By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

After hiking for months through treacherous cartel controlled lands, they wait on the Mexico side of the Rio Grande. These are the people following the rules, trying to get to the U.S. legally. But they are stuck. They can see American soil, but they can’t get there without breaking the law. So they wait more.

(Editor’s note: This is the first day of a series in Bowling Green Independent News on the human cost to failed immigration policies at the U.S. border with Mexico. This story focuses on asylum seekers wanting to enter the U.S. legally. Joining the Practice Mercy visits to three camps in Mexico were three members of Bowling Green First Presbyterian Church: Pastor Jeff Schooley, O’Leo Lokai and Jan McLaughlin.)

Some leave their homelands to escape violence from gangs. Some migrate due to natural disasters, like the earthquake in Haiti. Some come for jobs, and many come to reunite with family waiting for them in America.

Earlier this month, a group of Americans traveling with the Practice Mercy Foundation, walked across bridges into the Mexican cities of Matamoros, Nuevo Progreso, and Reynosa, the last of which had a Level 4 danger level issued by the U.S. State Department due to high risk of crime and kidnapping.

The Practice Mercy Foundation tasked these church members to be witnesses to the broken immigration system and the humans crushed under its weight.

Why risk the journey

For most, the trek to America is a journey of last resort.

The men are faced with taking a chance bringing their families on the long dangerous journey, or leaving their families behind and sending money home.

Passage through Central America is perilous and daunting.

A study cited in the New York Times found that the rate of sexual assaults of female migrants in the Darien Gap area linking Panama and Colombia has reached numbers normally only seen during wartime.

“By the time they get to the Mexico border, they’ve been to hell and back,” said Alma Ruth, the founder of Practice Mercy Foundation.

At the camp along the Rio Grande in Matamoras, Mexico, a Venezuelan couple who traveled with a baby, cradled in a bundle at their chests, looked lost and exhausted.

“The policies people make in Washington – this is what they produce,” Alma Ruth said, looking at the humans caught up in the inhumane system.

The Venezuelans, who gathered to meet the pastors and their American guests, said their two-month journey was exhausting, and they acknowledged encountering dead bodies along the way. But when asked if they ever considered turning back, none said they contemplated that option.

The Venezuelans said their economy has collapsed, and there are no jobs.

“No wonder people take that journey,” said Pastor Aaron Reyes, who helps with the Practice Mercy mission. “They come to this land to work so they can provide for their families.”

Life on the banks of the Rio Grande

The camps, created by migrants – not the government, were dotted with colorful tarps making temporary homes for families. They had long stretched ropes full of recently washed clothing. Sheets of metal enclosed a small space where people could “shower” using water in large buckets. A few families were lucky enough to find plywood to cover the dirt floors under their tarps.

A short distance away, on the U.S. side of the Rio Grande River, the banks were covered with razor wire, which was strewn with the clothing of migrants who took the chance of crossing illegally.

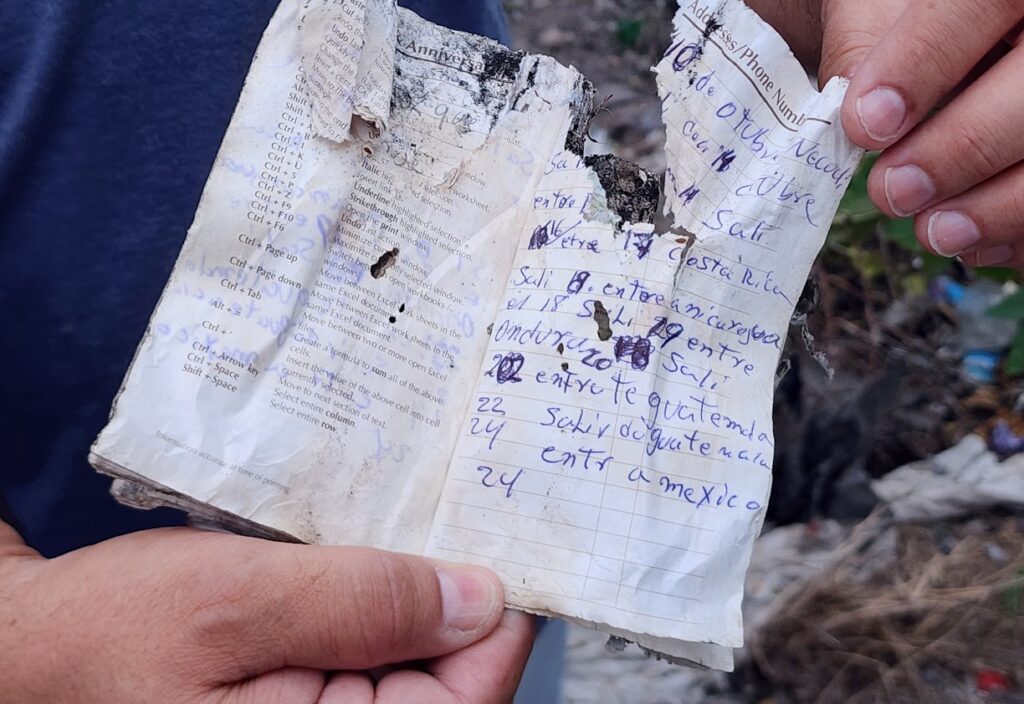

Next to the river were the remnants of a fire, with a partially burned day planner, detailing the journey of an asylum seeker walking from Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico.

In each camp, resourceful refugees had created “kitchens” with an oven molded from mud, and grills over open fires. They proudly showed off their ingenuity to the visitors.

In Matamoros, a young man from Venezuela named Jairo pulled back the tarp to show his kitchen. He shared that he made the mistake one night of not storing his duffle bag of food high enough, and by the next morning, it had all been eaten by rats.

Jairo told the American visitors that he had finally gotten an appointment with immigration authorities. He grinned from ear to ear as he shared his news.

Jairo was worried, however, because he had recently hung his washed clothing on the line to dry, and it was stolen, leaving him with only the ragged clothes on his back. He said he had wanted to look respectful when meeting with border officials.

“All his hopes and dreams are pinned on this country,” said Pastor Jake Clawson, of Trinity Presbyterian Church in Flower Mound, Texas. Clawson knew he would never learn the outcome of the young man’s attempts to come to the U.S.

The adults and children gathered in the center of the camps to politely answer questions from the visitors with varying levels of Spanish speaking skills.

The asylum seekers had next to nothing – but they did have a sense of community. There was no pushing or pleading for the bags held by the church members carrying hygiene items, underwear and socks for the adults, and coloring books with crayons for the children. The asylum seekers quietly waited to see if they would be chosen to receive a bag.

Sense of community in cruel conditions

Despite the living conditions, signs of joy and resilience were seen in the camps.

After crossing the bridge from Hidalgo, Texas, to Reynosa, Mexico, the church members made their way to a camp where about 75 people from Honduras had gathered to wait for their appointments with immigration officials.

When asked where they wanted to go if allowed into the U.S., the Hondurans listed off places where they hoped family or friends would help them get settled – in North Carolina, California, Utah, Arizona, Nebraska, and Columbus, Ohio.

A man named Melvin made the trek to the border by himself, leaving his wife and four children back in Honduras. Rivera said he had an office job in his homeland with Fruit of the Loom, until recently when the company slashed jobs.

Though separated by two months of walking, Rivera kept his family close to his heart, showing church members a photo of his family at a pool.

“Many are trying to protect their children,” Alma Ruth said.

A woman named Azucena told of leaving her homeland eight months ago, and waiting in the camp for six months and 20 days to get an appointment with immigration. She was desperate to get to her 25-year-old son in the U.S., and worried about her two other children left in Honduras.

She continues to wait, though the Rio Grande River beckons.

“It’s tempting, whenever you see the river there, to cross. There’s such a risk,” one woman said. If coyotes see anyone cross without first paying them, the coyotes will kidnap the migrants, she said.

Though the migrants may feel forgotten, they are often being watched from both sides of the border.

While the church members were at the camp in Reynosa, an armed cartel member dressed in camouflage was spotted outside the camp’s gate. Another man dressed all in black acted as a lookout for the cartel from a hill on the edge of the camp. And across the river, a U.S. border patrol agent, also dressed in camouflage in the weeds, could be seen watching the camp.

Alma Ruth said the cartel must feel emboldened because she had never seen members out in daylight.

Comforting those who wait

While in the camp settled by Hondurans, the two American pastors gave words of comfort, where little else could be offered.

“We came to see you and bear witness to your pain,” Clawson said, promising to take their suffering back to his congregation to pray on.

Schooley spoke next to those gathered in the center of the camp.

“Thank you for your hospitality. In the midst of your suffering, your character and kindness glorify God,” he said, assuring them that people of Bowling Green care about their plight. “They’ve heard what is happening and also are despairing.”

Then Schooley asked those in the camp to tell of their dreams, so he could take those hopes home to his church.

One by one, the Hondurans listed their wishes. “I want to cross into the U.S. so I can be with my family,” said one. “I want help so we can keep going,” said another.

“My church will pray for these things,” Schooley said.

After Schooley stopped speaking, several more people sought him out to share their “miracles” privately. A woman wanted to be reunited with her three children in the U.S. A man dreamed of finding work in America. And a young woman told of her sadness since her father died and since being diagnosed with a health issue.

Schooley wrote down each miracle being sought, and each Sunday he adds them to the prayers of his congregation.

Familiar faces still waiting

At another border crossing, between Progreso in Texas, and Nuevo Progreso in Mexico, asylum seekers were crammed onto the sidewalk stretching across the bridge. Many of these were familiar faces to Alma Ruth, who visits the site regularly.

Lately, she has seen a shift from Central American migrants to those seeking refugee status from Russia, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Siberia.

The Russians, who had money to fly from their homeland to Mexico, appeared visibly scared about the possibility of being deported back to their homeland.

Different nations of origin have different waiting periods at the border, Alma Ruth said. Ukrainians are in the “express lane,” while Haitians and indigenous Mayan people are at the bottom.

The Russians waiting on the bridge may have to wait three to four weeks to cross. Haitians have to wait six to eight months just for an appointment with immigration officials, she said.

Background checks delve as deep as possible, said Pastor Ismael Flores, of the Practice Mercy Foundation.

“If you have a mark on your record, you aren’t getting in,” he said. “For the most part, they are just families looking for a better life.”

Creating witnesses

Alma Ruth, a self-professed “Jesus freak,” created the Practice Mercy Foundation in 2019. She was frustrated by the inaccurate portrayal of the people seeking American soil.

So in addition to providing hygiene products to the asylum seekers, Alma Ruth’s organization is focused on providing an authentic view to U.S. citizens.

“I invite people to see immigration through the lens of faith,” she said. “I serve from tent to tent” trying to give migrants hope, along with shampoo, toothpaste, diapers and other necessities.

There aren’t a whole lot of takers for the tours.

“Very few will cross the bridge and serve the refugee camps on the Mexican side,” Alma Ruth said.

Alma Ruth is aware that Mexican authorities, U.S. border control, and cartels know what she is up to. But she also knows that she is safest across the border when she is surrounded by white people.

Alma Ruth wants witnesses to the inhumanity of the U.S. immigration policies. She despises the term “illegals” being used for migrants seeking to cross into America. They are undocumented immigrants – and more importantly, they are humans.

So Alma Ruth takes “gringos” into Mexico whenever possible to see with their own eyes.

“We’re creating witnesses,” she said.