By JULIE CARLE

BG Independent News

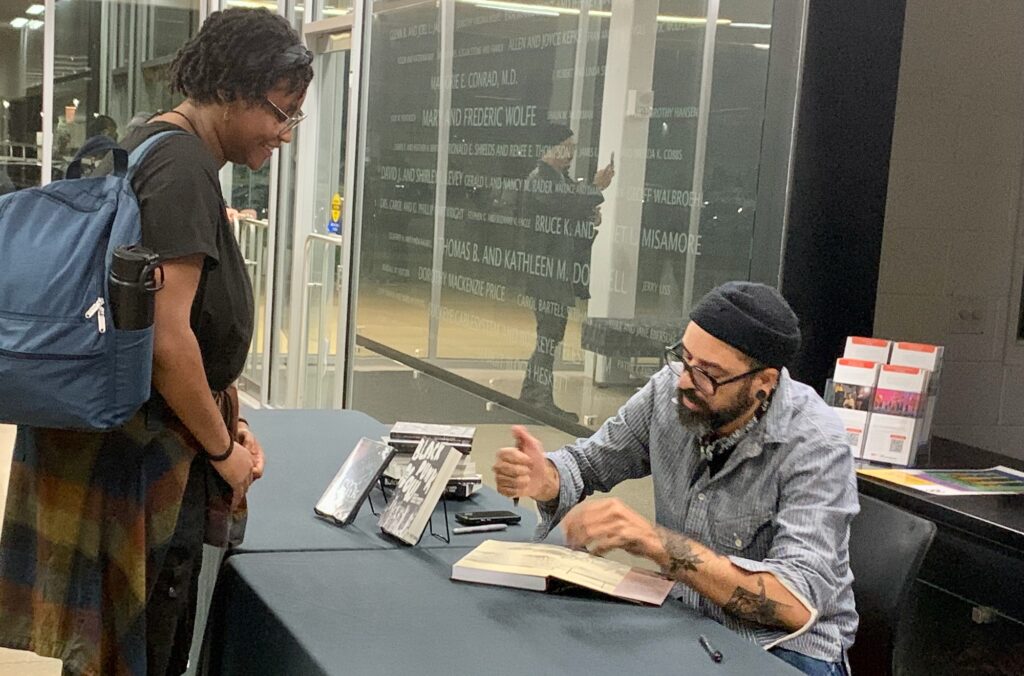

James Spooner, an award-winning graphic novelist, filmmaker and tattoo artist, firmly believes in the ripple effect.

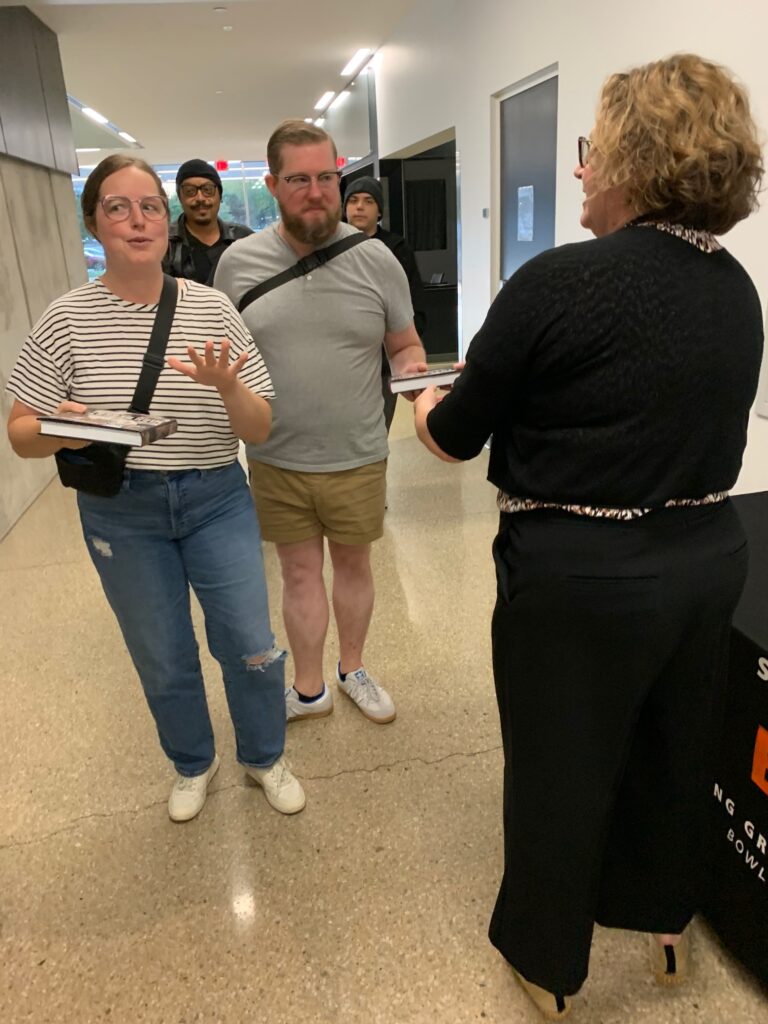

As the speaker for Bowling Green State University’s recent Edwin H. Simmons Creative Minds Series, Spooner talked about his journey that started with the actions of an individual and led to ripple effects of his own.

His story, which is the basis for his graphic novel “The High Desert,” started when he discovered punk rock. He was 13 years old and living in a small desert town two hours from Los Angeles, “where there was nothing remotely edgy or interesting going on,” he said. “The closest thing we had to underground or alternative culture was Hot Topic,” a store specializing in counterculture-related clothing and accessories.

The first day of school he met a Black punk. “He wasn’t perfect, but he set me on a journey that really did bring me here today,” Spooner said. “The small connection I made in the middle of nowhere changed my life. … the beginning of an important ripple effect throughout my life and career.”

Spooner arrived at “the first rule of punk” —DIY—when his friend asked him to join a punk rock band. He had no experience, but hearing the “raw simplicity” of the punk bands, he figured, “I could do that.”

At his first local show, Spooner realized the crowd made it special for him. “For the first time being black felt like an asset. Without knowing anyone in the room, I knew I belonged,” he said. It was there he learned to be Black and punk at the same time.

Because punk “always broke the rules, he realized they didn’t need a record label to finance the band or music lessons to get it perfect. They didn’t adhere to beauty standards, traditional definitions of success or gatekeeping for their art.

“DIY set me down this long trail of creating things in the community and being comfortable about producing art without permission or perfection,” he said. “Punk isn’t just about music, it is political.”

He took on animal rights and feminism in his first zine during high school and started a record label as a way “to contribute to my community,” he said.

Then he decided to “start a movement” — earthwell, to make a difference for the underprivileged.

Young Spooner wasn’t sure his voice mattered. But decades later, he learned how much power he had as an advocate. He had Googled “earthwell” and discovered a group of kids in the Washington, D.C., area started their own earthwell chapter and raised thousands of dollars for domestic abuse survivors and homeless shelters.

He was stunned. He had no idea his earlier had inspired others to get involved. “You might never know how you will affect people, or who you’ve reached,” he said. “That’s OK. It is important just to do the work.”

After high school, Spooner was thinking about the connections he had made with Black punks. As he thought about shared experiences with them, he knew he had to “pay it forward to Black punk” so he created Afro-Punk, a documentary movie about Black Punk.

“It’s not perfect and the production value isn’t great, but I knew that punks would be forgiving,” he said. But when the movie got lots of attention, he started getting calls from universities, film festivals and museums. In three years, the film had been screened more than 300 times.

“I never imagined that something I made for such a small, niche community would resonate so much with others and still be part of the conversation 20 years later, he said.

Spooner also created the Afropunk Festival, a small music festival in the early 2000s for the Black punk community. “By creating the festival, I was doing my part to uphold the culture that held me,” he said.

When 100,000 people in South Africa gathered under the banner of Afropunk, the ripple effect was obvious.

The bigger ripple came after the Afropunk Festival grew and moved away from its punk rock roots. Black punks were left in the margins, he said, but they “picked up where I left off” and started their own music festival that was their DIY.

That was when it hit him. Kids around the country and parts of Europe were connected to the ripple effect of his DIY work from decades earlier. And the ripples continue as their work inspires a new generation.

His graphic novel, which has won several literary awards and is published by mainstream Harper Collins, is having the same kind of impact, on an even larger scale.

As a teen Black punk rocker who learned to take risks, Spooner created lasting impacts through his DIY projects. “I never had success as my goal,” he said. “It’s about community and upholding the culture that cannot be sustained if we stay on the sidelines,” he said. “It’s impossible to measure how much punk has influenced our social and political change that we all benefit from.”