BY NICK EVANS

Legislation in the Ohio House and Senate would make sweeping changes to the way Ohioans vote and how those votes are counted. Despite sterling post-election audits in Ohio and the arrival last year of strict new photo voter ID requirements, backers insist more must be done to secure the state’s elections.

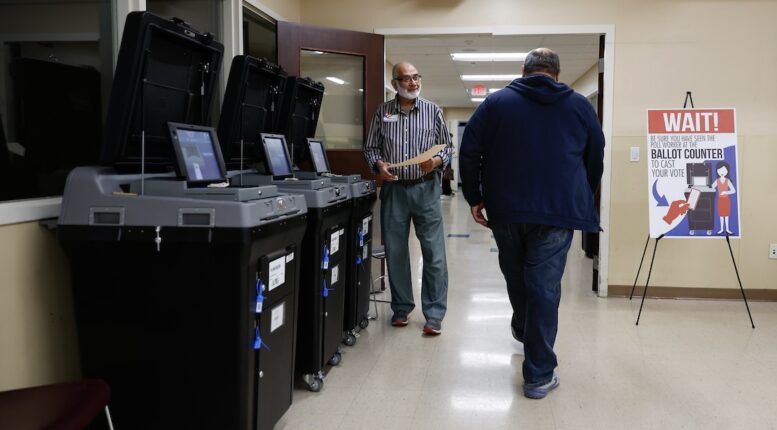

Among their demands are provisions allowing hand-counted ballots, and new voting machine requirements that could force counties across the state to replace the voting machines they have. Moreover, certified voting machines don’t exist that would meet the bill’s standards, and hand-counting has been shown to be more timely and less accurate than the currently certified voting machines that do exist. The bill would also extend photo ID requirements to absentee voting — making voters include a photocopy of their ID with their completed ballot.

And the drafters have plans for in-person voting as well. The bill directs county boards to include a voters’ photograph in the pollbook, so poll workers won’t simply compare a photo ID to person standing in front of them, but also to a photo on file from the Bureau of Motor Vehicles.

[RELATED: Ohio Sec. of State LaRose flagged more than 520 cases of noncitizen voter fraud. Only one was legit]

The League of Women Voters of Ohio policy affairs manager Nazek Hapasha argued the measure is rooted in conspiracy theories about non-citizens voting in Ohio’s elections. Ohio’s secretary of state has referred more than 500 of cases of alleged non-citizen voter fraud since taking office. Only one of those cases led to charges.

“All of this together,” she said, “opens up the door to election deniers to cast doubt over our election systems, and the reliability and integrity of our election system.”

The House version of the proposal, sponsored by state Reps. Bernie Willis, R-Springfield and Bob Peterson, R-Selina, has already had a pair of hearings. The Senate’s bill, sponsored by state Sen. Andrew Brenner, R-Dublin, and Theresa Gavarone, R-Bowling Green, has yet to get a hearing.

In sponsor testimony Willis invoked the growing prevalence of cyberattacks, and Peterson compared the bill’s security measures to keeping your computer’s antivirus software up to date. Gavarone and Brenner struck a similar tone.

“Technology is rapidly evolving, which means that our systems must be constantly updated to prevent bad actors from threatening our elections,” Gavarone said in a press release. Brenner added the bill aims to make Ohio’s elections “as safe and secure as possible.”

You gonna pay for that?

The proposal has garnered push back from elections officials and county commissioners in large part because of the potential expense. In a written statement, the County Commissioners Association of Ohio described the bills as “unnecessary, cumbersome and a huge unfunded mandate on counties.”

State lawmakers earmarked about $115 million for new machines in 2018. According to legislative researchers, it appears none of them meet the standards laid out in the bill.

“So, then that would mean we would need to replace our voting equipment across the state,” Lorain County Board of Elections Director Paul Adams explained. “And that is assuming that we have a vendor that has something certified, as well as a vendor that can supply them in enough quantities.”

In addition to leading the Lorain County board, Adams serves as President of the Ohio Association of Election Officials.

Despite those sweeping changes, Adams noted the bill doesn’t carry an appropriation — “I’ve called it an unfunded mandate in search of a problem” — and even the $115 million lawmakers spent last time didn’t cover the full cost of new machines.

What’s more, the bill’s security standards don’t just cut out the state’s current machines, they’d potentially eliminate all machines. The United States Election Assistance Commission establishes voluntary standards, and the bill requires any Ohio voting machine clear a standard known as VVSG 2.0.

The only problem is the EAC has yet to certify a machine that meets that standard.

Even assuming they did so tomorrow, Adams adds, county boards still wouldn’t be out of the woods.

“Just because somebody goes through certification,” he said, “doesn’t mean that they’ve already started production, and they have enough to replace 88 counties in the state of Ohio.”

Elections officials worry as well about the cost of hand counting ballots. While the bill doesn’t direct counties to count ballots by hand, Adams argued the approach would undermine rather than bolster confidence. He pointed to a mock hand count in Butler County earlier this year.

The county board took a batches of 50 ballots from the March primary and had bipartisan teams tally the votes. On average, it took the teams a little more than 2 hours to tally 50 ballots. Applying that to their precincts, the report estimates “the smallest polling locations could take over 9 hours to count their ballots while the largest locations could take as long as 50 plus hours.” And the authors are quick to note, that’s if everything goes perfectly on the first count. When it comes to cost, the report suggested additional supplies and staffing would set the board back more than $827,000.

The accuracy in hand-counting also worsened. Counting just 150 ballots total, the teams generated 8 mistakes — an error rate of 5.33%. The report noted in the county’s 2020 post-election audit, they went back over 10,600 ballots. The accuracy rate was 100%.

Practical effects

Hapasha worries about how the hand counting and voting machine provisions might interact. Although the measure would “allow” rather than require hand counts, it also effectively mothballs the state’s voting machines.

“And so, practically speaking, if this were to go into effect, it might actually require hand counting the next day even though the bill says that it would only allow hand counting,” she explained.

She also has significant doubts about requiring absentee voters to mail a photocopy of their ID.

“Every elections official that I have spoken to around the state has told me that they have no problem verifying the identity of a person who votes by mail now under the current methods we have,” Hapasha said.

Adams dismissed the idea as well. “How many people have access to a photocopier at home?” he asked. Adams argued the requirement would be particularly challenging for disabled voters, and it could lead to identity theft.

“I think you create more of a reason for fraudulent individuals to target election mail,” he said, “because they know that inside of that is going to be a copy of your driver’s license, which I don’t necessarily think that people want to have out there.”

They both highlighted other provisions in the bill could create substantial delays in getting election results. For one, the bill takes away boards’ ability to pre-process absentee ballots before the polls close. That preliminary work helps Ohio get election night results much faster. For another, if a voter casts an absentee ballot and later votes a provisional ballot, the bill directs the board to count the provisional ballot. That reverses current practice, Adams said, and creates a loophole for voters change their vote.

“This would then encourage organizations and voters to switch their votes if something came up,” Adams said.

With such a sweeping set of policy changes, and less than six months left in the current general assembly, Hapasha argued the lawmakers don’t have enough time to adequately discuss the bill.

“I just don’t see how it’s possible that the legislature could possibly give this bill the time that it needs to go through the legislative process,” Hapasha said. “It makes election administration extraordinarily more difficult, more time consuming, and more expensive, with little to no added benefit.”