By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

The murder of Mary Bach has been a sensation in the county since the crime was committed in 1891.

Generations of residents trooped to the county courthouse and later the county historical museum to view the grisly evidence from the crime – three of Mary’s fingers.

The fingers were severed as her husband, Carl Bach, attacked her with a corn knife. Carl Bach was later convicted and executed by hanging in 1895. He was the last man executed in the county.

Those fingers, as well as a collection of other objects related to the crime, returned to public display at the Wood County Museum in October. Early this month museum curator Holly Kirkendall gave a virtual talk presented by the Wood County Library about how this new exhibit came together and the issues surrounding it.

“People used to go to the courthouse when they were kids and walk through and see the fingers,” she said. “It wasn’t so much about the story, but the simple fact that they were human remains, and humans remains weren’t something you see every day.”

Kirkendall said that when she arrived at the museum in 2012 the “fingers in a jar” were displayed in the government room along with the rope used to hang Carl Bach and an article about the case from the Wood County Sentinel. They’d been moved there about 1978 from the county courthouse.

“It bothered me a little that they were tucked away in a corner,” she said. “There wasn’t a lot of interpretation.”

This, she added, was not a criticism of those who came before her. “Museums and the museum field are constantly evolving. Even what we did 10 years ago, we may say, ‘hey, maybe that wasn’t a good idea.’ … People do the best they can with the tools and resources that they have at the time.”

In 2015, the museum did a renovation including installing an elevator. That meant the fingers exhibit had to be moved.

Kirkendall said staff warned her that people would be upset, but though they received a few calls, most people understood the need to reconsider the exhibit.

Kirkendall had contacted a conservator who would look at the fingers, which were preserved in what was believed to be whiskey. They were rehydrated in a saline solution. The conservator also x-rayed the digits, adding vital information to the story.

Such details, Kirkendall said, help humanize the story.

“It was kind of emotional for me. Here we had this piece of this murdered person that has been in an exhibit case for 100 years. I wanted to take time to consider how are we going to put this back on exhibit.”

Using newly digitized local newspapers, Kirkendall was able to do keyword searches and find more articles beyond the piece written by Charles Evers in the Sentinel.

That piece, an interview with Bach shortly before he was executed, was sensational. One has to question an article in which Mary was described as “dirty” and “slothful.”

A lot of the contemporary coverage was empathetic toward Carl Bach. Mention was made that he had three children. Their mother was dead and their father was soon to be executed. Now they would be orphans. “They were trying to play on the empathy of the community.”

Kirkendall started to think about domestic violence, and reached out to The Cocoon to partner with the presentation.

Museums are concerned about being more relevant. How can they use history and local folklore to connect with contemporary issues and have a positive impact?

The Bachs moved to Wood County around 1869 from what was the Rockport in the Cleveland area. According to the trial transcript, Mary had been married before to a soldier who died at the Battle of Gettysburg. She had a widow’s pension and a house, which she sold to move in with her parents.

The marriage to Carl Bach may well have been more a marriage of convenience, though Kirkendall said as a curator she is careful not to speculate.

Carl had money problems and wanted to sell the land in Wood County, but he needed Mary’s signature. His hope was to use the money to move West. Mary apparently didn’t want to move further from her family.

Carl had “anger issues,” and just a few months before the murder he was jailed for “wife beating.”

Still, Kirkendall said, it’s important as curator to maintain an objectivity and not draw conclusions.

Staff at The Cocoon, though, did say he showed the signs of someone who had issues of domestic abuse.

Kirkendall faced the issue of how graphic to make the description of the murder. Carl struck Mary 15 times in the head with the knife. “I felt there needed to be some understanding about the brutality of her murder.”

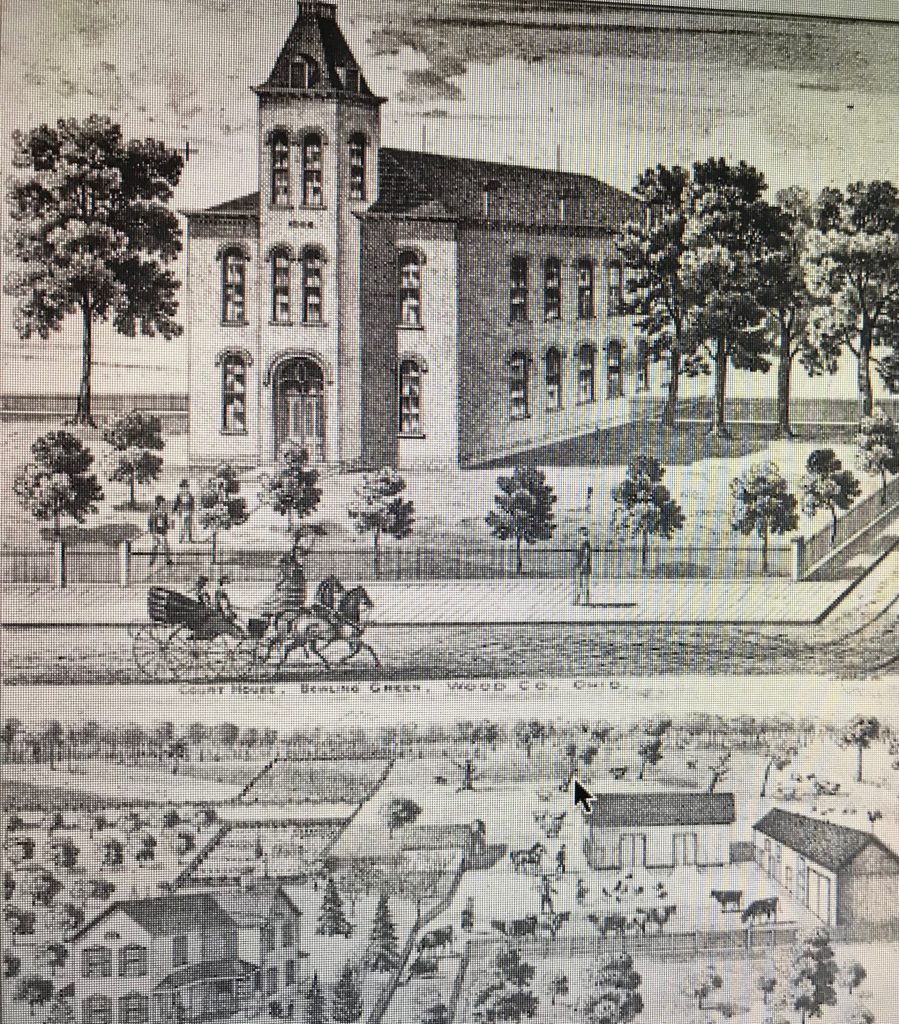

She worked to put the crime in context through an accumulation of detail. There’s a death warrant for Carl Bach. There’s rare image of the courthouse where the execution took place – the second county courthouse, not the current building. She learned the rope used in Bach’s execution was also used in an execution in Henry County. There’s mention of the women who tended to and prepared Mary’s body for burial.

Some people have asked why the fingers couldn’t be buried with Mary’s body. But Kirkendall said her burial site is unknown. And, in any case, that would require the family’s approval.

One woman who said she was a relative came through when the exhibit opened. She “was very happy with the way we portrayed this exhibit,” Kirkendall said.

The children went back to the Cleveland area and lived with Mary’s siblings, and eventually moved out of the area. In her research Kirkendall came upon a granddaughter, also Mary, who moved to Florida and worked at a school for the deaf. “She was really a leader in her field,” Kirkendall said. The pandemic cut short the curator’s research into her life.

Kirkendall said she is interested in picking up the search once life returns to normal. “There still might be more to come. I think there’s more information out there that we’re not getting,” she said. “There’s always something more we can learn from this.”