By JULIE CARLE

BG Independent News

A team of Bowling Green State University sociologists has become myth busters about divorce in the United States.

Research led by Susan Brown, distinguished sociology professor, and I-Fen Lin, sociology professor, is challenging common beliefs about divorce and establishing new paradigms.

Half of all marriages end in divorce is a myth, said Brown, director of the Center for Family and Demographic Research and co-director of the National Center for Family and Marriage Research.

“Everybody’s heard this one before that you’ve got a 50-50 chance of ending up divorced,” she said during the recent BGSU Science Café held at Juniper Brewing Co. “This is a cumulative probability that requires us to make some assumptions about what’s going to happen to the divorce rate going forward.”

Instead, Brown used “actual data about the stability of marriages that have been formed already” that can be followed forward over time. Marriage data from the 1970s up to 1990 indicate 50-50 is “pretty on point, and they are still in that risk period,” she said. “

However, younger generations who have married in the last 20 years aren’t exhibiting the same rate of divorce in the earliest stages of marriage when risk is at the highest before it starts to decline. Estimates point to 40% to 45%, Brown said.

Myth No. 2 busted

Divorce has always been and ever will be increasing in the United States is Myth No. 2. Historically speaking, the annual rate of divorce has increased dramatically since the beginning of the 20th century, she said.

The period of the 1960s and ‘70s was dubbed “the divorce revolution,” as the numbers skyrocketed. However, the divorce rate peaked In 1979, “and ever since then, they have been tumbling downward on the order of a 30% decline over the past 45 years,” Brown said. “For the past 45 years, divorce has not been increasing, and it has actually been falling down.”

Myth No. 3 debunked

Myth No. 3, that older adults don’t get divorced, is Brown’s personal favorite, in part because it is the foundation of her and Lin’s research for the past 15 years. “It was true in 1970 and still true in 1990 when fewer than 10% of all people getting divorced were over the age of 50,” she said.

By 2010, the picture started to change, but the two sociologists weren’t aware of it until they heard that Al and Tipper Gore were divorcing after 40 years of marriage.

“Who gets divorced after that many years of marriage?” she and Lin asked as they chatted in a hallway after a staff meeting. “Is this just some celebrity phenomenon or is this real?”

Using the census data they were already using to study cohabitation, marital quality, relationship quality and how children fare in different family forms, they delved into the data to examine what was happening.

“We were just stunned to find that divorce was increasing among older adults while the overall trend for the past 45 years has been one of decline in divorce,” Brown said. “It launched us on this research, and it’s a trajectory that we never would have anticipated.”

The “graying of divorce” remains a phenomenon as recent as 2023 with the data showing 40% of people getting divorced are over the age of 50.

Factors driving the graying of divorce

The aging population in the United States is one of the reasons the graying of divorce is happening. Since 1990, the gray divorce rate has doubled.

“More people are going to be getting divorced even if the rate stays the same just because there are more older adults,” Brown explained.

The population at risk is increasingly aging, making the married population older now than it was 30 years ago. Also, people are waiting longer to get married or possibly not getting married at all.

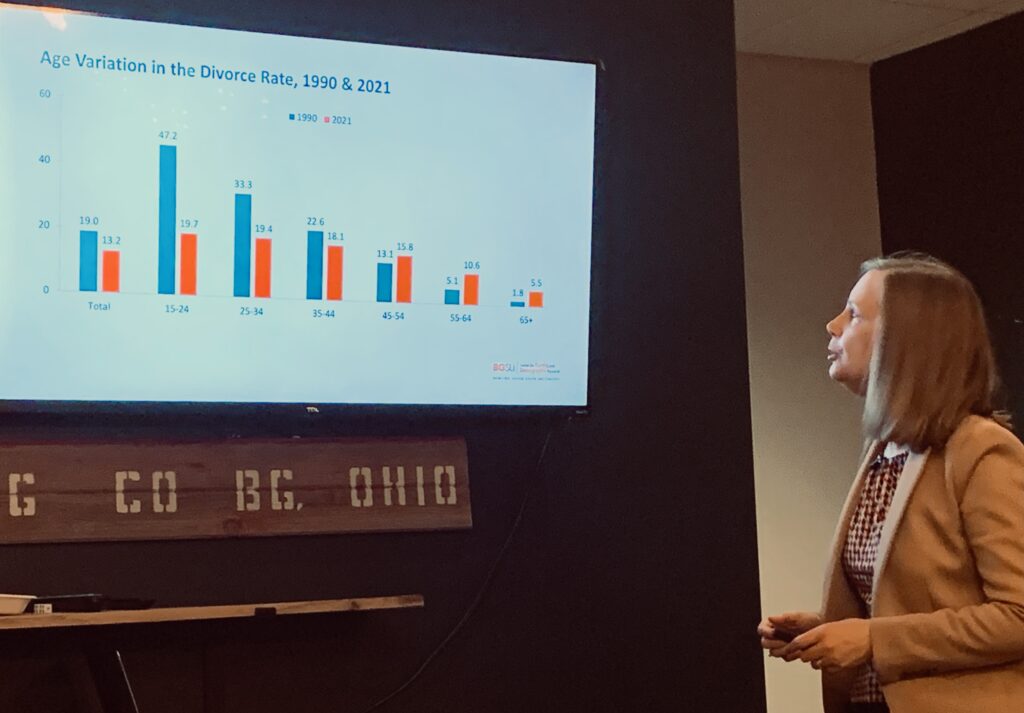

Using 1990 as a benchmark, Brown showed how age variation in the divorce rate has shifted over time. Overall 19 people were divorcing for 1,000 married people, but at that time, the decline in divorce was evident as people got older.

By 2021, the overall divorce rate had dropped to 13 per 1,000. The statistics showed an interesting change: “For young people, there is a sharp decline in the risk of divorce. They are less likely to get divorced today than they were 30 years ago,” Brown said. “In contrast, older adults have seen sharp increases in their risk of divorce, even among people who are 65 and older.”

There is a convergence in the risk of divorce for younger and older adults. “I would argue that the 30% decline in divorce might be more sizable if not for the graying of divorce.”

Divorce today hits differently between young and old

Changing dynamics of marriage are among the reasons divorces have declined among younger generations. Marriage used to be universal. The median age for marriages in 1990 was 26.1 years for men and 23.9 years for women.

“We know that age and marriage are strongly associated with risk for divorce,” she said. “Early marriage is a very big risk factor for divorce, and the longer you wait, the less likely you are to get divorced.”

Today’s younger people are being more selective and waiting until later ages to get married. The median age for first marriages is 30 for men and 28.5 for women.

Far fewer people are choosing to get married, especially compared to the first half of the 20th century. “Since 1970s, first marriages have declined by about 60%,” she said.

There is also a difference based on the level of education. Data from 2023 showed the rate of marriage increased sharply with a post-secondary degree and even more with a graduate degree. “Marriage entry favors people who are more advantaged, economically secure, and are likely to have more stable marriages,” she said. “It used to be people got married at a young age and built their lives together. Now, you’ve got to build your life as a single person to make yourself marriageable.”

Because those milestones can be difficult hurdles for many people to surmount, couples are finding other living arrangements that are viable options now that weren’t acceptable in the past. Today, people can cohabit, live by themselves or live with roommates without the stigma of the past. These factors have also contributed to the sharp decline in divorce for young people.

The shifting dynamic for older adults has increased the divorce rate among people over 50. There was very little change between 1970 and 1990, but by 2010, the rate had doubled from five per 1,000 married people to 10 per 1,000. For the past 15 years, the rate has reduced for adults between 50 and 64 years old.

The story is not the same for adults 65 and older, Brown said. The divorce rate increased starting in about 1990 and continues today.

What’s the difference between the two older adult age groups?

To start, more than 10,000 Baby Boomers are turning 65 every day; they are 17% of the population. By 2050, the percentage of 65 and older adults will be almost 25%.

Generation X, the smaller demographic born between 1965 and 1980, is moving into the 50- to 64-year-old age group. “They are the first generation for whom we saw more of a delay in marriage entry,” Brown said. “More of them are in first marriages and at a lower risk of divorce.”

Baby Boomers came of age in the ’60s and ’70s and were part of the first divorce revolution, she explained. “Many of them got remarried and remarriages are much more likely to end in divorce,” as much as 2.5 times more likely after age 50.

Gray divorce in 1990 primarily affected people in the 50- to 64-year age group. Today, more than one in four people, or 28%, who are getting divorced are 65 years and older.

The trend is “a pretty dramatic shift” that the research attributes to a change in the cultural meaning of marriage and divorce.

“Marriage is no longer ‘Till death do us part.’ Instead, we appraise marriages by ‘What is it doing for me? How happy am I?’” Brown said. “Who you are when you’re 50 is probably not who you were at 25.”

Couples are calling it quits simply because they have drifted apart rather than any precipitating events like adultery. “Marital quality isn’t that different for older adults than it was a generation ago,” she said. “Instead, there’s an unwillingness to stay in what we term ‘empty-shell marriages.’”

Some couples get beyond raising their children and advancing their careers then realize they don’t have as much in common.

The increased life expectancy contributes to the realization that after 65, people may live another 19 to 20 years. “That’s a long time to spend with someone who you’re just not that into anymore,” Brown added.

As women in the workforce have increased in recent decades, they are better able to afford a divorce today more than a generation ago, “when they would have been much more economically dependent on their husbands,” she said.

Consequences of gray divorce

The ramifications of gray divorce go beyond the stress of the experience. While younger people tend to bounce back from divorce emotionally and mentally within a couple of years, gray divorce recovery is more protracted, taking an average of four years.

The financial consequences of gray divorce are much more drastic than for younger divorce.

“What does it mean to get divorced later in life after you have spent in many decades building your nest egg, amassing your wealth only to have to divide it in half?” Brown asked. “Wealth is not something you can rebuild overnight for most people, so this is going to be painful.”

Recovery could take 10 years or more. A 50% decline in wealth with little appreciable recovery “is very sobering when you think about how they are going to navigate old age,” she said.

Though re-partnering is possible, it is not common, which means singlehood will increase and possibly lead to less social support as people become frail and need help.

Because of these changes, “the gray divorce will likely reshape the aging experience in ways that we as a society and our institutions might have to be more responsive toward,” she said. “We have to consider the broader ramifications of what society might need to do to step in and provide additional support.”