By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

When its first president Homer Williams decided the fledgling Bowling Green Normal College needed an orchestra, it was to boost school spirit by providing music at campus festivities.

The orchestra, all eight members, did a “suitable” job the BeeGee Magazine reported at the time.

On Sunday, that orchestra’s descendant, now 10 times the size, will provide music for its own 100th anniversary celebration.

The Bowling Green Philharmonia with more than 150 voices from the A Cappella Choir, Collegiate Chorale and University Choral Society will perform Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, culminating with the “Ode to Joy,” Sunday, May 5 at 3 p.m. in Kobacker Hall. The program will be repeated the next day, May 6, at 7:30 p.m. in Detroit Orchestra Hall, 3711 Woodward Ave., Detroit.

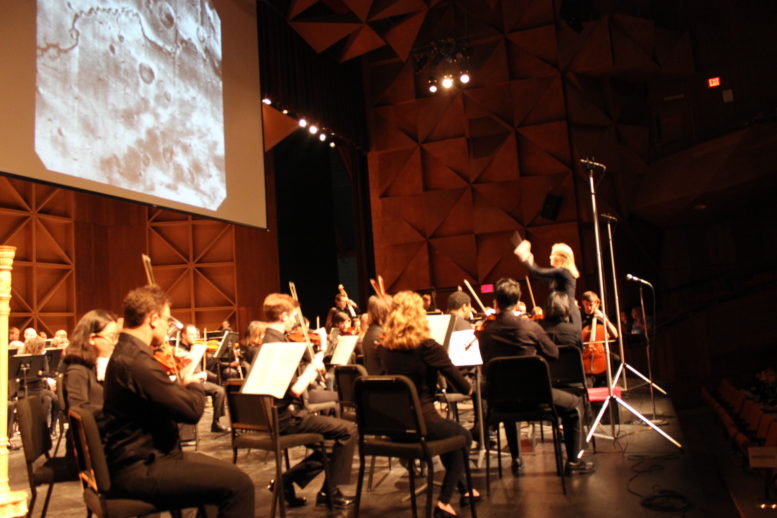

The choice of the symphony, one of the pillars of symphonic music, is fitting, said Emily Freeman Brown, director of orchestral activities.

“The Beethoven Ninth is an iconic work,” she said. “It is a pivotal work that changed what people thought about what an orchestra could do and what the purpose of a concert was.”

The piece has been considered historically significant since its premiere in 1824, a time of dissent and social upheaval.

“It’s Beethoven’s attempt to create a rallying cry about humanity and social justice,” Brown said.

The symphony is often used to commemorate important occasions. That was never more true then when Leonard Bernstein conducted a performance in Germany in December 1989 to celebrate the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The text of the choral movement by poet Friedrich Schiller calls for humanity to come together for the greater good, Brown said. “It appeals to our higher natures.”

Everyone who performs it is changed for the better, she said.

Musically the symphony is brimming with energy.

The piece opens quietly with an uncertainty about what key it’s in, the conductor explained. It exudes “a kind of nakedness, this raw energy. It’s so quiet, so tense. It’s almost like walking in the dark.”

Then, she said, “the tension breaks forth with this explosive energy when the theme appears for the first time.” But the theme disappears again.

“There’s kind of longing, a desire for resolution that we live through as we hear the piece,” she said “It tells such a big story. “

From the point of view of a teacher, this gives the students a chance to perform “a monumental work that’s usually the purview of a professional orchestra.”

Preparing the Ninth Symphony is demanding. “They have to work really, really hard” she said. “Part of the goal is to create peak experiences where, when you’re done with it, you realize what you did and what you’re capable of. It’s important to challenge the students.”

That’s what Brown has done since she took over the podium in 1989. She has directed the orchestra for longer than any other conductor. She assumed the baton from Robert Spano, who has gone on to achieve international accolades as the conductor of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra.

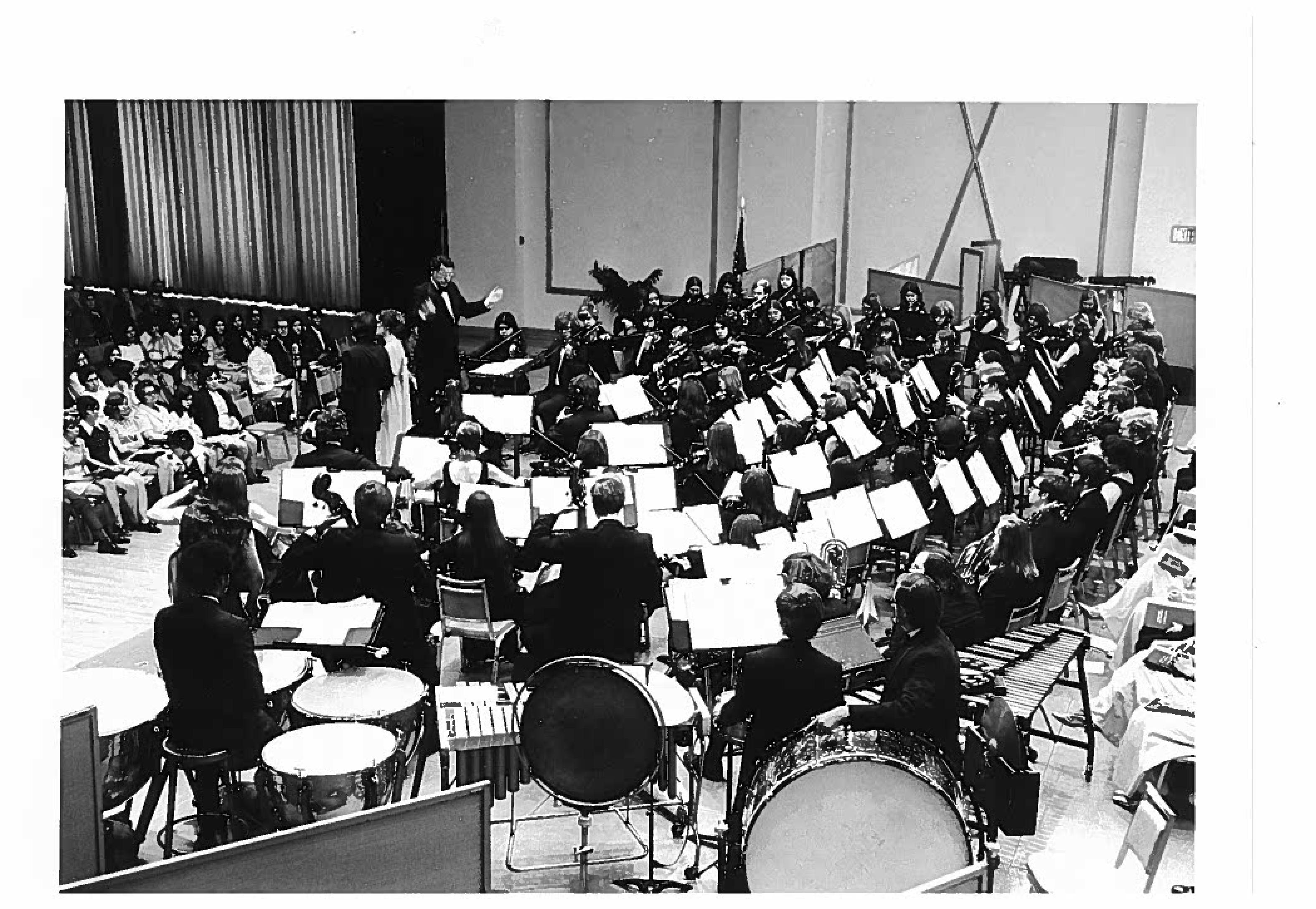

Brown was not the first woman to conduct the orchestra. Two women conducted it during World War II. With so many men in the service, the orchestra was all-female for a time, and had to go on hiatus briefly.

That was not unusual in its first years. It took time for the orchestra to take hold, according to Vincent Corrigan’s book “100 Years of Music at Bowling Green State University.”

That first eight-piece ensemble, seemed to disappear, but by 1924 it re-emerged in larger form. Merrill McEwen, who taught at BGSU before directing the music program, was a central figure in getting the orchestra on its feet.

It wasn’t until after World War II that the orchestra truly found its wings.

Looking back over that history, Brown said, she’s impressed by the consistency of the Philharmonia in quality and mission.

Now with about 80 players, all but a handful undergraduate and graduate music majors, the orchestra performs several times a semester.

Those performances usually include concerts featuring a major piece from the orchestral repertoire. They include performing for fall and spring opera productions.

The orchestra also performs music by contemporary composers during the annual New Music Festival.

That’s given rise to a series of recordings “The Voice of the Composer” on Albany Records, featuring some of those works with commentary by the composers. The eighth volume in the series will be released later this year.

That’s not the only way that BGSU’s place as a center for new music influences the orchestra’s repertoire.

Early each spring semester, the Philharmonia plays with the four winners of the Competitions in Musical Performance.

That poses its own challenges because Brown doesn’t find out until early December when the winners are chosen what the orchestra needs to prepare for a February concert.

Given the focus on new music at BGSU,“it can be really scary.”

She recalls getting off a plane in Detroit after traveling abroad to discover the works that would be performed at the 2017 concert — three very challenging contemporary pieces by Joan Tower, John Corigliano, and Stephen Hartke as well as Maurice Ravel’s Piano Concerto for the left hand.

“I thought I was going to faint,” she said. But “we did it.”

That experience with cutting edge sounds carries over to older repertoire. She said she was struck by how easily orchestra members caught on to the complex rhythms in Igor Stravinsky’s “Petrouchka,” which they performed in December.

Brown said that orchestra alumni often tell her that working with living composers was a high point of their time in the Philharmonia.

Music by a living composer will open Sunday’s concert. Samuel Adler’s “Centennial,” composed for the Cincinnati Orchestra’s 100th anniversary, will serve as a curtain raiser. Throughout the Philharmonia’s centennial season, Brown has programmed a series of such brief celebratory pieces.

The orchestra’s make-up reflects the College of Musical Arts’ student body. “It’s a combination of students who are very interested in becoming music teachers, and students who are very interested in becoming professional orchestra and chamber music musicians,” she said.

And more students now plan to pursue careers in other styles, such as pop, country, and jazz. One current member leads a band of her Philharmonia colleagues.

Most go on to shape careers teaching and performing a variety of styles. That’s typical for musicians, Brown said.

Whatever their career paths, they benefit from the experience of playing in an orchestra. It requires discipline, she said. String players must match bowing styles. Musicians must learn to blend and hear themselves within the symphonic harmonies.

“Learning how to be a good orchestra musician is like learning about how to be a good member of any social group,” Brown said.

On Sunday, a century of imparting those lessons to seven generations of musicians will be celebrated in the best way musicians know how, with a gala performance of arguably greatest symphony ever written.

“We’re still doing what we did before,” Brown said. “We’re still developing the next generation of musicians.”