By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Marvin Whitfield doesn’t like to be stereotyped.

“As a person of color I don’t like being stereotyped,” Whitfield said. Despite what some people think, African Americans account for only a small percentage of crime in this country.

“As a law enforcement officer, I don’t like to be stereotyped,” he said.

Whitfield, who served in law enforcement for more than two decades before going into private human resources management and training, was part of a panel held at Hull Prairie Middle School in Perrysburg to react to the film “Just Mercy.”

Th movie is a powerful “based on a true story” feature film that explores the dynamics of race and criminal justice.

“Just Mercy” tells of a young lawyer’s efforts in the late 1980s to free a man on Alabama’s death row for a crime he didn’t commit in Alabama.

Walter “Johnny D.” McMillian ran afoul of racial expectations by having an affair with a married white woman. The result was his arrest for the murder of a white teenage girl that was based solely on fabricated evidence by convicted felon.

Whitfield said he was a police officer in Alabama at that time. Also it was during that period the state executed its last prisoner by hanging.

Whitfield wondered if he really wanted to be there.

But he stayed. And he admitted that even as an African-American he picked up racist attitudes about black people as he worked in high crime areas.

If he heard about a case of police misconduct he along with other officers would contend the victim “brought it on himself.”

Then after 26 years, he left law enforcement and started doing research. “I was shocked when I started checking data and found more officers are killed in line of duty by white males.”

Now Whitfield tries to bridge that gap. But it’s not easy. Of 50 community forums he’s been involved with, 47 have ended up with members of the community lecturing the police officers. A recent session in Toledo was “two hours of back and forth … nothing was resolved.”

Efforts to train police to be more culturally sensitive have been equally futile. The officers were lectured to, he said, and if they didn’t have racist attitudes when they went in, they may very well have them when the training was done.

Whitfield found in doing research that there were not data on whether this training was effective. No standards are set for trainers. “Anybody can teach.”

So the problems persist. There’s a lack of accountability, he said. Few officers are ever charged with misconduct. Those with problems are shifted from division to division to avoid being disciplined.

Whitfield said he and “former officers are as shocked as general public” that charges aren’t brought in certain cases such as the death of Eric Garner in New York City in 2014.

Still he sees some progress. More research is being done.

The question remains, he said: “How can we educate the community and law enforcement officers that they are part of the same community, not us and them?”

That requires addressing the past including law enforcement’s role in tracking down runaways during the time of slavery or law enforcement’s involvement in cracking down on Civil Rights protestors in the 1960s as well as recent incidents.

Historian Nicole Jackson tied what happened in the “Just Mercy” to the history of the South. When enslaved people were freed, the white population felt they needed to be controlled, so police forces were created. Under Jim Crow laws — which she noted were modeled on laws used to control free blacks in the North — blacks could only own land if they were sponsored by a white person. If they bucked that system they were considered uncontrollable and ended up in prison.

Prisoners, the Bowling Green State University professor noted, were then rented out to white plantation owners to labor in their fields. Later it was the state and local government that used prison labor to build and maintain roads.

That practice of exploiting prisoners persists, Jackson said.

They are used to fight wild fires in the West. It is dangerous and skilled work. Prisoners die in the line of duty. Yet, when they leave prison, she said, they are forbidden to work as firefighters and use the skills they developed while imprisoned.

Starr Keyes, a professor of education at BGSU, referred to a character in the film who said he was “born guilty.”

“Just him being born as a black male he was just assumed to be guilty,” she said.

Keyes summarized her research into the school-to-prison pipeline.

Stemming from efforts to address violence in schools in the 1990s, ordinary adolescent behavior has been criminalized, Keyes said.

Black students are more likely to get suspended or expelled for behavior such as disobedience and truancy than their white counterparts.

Those exclusionary discipline policies “push students out of the schools and into the criminal justice system and that disproportionately affects racial minorities, students with disabilities, and students in poverty.”

That’s true, not just nationally, but in Northwest Ohio as well, she said.

“You cannot understand criminal justice in this country without understanding the history of race relations,” said Sociologist Steve Demuth, who is on the BGSU faculty. When the Nazis searched for models for their race laws, Demuth said, they looked to the United States. “We have a long history of racial control.”

That’s what underlines the strain of intolerance and polarized politics.

In the 1960s, politics became more polarized. “it’s not just that I disagree with you, but you’re a bad person.” Also, there’s a level of intolerance that equates poverty and crime with sin.

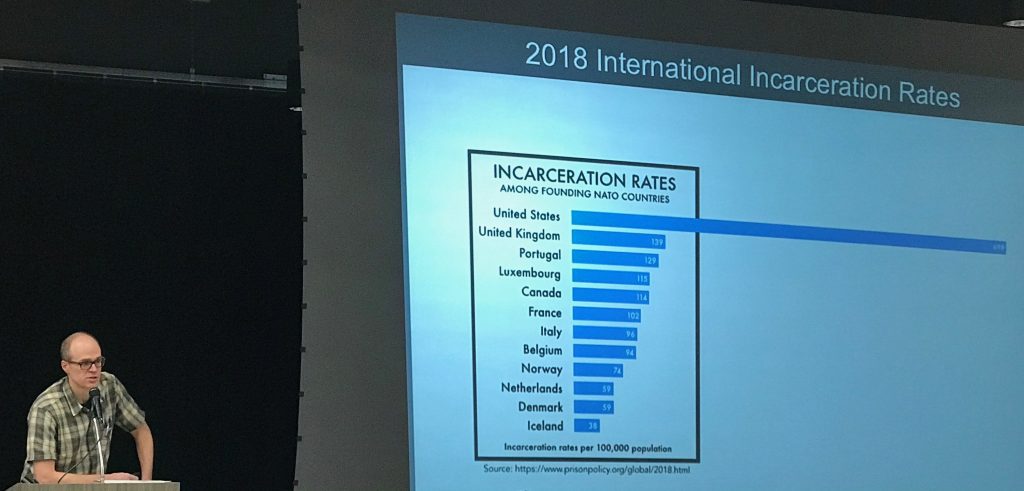

That’s a factor that leads the U.S. to have an incarceration rate, about 700 for every 100,000 people, that is far higher than other counties in the western world —five times greater than the United Kingdom that has the second highest

“It’s unique in the world and unique in history, unless you count slavery,” Demuth said.

That’s not because the United States has more crime. The incidence of most crimes is very similar to other countries. Only the murder rate in the United States exceeds those of other countries.

That, Demuth said, said is “because of access to hand guns. It’s easier for assault to turn into murder with a gun.” There’s little dispute among sociologists about that.

The incarceration rate was flat for much of the 20th century, then shot upward in the 1970s.

Toni Shoola, of the Pretrial Justice Institute, said that much of that increase in people in jail and prison came at a time when crime was decreasing.

More people are being held before they are tried.

In the film, “Just Mercy,” McMillian was held for a year, on death row, before his trial.

“Pretrial is the front door of mass incarceration,” Shoola said.

Ninety percent of the increase in incarceration is from people held before they are tried, she said. In 1983 , a third of all people in prison were being held before trial. In 2016 it was two-thirds.

She pointed to the increased use of monetary bond. This disproportionately affects poor people and racial minorities. African Americans are twice as likely to have to post a monetary bond than non-Hispanic whites and are three and a half times more likely to be jailed before trial.

New Jersey in 2017 instituted a radical reform of the way it handles most arrests, including releasing most people on their own recognizance and almost eliminating monetary bond.

The crime rate, Shoola said, declined.

Demuth said he’s “very optimistic” about the prospect for pre-trial reforms.

In Ohio the American Civil Liberties Union and the Buckeye Institute, “a pretty conservative, libertarian group,” are “collaborating around statutory reform around bail because both of them agree that money shouldn’t have anything to do with liberty.”

People are starting to realize that, he said: “Mass incarceration is going to kill us when we know incarceration causes crime.”

Demuth concluded: “It doesn’t mean you stop locking up people who deserve punishment. But if you do it unnecessarily you are actually creating the problem you are trying to solve.”

Attorney Andrew Mayle said that an overwhelming number of state court judges are former prosecuting attorneys. The effect of that is seen particularly in jury selection, where a prospective juror expressing attitudes favorable to the prosecution is allowed to serve while those with views deemed more favorable to the defense are excluded.

Mayle said the state pension system has incentives for prosecutors, who are public employees, to run for judges because of “they can triple their salary” with the bump in their pensions.

Attorneys in private practice benefit much less from the pension increase.

He also urged people “if you’re called to serve on a jury show up.”

Juries, especially criminal cases which may last days, end up filled with unemployed young people and retirees.

There’s nothing wrong with those folks, Mayle said, but “you want to have a mix of people. Jury service is as important, even more important, than voting.”