By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

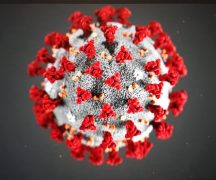

For six months now, many in the most vulnerable generation have been sequestered away for their own protection from COVID-19. But some worry that separation is taking a toll – and to some may be a death sentence.

“I really believe we’re killing our people with loneliness,” said Stephanie Rine, of Bowling Green.

Rine, whose mother lives in a Bowling Green long-term care facility, has watched her mom’s health decline during the months with no visits allowed from those on the outside.

“These are their last years, and we’re making them suffer in isolation,” Rine said.

Abundance of caution

Across the country, long-term care facilities are desperately trying to keep COVID from entering homes. Earlier this spring, when COVID first became a household term, some local nursing homes saw outbreaks among residents and staff. Some local facilities are still trying to get the virus under control.

“We know what happens when COVID gets in a nursing home,” said Jeff Orlowski, director at Wood Haven Health Care.

The precautions have worked for Wood Haven.

“As of today, we have not had any COVID cases,” Orlowski said, stressing that he wants to keep it that way. And one of the best ways to do that is to keep outsiders from entering.

“Nine-five percent of our families are 100% for us doing what we are doing to keep their loved ones safe,” he said.

At the same time, Orlowski understands the health value of family visits for nursing home residents. Families were initially allowed only visits through windows – which was far from an ideal system.

In the summer, when the state started allowing outdoor visits, many long term facilities scrambled to set up a process that would work for families and be as safe as possible.

“We don’t want to take any chances,” Orlowski said.

But now, as cold weather approaches, families are wondering how these visits can continue.

“They are talking at the state level to figure out what we will do when the cold months come,” Orlowski said.

Wood Haven does make some exceptions, allowing “compassionate visits” for families.

“Most of the compassionate visits we do are for end of life cases,” he said. However, exceptions are also made if a resident is showing serious symptoms of depression or decline.

“Any change of condition, we notice,” Orlowski said. “And if we get any word from family about declining, then we go to compassionate visits.”

Separation anxiety

For senior citizens who thrive on socializing, the pandemic has been crippling – especially those in long term care facilities who have been shut off from family.

Dr. Nancy Orel, executive director of research at the Optimal Aging Institute at BGSU, expects that future studies of this pandemic period will show drastic cognitive and social declines for seniors.

“For those individuals who love to socialize and love to have visits from their family, this can be devastating,” Orel said.

The extent of the impact can be seen in the language some seniors are using to describe the long term facilities where they reside. “They are now using terms like, ‘this is a prison,’” she said.

But the precautions are intended to save lives.

“The reality for older adults is that this is a killer,” Orel said. The proof of that was apparent early on when outbreaks hit long-term care facilities hard, resulting in a chain of deaths.

The limits on visitations are focused on keeping the virus out. If a family member were to bring COVID-19 into a facility, the effects could be far reaching.

“As much as you may miss someone,”that’s the worst thing you could do,” Orel said.

Orel knows first hand the heartbreak about having loved ones in a long-term facility during a pandemic. Her parents, both 93, live in an assisted living facility. In their case, window visits were difficult since they live on the second floor. Orel would hold signs outside, but talking was impossible since her parents wear hearing aids and are dependent on reading lips – which masks render useless.

Orel shares concerns about the further isolation cold weather may bring.

“I’m worried about the winter when individuals can’t go outside,” she said.

Seniors at long term facilities face other hardships, such as quarantining in their rooms after being outside for hospital visits.

“They are stuck in their rooms all by themselves,” she said.

Orel suggested families could stay in touch by sending care packages and letters. This older generation grew up writing letters, so they would likely be thrilled to receive hand-written notes and cookies from loved ones, she said.

Outdoor visits – better than nothing

Deb Russell and Sue Lawrence hadn’t seen their mom for months. When they finally did a couple weeks ago, there were masks and plexiglass separating them.

“I live in Bowling Green and haven’t seen my mom since March,” Russell said.

While any visits are good, the sisters struggled to communicate with their mom, Lynn Phillips, 79, who has dementia and is basically non-verbal.

There are limitations to the outdoor visits. For example, at Wood Haven, just two visitors are allowed at once, and they must schedule their visits – so no one can just drop by. Communication can be difficult, with plexiglass separating residents from family, and all of them required to wear masks. Nearby traffic noise at times drowns out conversation.

No touching is allowed – so no hugs, no holding hands.

That is particularly hard for families who have been separated by COVID.

“She wants to hold hands,” Russell said as she tried to communicate with her mom on the other side of the plexiglass.

“You probably thought I forgot about you,” Russell said to her mom.

The sisters tried to make some connection with their mom, and gushed over how nice she looked.

“Your hair looks wonderful,” Russell said.

“You look so pretty,” Lawrence said. “You’ve got your pearls on.”

On the other side of the patio, the same strained visit was going on between Carol Ryland, 89, her daughter Barb Dunn, and her granddaughter Jennie Harriman.

“To me this seems so impersonal, not being able to hug her,” said Harriman, who drove from Fort Wayne, Indiana, to visit her grandma.

They asked Ryland if she slept well, and tried to update her on family members.

But inevitably, the conversation returned to the same issue as Ryland reached out and tried to touch her daughter and granddaughter through the plexiglass.

“I wish I could hug you,” Dunn said.

“It’s awful not being able to hug you,” Harriman said.

Heartbreaking for families

When COVID hit in the spring, long-term care facilities were among the first places to shut down to outsiders. So when Stephanie Rine showed up at Heritage Corner Health Care in Bowling Green to care for her mom, she was met with a locked door.

“There was no communication. I was locked out,” Rine said. “I was just shocked.”

Her mom, Sandra Johnson, 87, was an independent living resident because Rine was her daily caretaker. It was an arrangement that allowed her mom to live in an independent setting, and allowed Rine to be involved in her care.

“I loved that my mom could have her own life there,” Rine said.

Rine hoped to continue that role.

“I had been working from home, sequestering,” she said. “I was really taking it seriously, so I could take care of my mom.”

But that wasn’t permitted. Rine pleaded her case to a state ombudsman, her mom’s physician, Gov. Mike DeWine, and then Ohio Department of Health Director Dr. Amy Acton.

Johnson was deeply distressed, Rine said.

“She would ask me, ‘Why am I being treated like a prisoner? I didn’t do anything wrong,’” Rine said of her mom.

One day, while Rine was in a virtual meeting for work, her mom left five messages on her phone – asking when Rine would be there to visit.

“Every day, it was like I had to break her heart again,” since her mom would forget that Rine wasn’t allowed. “It still is heartbreaking.”

Her mom would often sit by the back door of the facility – waiting for her daughter to arrive, Rine said.

“That’s all she wants is to be with me. I’m all my mom has,” Rine said. “I feel like I fail my mom every day.”

One day when visiting with her mom through her window, Rine noticed her mom was not feeling well. She alerted Heritage, which called an ambulance. Johnson, whose lungs were filling up with fluid, spent two and a half weeks in the hospital.

“I believe her physical decline was lack of care and connection,” Rine said. She has noticed other changes in her mom in the last few months.

“Her dementia has definitely progressed during this,” Rine said.

While Johnson was in the hospital, Rine searched for a home that her family could rent for her mom, or a home that her family could move into that didn’t have so many steps. Her search continues.

Meanwhile, Johnson is back in the facility, but now Rine is allowed to take her mom out for visits in her own home, which she does nearly every day.

Rine continues to advocate for family and senior rights.

“My whole goal was to help everybody in facilities who needs their families,” she said. “People need to see what’s going on with their loved ones.”