By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

When it comes to establishing the precedent of sending Americans to fight and die in war without the approval of Congress, the buck stops with Harry S. Truman.

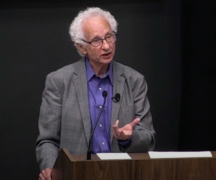

Gary Hess chats with Mary Dudziak before she delivers lecture in the series named in the retired professor’s honor. The Gary R. Hess Lecture in Policy History series was created by his former students.

That was the conclusion of Mary Dudziak, who delivered the Gary R. Hess Lecture in Policy History Monday at Bowling Green State University. Dudziak, a historian and professor of law at Emory University, addressed “The War Powers Pivot: How Congress Lost its Power in Korea,” a chapter from her forthcoming book “Going to War: An American History.”

“I had been a fan of Harry Truman,” Dudziak said. Her first book was on civil rights, and on that score Truman was a hero. His stance was “courageous.” He was “a stronger president on civil rights than FDR and those before him.”

On June 25, 1950, the North Korean Army stormed across the 38th parallel and overwhelmed South Korean forces. “A monster is coming,” was the response of one Korean girl , Dudziak said.

Truman was MIA.

The 38th parallel had been the dividing line between the Communist north and the United States’ ally in the south. That division, the speaker said, was considered the “original sin” for what continues to be a festering international dilemma.

Even as news of the invasion shot across the international dateline, Truman was in Missouri. Instead of rushing back to Washington, he took time to visit his farm and his brother.

The president showed an “unusual amount of deference to the State Department.”

The State Department’s response was to go to the then new United Nations to authorize a military response, and bypass Congress.

The Constitution gives the authority to declare war to Congress, though the president has some authority as president to use military force.

“Korea was the first large scale military operation without a war declaration,” Dudziak said.

It wasn’t even called a war at a time, prompting one mother to ask what she was supposed to put on her son’s tombstone.

It set a precedent that presidents of both parties have used ever since most recently when President Trump ordered air strikes in Syria.

Citing the Constitution’s first words “We the People,” Dudziak said that the neglect of Congress to formally declare war means the people are denied their say in whether members of the military are sent to experience the terror of war.

“Those words are not erased by a powerful president,” she said. “We are ultimately responsible.”

The administration, Dudziak said, did not go to Congress because it feared the vote would not be unanimous. The Congressional opposition to the administration’s approach was led by Senator Robert Taft, R-Ohio, who was seen as a political rival.

The Truman Administration did get authority from the UN Security Council — Soviet Union, which has veto power, was boycotting the council because of a dispute over the status of the People’s Republic of China. The administration believed that the Soviet Union had directed the North Koreans to invade, but later scholars found that it was the Koreans who pushed for the invasion. Soviet documents showed that they “wouldn’t have chosen this as a time to have a big war with the West,” she said.

A number of countries sent troops, including Turkey, but most of the fighting was done by South Koreans and Americans. They paid a terrible price, both from combat and the rigors of the Korean weather. Some soldiers lost limbs to the cold.

Some died because napalm aimed at the North Koreans fell on Americans. This was the first time the chemical agent, which burns the skin from a body, was used.

That kind of suffering makes it all the more important that citizens have a say in whether to go to war, Dudziak said. Yet the country now has a military-civilian divide.

Most commentators date that to the institution of a volunteer military in the wake the Vietnam War. Dudziak thinks it does deeper. Since the beginning of the 20th century all the nation’s wars have been fought abroad. Civilians no longer face the suffering directly. They are no longer part of “the republic of suffering,” to use the phrase coined by Frederick Law Olmsted during the Civil War.

She asked: “What happens to the country when we lose the republic of suffering, when the country can go to war without the civilians being vulnerable to the suffering and death of war?

“It sets us on the trajectory of where we are today,” Dudziak continued. “Some families serve. Some families are deeply tied in to the American experience of war. And other Americans don’t think about it, don’t care about it. And when they go to the polls it’s not part of their decision process.”

She had no answer as to how to get Congress to reassert its authority to declare war.

Deferring to the president has become “historical practice,” and that’s used by courts to help determine what constitutional power is, she said. “The problem is there’s no reset button.”