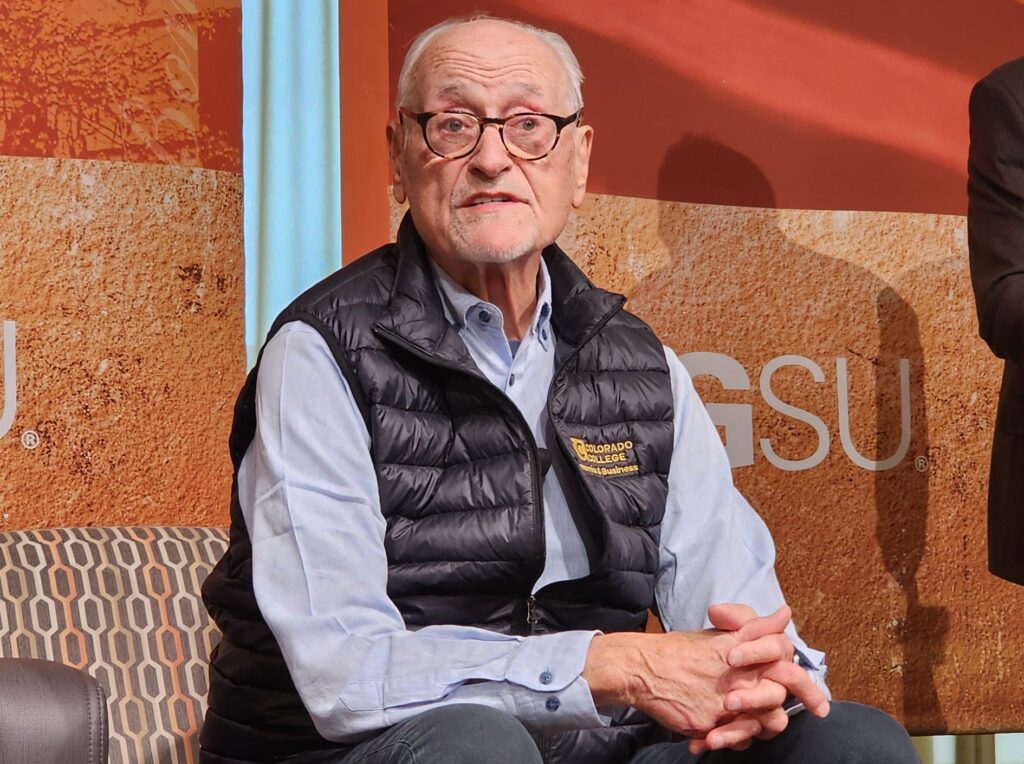

Taft, the Republican dressed in a traditional navy blue blazer, gray slacks and red tie, was governor from 1999 to 2007. Celeste, the Democrat wearing a puffy vest, denim and rainbow socks, was governor from 1983 to 1991.

Both men graduated from Yale. Both worked in the Peace Corps. Both navigated Ohio through difficult times.

Randy Gardner, the network advisory board chair, who worked with both of the former governors while serving in the Ohio House and Senate, peppered Taft and Celeste with questions. Following are some of the questions posed by Gardner.

Why public service?

Celeste pointed to two family influences – his father, who served as mayor of Lakewood, Ohio, and his grandma, who planted a seed of public service.

“To the mayors in this room – that’s the toughest job in politics,” he said.

The real lure into public service occurred when Celeste was in junior high, and he traveled by bus to Washington, D.C., with his grandmother.

The Taft family has a deep history in public life, with Bob Taft’s father and grandfather serving in the U.S. Senate, his great-grandfather serving as president and Supreme Court justice, and his great-great-grandfather serving as secretary of war and U.S. attorney general.

Bob Taft said the idea of working in the private sector never entered his mind.

Gardner thanked Celeste for taking the unusual step of appointing Gardner’s predecessor in the Ohio House (Robert Brown, a Republican) to a cabinet position in 1984, thus freeing up the seat in the House for Gardner.

Celeste said appointing someone from the opposing party seemed right. “I felt that a cabinet needed to represent the state of Ohio.”

Biggest challenges as governor?

Both Celeste and Taft came into office when the national economy was struggling.

Taft took over as governor soon after the Ohio Supreme Court had declared the state’s process for funding public schools as unconstitutional. School buildings throughout the state were in horrible conditions, he said.

So Taft initiated a 12-year program to rebuild Ohio schools. By the time he left office, building projects were underway in nearly half the state’s school districts.

Facing a lack of jobs to keep young people in Ohio after they graduated, Taft set about bringing new companies and new products to the state.

Celeste inherited an unemployment rate of 14% and a deficit of $500 million when he took office. Raising taxes was “not a popular thing,” but he knew the first step had to be getting Ohio back on track.

Not long after, Celeste was faced with the tanking of Home State Savings & Loan, which threatened to take down 60 state regulated savings and loans. Celeste again made the unpopular decision to temporarily close those savings and loans offices, denying an estimated 500,000 Ohioans access to their money.

That decision resulted in preservation of all the savings in those banks. The only person to lose was the CEO of Home State, Celeste said.

Celeste said the measure of a true leader can often be gauged by “how you deal with the unexpected.”

Balancing budgets

For all the high school and BGSU students in the ballroom, Taft pointed out the big difference between state and federal budgets.

“The state government has to balance their budgets,” he said.

Though Taft liked dealing with dollars – “I love budgets,” he said – it was not a pleasant task during the recession. He was forced to reduce expenses, and had to scale back childcare funding. “I still regret that,” Taft said.

Celeste came into office after his predecessor, James Rhodes, had promised $30 million to Honda to locate an assembly plant in Ohio. Celeste opposed that money going to Honda, with U.S. automakers already having plants in the state.

“We shouldn’t be incentivizing another car company,” he said.

Celeste said he had to inform Honda officials that while Rhodes had promised them money, he didn’t put those funds in the state budget.

“I don’t have $30 million,” Celeste said he told Honda. “We weren’t going to hand them bundles of money.”

But with Ohio’s jobless rate ticking upward, and Honda forecasting 1,200 new jobs in 12 months, Celeste negotiated with the company for work the state could provide such as a road widening and railroad stub. The plant was built and jobs were created – with Ohio footing a far smaller portion of the expense.

Confrontational political climate

Both former governors said they are troubled by the current state of national politics.

Times have certainly changed, from when Celeste packed his family in an RV and traveled around Ohio campaigning for office. Those cross-state journeys resulted in improved rest areas dotting Ohio’s highways, he said, recalling taking a sledgehammer to one of the old rest stops.

“I believe today very few people get real joy in governing,” he said. “You have the opportunity to make a difference in people’s lives.”

Now, the U.S. is in a dangerous era where politicians vilify people who disagree with them.

“I worry about where we are as a country,” Celeste said.

People must be willing to stand up for those being discriminated against, he said.

“I think all of us will be called upon,” to stand up for what is right.

Taft said he still sees committed citizens involved in their cities, townships, schools and county governments. But nationally, it’s not the same.

“It has become so polarized, so nasty,” he said. And that has led to little work being done at the national level.

“Major issues aren’t being addressed,” he said, listing off the lack of a coherent immigration policy, Medicare, Social Security, energy, the environment and climate change.

“I don’t believe government is the problem,” Taft said. “We need good people going into government.”

Advice for young people

Taft said he was pleased to see so many students in the room, and gave them bits of advice on governing with civility and collaboration.

“Inform yourself about what’s going on,” he said. “Practice civil dialogue,” with people who have different opinions. “That can be a very educational experience.”

And don’t be afraid to ask questions.

Taft encouraged the students to get involved in their communities and hold elected officials accountable for addressing needs.

Celeste urged the youth to find something they feel deeply about. Then “get involved and get engaged.”

“Be prepared for serendipity,” he said. While at Yale, Celeste felt alienated by the “preppies.” He was active in the Methodist Church, and was asked to testify against the draft to a House committee. That chance happening led to Celeste entering the Peace Corps and working with the U.S. ambassador to India.

“Be bold in how you speak,” and willing to create “good trouble,” he said, quoting John Lewis.

“All of us should be willing to get knocked down” and get up again, Celeste said.

Bipartisan leaders left

The governors were asked to name effective leaders willing to work across party lines. Both named each other first.

Taft cited George Voinovich and Rob Portman as Republicans who worked across the aisle, and U.S. Senator Elissa Slotkin, D-Michigan.

“I hold high hope for her,” Taft said.

Celeste named Slotkin and U.S. Senator Michael Bennett, D-Colorado.

“I’m distressed that there aren’t some folks who stand up when the president is doing nonsensical things,” Celeste said.

Celeste said he respected the late John McCain for speaking his mind. “I miss that,” he said.

In closing

BGSU President Rodney Rogers acknowledged the civil discussion from the two former governors. Despite their differences, Rogers pointed out their common commitments to education, improving the economy, collaborating, dealing with unexpected crises, and being open to opportunities presented by serendipity.

“These two gentlemen have created a lot of public good,” Rogers said.

Founded in the fall of 2024, the Democracy and Public Policy Research Network at BGSU will conduct nonpartisan research, polls and policy briefs that educate and inform the learning and greater community and policymakers in Ohio and beyond.