When it was created in 2013, an Ohio tax break was billed as a way to help small businesses create jobs. But as it approaches its 10th anniversary, the tax break is disproportionately benefiting the wealthy while doing little to deliver on its promise, a new study says.

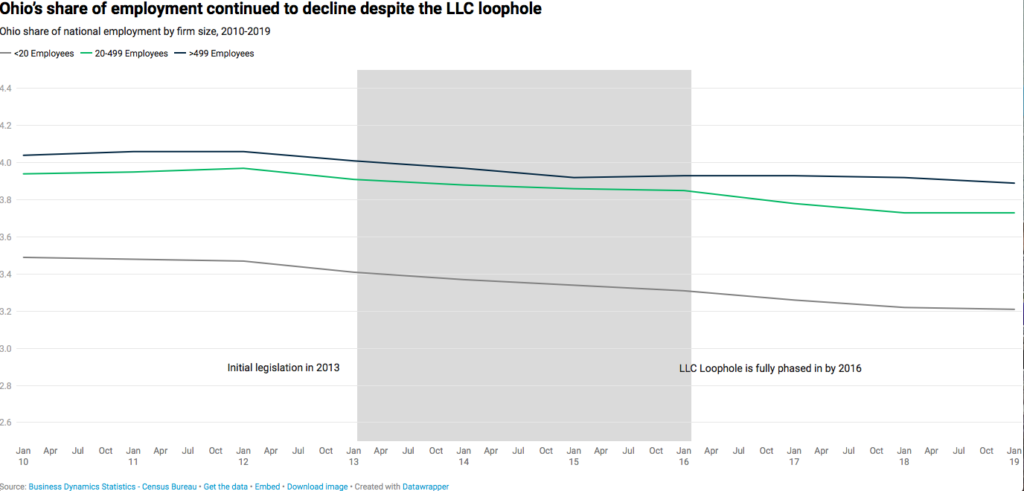

The “pass-through loophole” is now costing Ohioans almost $1 billion a year. Meanwhile, the state’s share of national employment has continued to fall since its creation — especially among small businesses, the report by Policy Matters Ohio said.

The tax break is one of many gambits in which Ohio’s political leaders have sapped billions from the state treasury over the past decade and given the money primarily to wealthy individuals and companies for the ostensible reason of growing the economy.

Yet Ohio continues to struggle according by a variety of measures. U.S. News & World Report ranks the state economy 34th, Quality Counts gave Ohio’s educational system a C-, Ohio had the 15th-highest child poverty rate in 2020 and Cleveland was ranked the poorest large city in the country the same year. In addition, Ohio’s roads — vital infrastructure for doing business — received a grade of “D” last year from the American Society of Civil Engineers.

The Policy Matters analysis finds that Ohio’s pass-through tax break is another expensive bust — especially when it comes to growing small businesses.

For example, Ohio’s share of workers in the smallest businesses, those employing fewer than 20, has declined since the tax break has been in place.

Ohio workers represented 3.47% of that group nationally at the beginning of 2012. That percentage had dropped to 3.21% at the beginning of 2019 — more than five years into the billion-dollar-a-year tax cut, the study said. That amounts to a 7.5% drop.

“The amount most people receive from the (the tax break) isn’t enough to make or break most viable businesses, but it’s extremely costly to the people of Ohio,” Guillermo Bervejillo, the study’s author and a state policy fellow at Policy Matters, said in a written statement. “Budget cuts that started under (former Republican) Gov. John Kasich have taken about $1 billion a year from the local government fund which paves our roads, makes sure our stores and restaurants are clean, and keeps our air and water safe.”

The Ohio tax break applies to so-called “pass-through” entities: some limited-liability companies, S corporations, sole proprietorships, partnerships and the like. The Ohio law exempts the first $250,000 of income from such entities from any taxes, and taxes the rest of annual income at a rate of 3% — a one-quarter break from Ohio’s top income tax rate of 3.99%.

The tax break was sold with arguments that it would allow small businesses to buy equipment, hire extra people and expand. But after it had been up and running for several years, wags around Capital Square were referring to it as the “lawyers and lobbyists loophole” because people in those professions were perfectly situated to take advantage of it.

The Columbus Dispatch in 2017 did its own analysis, which determined that 49% of the people in the legislature that passed — and refuses to repeal — the tax break, appeared to be in positions to take advantage of it. The vast majority refused to answer questions about it.

One took umbrage at even being asked.

“I’m not going to respond to that,” then-Rep. and now State Auditor Keith Faber said. When asked whether he had voted out of self-interest, Faber, who oversaw passage of the cuts as Senate president, said “It’s absurd. It’s a pretty insulting question.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, benefits from the tax break skew heavily toward the wealthy.

The Policy Matters analysis said that the top 7% claiming qualifying business income in 2020 received 39% of the overall value of the tax break, or about $390 million. And that’s not even counting the one-quarter break they received on business income above $250,000, the report said.

The Policy Matters analysis also determined that the loophole is being taken advantage of by shell corporations and entities that can’t even properly be called businesses.

The report cited several studies showing “that more than half of sole proprietorships, about a quarter of partnerships, and about a tenth of S-corps cannot reasonably be categorized as bona fide businesses. Overall, they find that only about 54% of all pass-through entities generate non-negligible income by engaging in ‘businesslike’ activities such as keeping books, paying employees, purchasing inputs, and paying rent or insurance.”

It added that even entities eligible for the tax break that do engage in “businesslike” activities aren’t the type to hire many people.

“Overall, according to (U.S.) Treasury data, 86% of pass-through entities — the vast majority — do not create jobs for anyone other than their owners,” the report said.

A similar experiment was abandoned in an even more conservative state.

Former Kansas Gov. Sam Brownback led the charge in 2012 and 2013 to eliminate pass-through taxes altogether and to slash state income taxes, especially for top earners. The “supply-side” justification was that additional money in the pockets of those who can create jobs will stimulate the economy and improve the fortunes of all.

The economy didn’t benefit much and the state was bankrupted, the Center of Budget and Policy Priorities reports. The Kansas State Legislature was forced to reimpose the pass-through tax in 2017.

Bervejillo, the author of the Policy Matters study, made an ironic point. Sold on promises that it would help everybody, Ohio’s pass-through tax break has helped the few and harmed everybody else.

“Most Ohio lawmakers have signed off on redirecting resources from our communities and into the bank accounts of well-off people who can avail themselves of accounting tricks,” he said. “The beneficiaries of this loophole are disproportionately older, White, men. This giveaway is not just siphoning funds from support services, like schools, public health, or refundable tax credits for working people, it’s expanding inequality.”