(Written by Geoffrey C. Howes, member of the BG Historic Preservation Commission)

For November, the Bowling Green Historic Preservation Commission has chosen several Historic Buildings of the Month that no longer exist: the city’s glass factories. From 1887 to the early 1890s, they represented Bowling Green’s most important industry, which gave it the moniker “Crystal City.”

The oil boom was in full swing around Bowling Green, but within the city limits, glass was king. Why? Because gas was king—at least for a short reign. City leaders, having discovered a seemingly endless supply of natural gas right under their feet, decided to offer gas at no cost to manufacturers who located in Bowling Green.

“THE CRYSTAL CITY. WONDERFUL PROSPERITY, PEACE, PLENTY AND HAPPINESS.” This headline in the Wood County Sentinel on Nov. 24, 1887, celebrated the affluence brought by the glass industry, for which the newspaper thanked natural gas: “That wonderful substance which beautifies our city by night, warms and makes cheerful our homes, has brought here so many manufacturers and gives promise of making this the richest corner of the globe.”

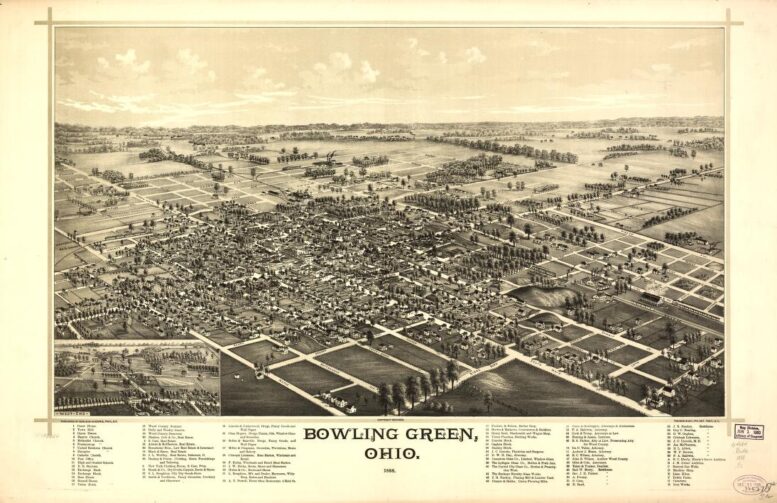

Sand and lime, also needed to make glass, were abundant in the region. The sand came mostly from the Toledo area and there were limestone quarries in and around Bowling Green. An 1888 aerial panoramic map of Bowling Green shows two lime kilns, for processing limestone into quicklime, on both sides of Court Street just east of the tracks, near the current BGSU heating plant and the city fire station. Next to the kilns, at the northwest corner of East Wooster Street and Thurstin Avenue, there was a small stone quarry, now filled in.

The 1888 panorama shows four glass factories. The first and largest, which made window glass, was built by the Canastota Glass Company of Canastota, New York. The company first planned to build in Findlay, but a guarantee of five years of free gas brought it to Bowling Green. The plant was located where Enterprise Square Apartments are now, on North Enterprise Street between East Evers Avenue and East Reed Avenue, later the site of the Heinz ketchup factory.

Northeast of Canastota, the map shows the distinctive octagonal main building of the Lythgoe Glass Company, built over a gas well west of Park Avenue between Frazee Avenue and Poe Road, roughly where the Jordan Family Development Center is now. Started by Charles Lythgoe of Liverpool, England, it was producing bottles and jars by 1887. In 1889, it was reorganized as the Bowling Green Glass Company.

A third factory, the Crystal City Glass Company, was built in 1888 on Manville Avenue at the west end of Third Street, south of Lehman and east of the tracks, near the current Progress Industrial Park. It produced bottles, prescription wares, and canning jars.

The fourth of the original factories was the Buckeye Novelty Glass Company, also built in 1888, southwest of Crystal City Glass, just across the tracks, where apartment buildings now stand on Palmer Avenue. It manufactured screw-necked flasks, flint, crystal and colored glassware, saltshakers, and electric light globes. In 1891, it became Ohio Flint Glass Works.

In 1890, Charles Lythgoe built another plant that made fruit jars just south of the Buckeye Novelty works. John S. Giles was a lawyer-turned-manufacturer who went into the glass business in 1889 when he converted his failed flour mill on North Grove Street (near present-day Crawford’s Lawn and Landscape) into the Safe Glass Company, which made fruit jars, druggist’s wares, and beer bottles. This company is the direct ancestor of the Phoenix Closures packaging company, which still operates in Aurora, Illinois.

On April 19, 1889, the wooden buildings of the Canastota factory went up in flames. The Wood County Sentinel reported: “The Canastota Glass works is in ruins. The pride of Bowling Green, and the pioneer factory, was entirely consumed by the Devouring Element last Friday.” The factory was rebuilt of brick and iron by August 1889, but now as part of the United Glass Company.

Barely a year after that fire, during the early hours of March 18, 1890, the Lythgoe factory also burned down. The Wood County Tribune stated: “The big Bowling Green glass factory, better known as the Lythgoe, is this morning a smouldering [sic] mass of ruins.” Based on information “received on the ground,” the Tribune speculated that the cause was arson, for “there had been trouble with one or two men and threats had been made.” The plant was not rebuilt because the gas well was running dry, which is why one local historian suspects insurance fraud.

Gas, that “wonderful substance,” was running out all over town, and in the early 1890s most of the factories went out of business or moved away. On September 5, 1890, not quite three years after the Sentinel had acclaimed the Crystal City’s new prosperity, a different sort of headline appeared in the Wood County Democrat: “GAS: A TROUBLESOME GOOD.” The paper blasted the gas board for not delivering on its promises. “In the first place there is no such a thing as free gas. Still, when the town was so shortsighted as not to see this, the factories are not to be criticized for endeavoring to hold it to its bargain.”

This was not the end of the glass industry in Bowling Green. In the early 1900s, glass cutting and decorating, as opposed to manufacturing, came to town. In 1901, the Ohio Cut Glass Company set up a plant just south of the old Canastota site. In 1908, Pitkin and Brooks of Chicago took over the plant, which burned down in 1912. From 1925 to 1955, Earl W. Newton, Jr., ran a glass cutting business on Conneaut Avenue, but by then the brief glory days of the Crystal City were long past.

Resources for further study:

Aerial panorama map of Bowling Green in 1888: https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4084b.pm006820/

Joseph Terry, “Bowling Green’s Molten Memories: Stories of Gas and Glass.” Whittle Marks. Voice of the Findlay Antique Bottle Club, June 1999, 1-8.

https://ohiomemory.org/digital/custom/BookReader?manifest=https://ohiomemory.org//digital/iiif-info/p15005coll18/6090/manifest.json

Would you like to nominate a historic building or site for recognition? You can do this through the city website at https://www.bgohio.org/FormCenter/Planning-13/Historic-BuildingSite-Nomination-Form-83

You can learn more about the Historic Preservation Commission by attending the meetings, on the fourth Tuesday of each month at 4 p.m., or by visiting the webpage at https://www.bgohio.org/436/Historic-Preservation-Commission