By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

No sooner had the death of liberal judicial icon Ruth Bader Ginsburg been announced then the speculation on her successor began.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell declared that he wanted the Senate to vote this session on whomever President Trump nominated to fill the empty seat. A departure from his approach when Justice Antonin Scalia died in 2016 when he insisted the Senate wait until after the election.

The political talk blended into the eulogies.

Joshua Boston, a Bowling Green State University professor specializing in judicial politics and law, said he was watching MSNBC and Fox News Friday after learning of Ginsburg’s death. The anchors on both networks, one left leaning and the other right leaning, had similar reactions: “We wouldn’t ordinarily be doing this.”

But, Boston said, when the country is 46 days from a presidential election, “you’re forced into it.”

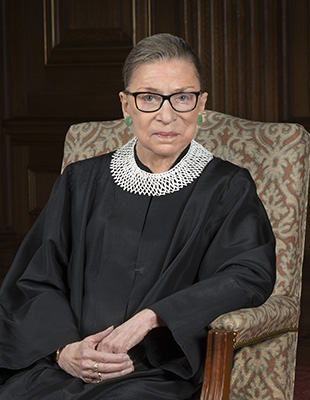

(photo from JoshuaBoston.com)

Boston said Saturday morning he was “still in a state of shock” from Ginsburg’s death. That shock was “irrational” given Ginsburg was 87. She also has been treated for cancer for several years.

This was the same reaction he had when Scalia, who was 79 when he died in February 2016. Given their ages, their deaths shouldn’t have come as a surprise.

Yet both, Boston said, created voids on the court.

For liberals, Ginsburg was known on the court for her opinions on cases that expanded access to employment and education as well as “her impassioned dissents that would later inspire future judges or even inspired legislation,” as was the case with the Lily Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009.

Her work began well before she was appointed to the court in 1993, after having served 13 years on the D.C. Circuit Court, the second most powerful court in the land.

Her life “very much fits with the American Dream,” Boston said. She faced adversity. Her parents died while she was young with her mother dying just before Ginsburg graduated from high school at 15.

Then after excelling at Cornell, Harvard, and Columbia, where she graduated top in her class, she had the doors slammed in her face. Law firms were not interested in hiring a female attorney.

She went on litigate numerous cases on gender equality as an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union.

“As a man,” Boston said, “I cannot fully understand the role she played for women. I can know it and see it on paper.”

To have someone who endured the discrimination stand up in court has an enormous impact, he said. “It means so much to women and other groups historically discriminated against.”

The judge who is considered at the top of Trump’s list of possible nominees is also a woman, Amy Coney Barrett, from the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals.

Trump has made it clear when he nominated Neil Gorsuch to fill the vacancy caused by Scalia’s death, that he was holding Barrett’s nomination for the time when he could fill a vacancy caused by Ginsburg’s departure.

Boston said Barrett “is a reliable conservative” and a devout Catholic who has made her displeasure with the rulings on Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, both landmark decisions affirming a women’s right to terminate a pregnancy, clear

Barrett, he said, “has some interesting takes on precedent and how binding that is on judges,” Boston said. “She takes a looser view of how binding they are. That would seem to open the door to overturning certain precedents on the court that she and other conservatives on the court don’t really like.”

Another name on Trump’s list is Allison Rushing on the Fourth Circuit Court. Rushing is 38, and would be the youngest justice since the beginning of the 20th century. Younger than the 40-year-old William O. Douglas, who ended up being the longest serving justice on the high court.

The court will begin its new term on the first Monday of October with only eight justices.

Boston said the court could hear several cases, though the justices may decide to hold over some until Ginsburg’s successor is confirmed.

Boston is part of a long-term research project looking at how long it takes for judges to be confirmed. In some extremes on lower courts, the seat can be vacant for two years. That’s not the case for the Supreme Court. The process in the U.S. Senate for the Supreme Court usually takes several months.

If the Senate were to act within 40 days before the election, Boston said, some people will be pleased, others angry, but it’s unlikely to damage the legitimacy of the court. “It’ll come out in the wash.”

Research indicates that individual justices don’t impact how the public views the court. That’s true with Brett Kavanaugh who faced a bruising confirmation process. It may be an issue at the time, but then it fades from public consciousness.

“The Supreme Court has a certain amount legitimacy among the mass public,” he said. At a virtual Constitution Day lecture earlier this week, scholar and author Kim Wehle said that the court is not democratic because it is not elected by the people.

Boston disagrees. The Supreme Court is “not inherently democratic” because justices are not accountable at the ballot box. But the Supreme Court is concerned about how the public complies with its opinions. “If the public doesn’t like its decisions, then it loses legitimacy, loses this position of authority.”

While Ginsburg had a well-deserved reputation as a liberal, she was able to work with her fellow justices across the ideological spectrum. Boston noted that 40 percent of the majority opinions she wrote were for cases that were decided unanimously and almost 90 percent were supported by at least six other justices. That’s more than any other justice, Boston said.

“She was very convincing. She was collaborative and collegial.”

While much is made of whether a justice is liberal or conservative those distinctions do not play into the close interactions on the court. “When they work together for a long period, they develop deep relationships even when at odds. That helps to bring clarity to law rather than divisiveness.”

In reviewing court briefs, Boston came across a decision on a case involving punitive damages that was supported by both Ginsburg and Scalia.

The friendship between Ginsburg and Scalia is well known, and it has even been celebrated in an opera.

“To be sure, it was a wonderful friendship,” Boston said. “It is a good example for future justices.”