By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Kimberli Gant, the curator for “Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club,” an exhibit that opened today (June 3) at the Toledo Museum of Art, would like visitors to come away with a new vision of what art can be.

When asked to name five artists, Gant, the Brooklyn Museum’s curator of modern and contemporary art, said at the Friday press preview, that maybe they will include the names of a couple artists they discover in “Black Orpheus.”

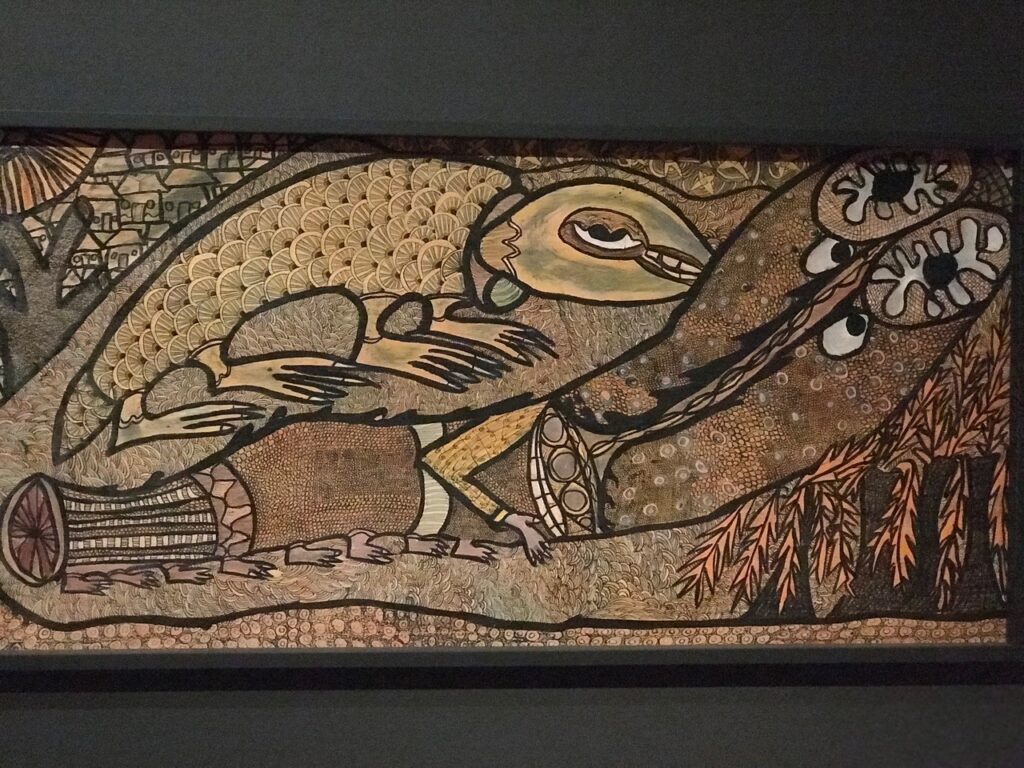

Maybe Twins Seven-Seven, Muraina Oyelami, Duro Ladipo, Asiru Olatunde, Jacob Afolabi or Adebisi Akanji.

These are artists whose bold work is informed by Western art, but inspired and shaped by traditional techniques and iconography.

The connections between this art and that created by African American Jacob Lawrence is striking. At a time when Abstract Expressionism was the style of the day, Lawrence devoted himself to visual narratives depicting the life and history of African-Americans rendered in vibrant colors and geometric designs.

(Abstract Expression was also influenced by African American culture, the sounds of bebop.)

Lawrence is a major figure in modernist art history, museum director Adam Levine said in his remarks. Lawrence’s experience traveling to Nigeria offers a gateway for art lovers to discover his contemporaries who are “too often ignored.”

The exhibit continues through Sept. 3 in the Levis Gallery. Tickets are $10. Click to purchase. It is free to museum members.

Lawrence and his wife, Gwendolyn Knight, were members of the American Society for African Culture. They knew or knew of African artists. At the same time, African artists founded the journal “Black Orpheus” to celebrate both the art of Africa, the diaspora, and artists from round the world working in complementary modes.

While Lawrence’s work came as the battle for civil rights for Black Americans was being waged, the Nigerian artists created in the spirit of newly won independence.

This involved rebelling against the European-based training in colonial institutions.

In 1961 the Mbari Artists and Writers Club was founded.

An exhibit of Lawrence’s work hosted by the Mbari Club brought him to Nigeria for a 10-day visit. And in 1964 he returned with Knight for a longer stay.

Gant said that at the time Lawrence had been labeled a Communist sympathizer. That meant no State Department funding was available to pay for the trip as it was for other cultural exchanges. He and Knight sold their apartment and received help from friends to fund the trip. Also, Lawrence could not get a visa. Through Knight, a native of Barbados, they obtained visas.

Gant first learned of this little-known chapter in the artist’s life while working as a graduate student at the Newark Museum and researching the museum’s catalog. The bits of information she found spurred her to greater research into the whereabouts of the paintings and drawings he made while in Nigeria and exhibited in New York on his return were.

She wanted to present not just those, but the context in which they were created. Gant said she included artists who were featured in the pages of “Black Orpheus” and exhibited by Mbari.

A couple generations of artists have been ignored, Gant said. Only now are those, now elderly, still surviving receiving some recognition.

Fostering this kind of exposure is part of the museum’s mission, Levine said.

The museum is committed to both quality and belonging. “These form the two strands of the double helix of the museum’s mission.

Levine said quality is “egalitarian” and widely distributed. The museum seeks to broaden the view of what is quality art. Few exhibits, he said, reflect the diversity of the global experience as well as “Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club.”

Bringing the show to Toledo, he said, “was a no-brainer.”

After Toledo the show will travel to Virginia and New Orleans.