By KRISTIE FOELL

Special to BG Independent News

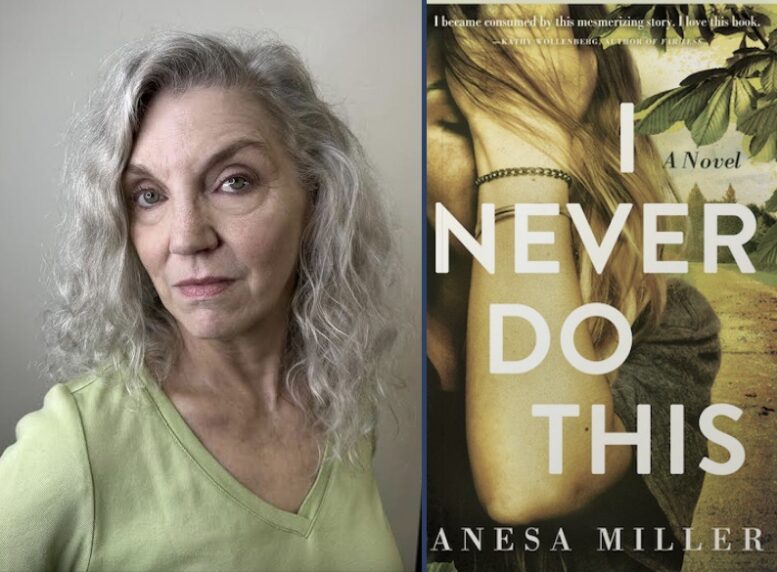

Review of Anesa Miller, “I Never Do This” Sibylline Press 2024. ISBN: 9781960573988

I devoured this novel in two sittings. From the opening scene, the reader wants to know why the narrator “cut Mr. Jonathan Rutherford with a ten-inch folding knife.” But that’s just the frame story, which introduces yet another frame story involving a petty criminal cousin, which enfolds the original one, all to coax out and highlight the novel’s real, main story.

(Anesa Miller will read and discuss “I Never Do This” Sunday, May 19, from 2:30-3:30 p.m. at Gathering Volumes, 196 East South Boundary, Perrysburg.)

Of course, a good novelist is never telling just one story. But for this reader, amidst rich portrayals of life in southern Ohio, family entanglements, social class, gender relations, and the failures of social institutions from church to school to law enforcement, it’s protagonist LaDene’s experience as a pregnant teen that stands out. It’s a timely topic for post-Dobbs America; but even in the America LaDene inhabits, with Roe still in force, she is utterly uninformed and alone. Decisions are made for her, and she is shipped off to have her baby at a sort of reform school. As LaDene travels by bus to her place of captivity, she happens to see a porch light:

“. . . a porchlight somebody might of left on just for me. To light my way. It would be somebody who loved me best in all the world.

“Once upon a time, that was my momma. Now I knew I had nobody like that anywhere.”

The (fictional) New Dawn Ministry for Christian Girls is run with 19th-century discipline occasionally bordering on the medieval. It’s not a “Handmaid’s Tale” dystopia; it’s worse, because these places exist. Masquerading as Christian charity (and accounting for the fact that some of those involved in the endeavor are sincere), the “ministry” is every kind of seedy imaginable. Miller’s keenly-observed send-up of this fictional institution and those who run it is a strength of the novel. Especially noteworthy is a guest speaker from the sheriff’s department, who blames the dangers to young women not on patriarchy, but on their desire for equality: “But let me tell you. Girls get drunk, girls go wherever, go off on their own—they do not get treated fair or equal. Girls get treated way worse—”

The sheriff’s statement is true–women do “get treated way worse”– but even his under-educated teen audience sees through his reasoning that the search for equality itself causes the inequality.

LaDene realizes too late that she could have had a choice, a “do-over,” by getting an abortion. As she reflects on that missed opportunity, she expresses what many of us probably think:

“Truth was, I’d had regrets about that whole abortion question. Since my baby started kicking, of course, I loved her like a real person. … But the honest truth is, I would of aborted her in a second before she started moving, if only it had occurred to me back in Ohio, before it got too late. And I’ve always believed that would of been for the best, in a lot of ways.”

Some of the pro-life persuasion might think that this part of the story has a happy ending: a child is born and placed with a family equipped to provide a good upbringing. LaDene continues her education and, when we meet her, has a job and her own apartment. But LaDene herself is a hollowed-out shell, her former love lost to her, her family barely on speaking terms, her love-life non-existent, and her faith in God destroyed. It takes an outside catalyst (in the form of cousin Bobby Frank) to expose all this, but to find out how that happens, you’ll have to read the book!

From start to finish, this is a midwestern book, set in Ohio and Missouri, with a brief trek through the intervening states. Readers from southern Ohio will relate to the Howell family backstory as ferry operators on the Ohio River, details like “catalpa and mulberry trees,” the use of a native burial ground and a local dam as hangouts, even the omnipresence of meth labs and opioid addiction. But most Midwestern readers will understand in their bones the contradictions around sex education, religious zealotry, and local economic entanglements.

By elevating the voice of a rural, working-class young woman (“ordinary folk,” as LaDene calls her family), Anesa Miller has done a real service not only for literature, but for the American discourse on who is oppressed, who is “deserving,” and which lives and futures and voices count.

For more information: