By JAN McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

There are places normally privy to just prisoners and maintenance crews at the Wood County Courthouse.

The basement is traversed by inmates headed to and from courtrooms, and by maintenance staff who keep the courthouse in operation. The attic is frequented by staff changing light bulbs above the stained glass ceiling and repairing the courthouse clock that towers over Bowling Green.

But earlier this month, the public was given a chance to explore the non-public places in the courthouse during the Ohio Open Doors program created by the Ohio History Connection to inspire pride in the state’s heritage.

The tours went from the bowels to the belfry of the courthouse.

When the courthouse was completed in 1896 for an estimated $275,000, Bowling Green newspapers referred to it as “the county’s new palatial temple of justice,” “grand beyond any anticipation,” and “as magnificent a piece of architecture as you will ever deserve to see.”

Early visitors marveled at the ornate stone gargoyles, the massive murals, grand staircases, marble from Italy, stained glass vaulted ceiling, and the giant clock tower.

The tours earlier this month touched on those very visible qualities of the courthouse, but they also gave the public a peek at the lesser-known features.

One tour led by Wood County Sheriff Mark Wasylyshyn started with tales of the old jail, sitting right next to the courthouse and currently used as the county’s law library. The jail not only housed prisoners, but also the sheriffs and their families. It was the duty of the sheriff’s wife to cook meals for inmates and care for any female prisoners.

That used to be a perk for county sheriffs – free housing, food and utilities, Wasylyshyn said. But not so much anymore, he added.

The brochure on the historical highlights of the courthouse includes one page of old jailhouse recipes – like baked beans and bread pudding by the wife of Sheriff Ray Coller, and bean soup by Sheriff Earl “Red” Rife.

The grand courthouse, which is recognized by many as an architectural wonder with ornate stonework, has seen more than 120 years of trials, political rallies and people coming in to do everyday business – pay taxes, get marriage licenses, attend public meetings.

Underneath is a maze of basement rooms once used as the county’s emergency command center, and now by county maintenance. The red brick ceilings, arched for strength, and thick stone walls support the courthouse above.

The basement still provides a route for inmates to enter the courthouse without coming in contact with the public until they exit an elevator near the courtrooms.

No longer used is the garage door to the basement, where coal was dumped then shoveled into burners. And equipment from the past lingers, like old radios the likes of those used by Sheriff Andy Griffith.

On the way up to the attic, the tours took a pause in the third floor courtrooms and rooms where juries deliberate. In Courtroom No. 1, Wasylyshyn described how the balcony seating has long since been removed. Before there were TVs in every home, trials were seen as entertainment for spectators, he said.

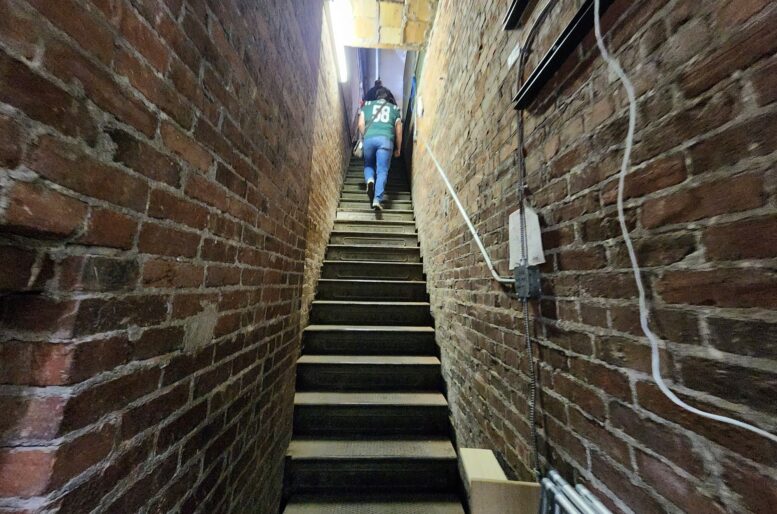

Then it was upward again, to the attic – the home to courthouse holiday decorations and a lot of history. It took some squeezing, but the turrets in front of the courthouse are accessible. It was there that spotters were posted during World War II to keep a lookout for possible German warplanes. Wasylyshyn said there used to be a poster up there identifying German aircraft.

Another climb up a creaky stairs/ladder took visitors to a view of the topside of the stained glass arching the ceiling of the courthouse.

And further up, is the clock tower with its 2,000-pound bell.

When built, the clock tower rising high above Bowling Green boasted clock hands stretching 16 feet – the second largest in America – close behind the 16.5 feet clock hands at the Chronicle newspaper building in San Francisco.

The original clock hands made of basswood, however, soon had to be replaced by metal hands, since pigeons would roost on the wood and mess up the timing. And that just would not do.

“People relied on the clock’s time,” Wasylyshyn said.

The stately building was made from sandstone sent from Amherst, Ohio, granite from Vermont, and marble from Italy. When it came time to connect the courthouse, county office building and old jail with the Alvie Perkins atrium, the county was able to secure sandstone from the same quarry that had previously been closed.

Other stories on the courthouse history and the clock tower can be found at: