By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Mae Jemison brought the world of space travel down to earth in her talk Monday in Bowling Green Monday.

The presentation in the Performing Arts Center was sponsored by the Wood County District Public Library Foundation, the second in what’s planned to be annual series.

Jemison has a long list of accomplishments— first female African-American astronaut, doctor, researcher, dancer, teacher, and, as was evident during her talk, storyteller.

The research that has launched humans into space and kept them there performing scientific experiments, isn’t only done by people in lab coats. That research started thousands of years ago when our ancestors looked into the sky and noticed the movement of the stars, Jemison said.

“My parents were the best scientists I ever knew.” Her father was a carpenter and her mother was a school teacher. “They were always asking questions.”

Her own voyage started when she was little and looked up at the sky and wondered if others on the other side of the globe who were looking at the night sky saw the same stars in the same places.

“I always assumed I’d go into space,” Jemison said.

She loved dinosaurs and astronomy “because they really are where we come from.”

That voyage took her into space as a mission specialist on the space shuttle Endeavor in 1992, and continues through her work with the 100 Year Starship (100YSS) project which is researching what it would take to travel to the nearest star within 100 years.

That star Alpha Centauri is 25 trillion miles away from earth.

The technical challenges, Jemison said, are formidable. For a journey that would last 40 years, food would need to be grown on the craft and a source of power other than liquid fuel would have to be developed. This would look nothing like space flight now.

But human behavior poses the greatest barrier, she said. How would 5000 people manage on the long flight to the nearest distance star?

Jemison who worked as a doctor in the Peace Corps in Liberia and Sierra Leone, said there is no conflict between meeting the needs of impoverished people on earth and exploring the universe.

The technologies developed, such as GPS and MRI, through the space program have helped human beings.

And seeing the image of the earth from outer space confirms how connected people are.

But while exploring other worlds, people need to take care of their home planet.

She called for radically reducing global emissions, re-absorb excess carbon dioxide, cut pollution, and preserve biodiversity. All the while, she said, we must increase the quality of life for millions around the globe who need access to water, food, and power.

“We have sufficient knowledge and tools,” Jemison said. “But our stumbling block is we have insufficient understanding of our connections.”

Technologies can help. She told of a project in Mali where the female elders of a village managed the creation of solar installation that brought power to their village. It was inspired by a similar project in India, where the African grandmothers traveled to be trained by their peers.

Why grandmothers? They will stay in the village, Jemison said. They will not take their skills to the city or abroad.

This is not a matter of taking care of the earth — the earth will survive, she said. Whether humans survive is the issue.

People will survive only if everyone is involved.

Jemison, 63, spoke about growing up in the 1960s. To many it was a time of chaos. Growing up on Chicago’s South Side, she was as well aware of the troubles. During the riots that came in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., she prayed that her father would get home safely from work. Later that year the city erupted again during the Democratic National Convention, and she watched the National Guard assemble in a playground.

But to her it was a time when people from all over the world, of all ethnicities, of all ages, demanded to be included. Having everyone involved is necessary to address the world’s problems.

And it was a time of the expansion of knowledge. “We were discovering new subatomic particles every day.”

As people create the future, she said, the element most needed is compassion. She resents when people dismiss her as a “bleeding heart.”

“There is nothing wrong with caring for people,” Jemison said, during the question and answer section of the presentation.

Her audience was filled with young girls.

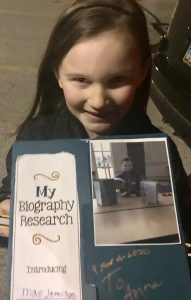

Anna Gregory, 8, had come with her mother, Alison Gregory, a BGSU graduate, from Lakewood to hear Jemison.

The trip was worth it, she said.

She portrayed the astronaut in her school’s wax museum, and she got the pamphlet she created for the project signed by her hero.

Asked why she wanted to come all this way, Anna said: “Well, I love space. I have a space bedroom.”

This passion was inspired when her “Grandma Jo Jo” sang her a song about the planets.

“Sometimes at night time I just pull up my blinds and look out my window,” Anna said. “It’s like a dream.”

Jemison encouraged her audience to look up. “The sky,” she said, “is where we find ourselves.”