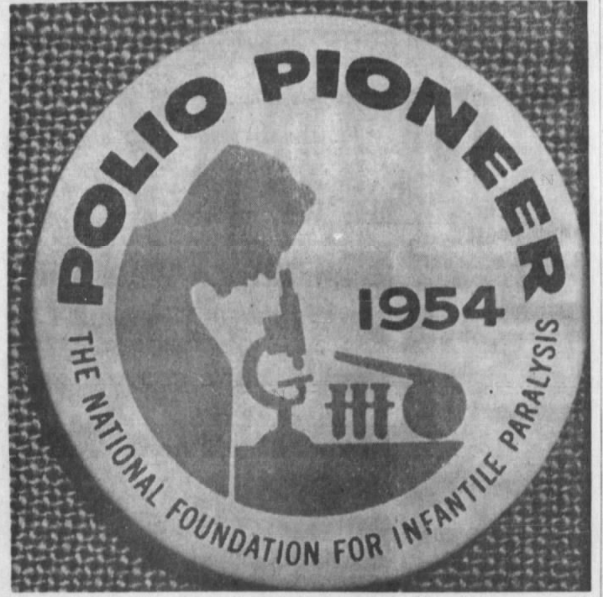

The thousands of “Polio Pioneers” in Ohio, one official said, were short in stature but giants went it came to being medical trailblazers.

These were children in Richland and Montgomery counties who participated in a polio vaccine trial in 1954, with a nation desperate for a breakthrough against a disease that killed thousands and left many paralyzed each year.

In Richland County, around 2,700 children received either the polio vaccine created by Dr. Jonas Salk or a saline solution.

About a year later, readers of the Mansfield News-Journal woke up to see this headline on the front page: POLIO SERUM 100% EFFECTIVE IN COUNTY.

Only four children in the Richland County study ended up contracting polio. All four were found to have taken the placebo.

This was one sample of results from a nationwide test of nearly 2 million children in 44 states, with health experts reporting an overall 80-90% effectiveness for the Salk vaccine.

Around the time the Richland County results were publicized, Oveta Culp Hobby, the U.S. Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, approved the vaccine for national distribution.

Just as they would do with the COVID-19 vaccine 66 years later, Ohio’s health experts got to work educating the general public about the new polio vaccine. More than 1,000 doctors gathered at the Loew’s Theater in Cleveland to watch video on how best to administer the vaccine in their communities.

This was before the days of gubernatorial press conferences broadcast live online and on TV stations. Newspapers carried the heavy lifting in explaining what the vaccine was, what experts said about it and how Ohioans could get it.

Throughout April 1955, outlets such as The Circleville Herald published massive spreads about the vaccine. Its April 12 front page included a bold, all-caps headline: POLIO VACCINE SAFE, POTENT — accompanied by a helpful sidebar Q&A about the vaccine as well as another article outlining the vaccine trial results.

State Health Director Dr. Ralph E. Dwork provided reporters with copious information. A handful of firms manufactured vaccines across the country, with Ohio receiving its supply from the Eli Lilley Co. of Indianapolis and the Wyeth Corporation of Philadelphia. Direct shipments went to Cleveland and Cincinnati, with five other cities serving as regional distribution centers: Columbus, Dayton, Bowling Green, Cuyahoga Falls and Athens.

Dwork noted this distribution system relied on the close cooperation of 227 local health departments. This is almost exactly twice as many local health departments as exist now due to consolidation among city and county departments.

Dayton was an obvious choice in Southwest Ohio, with plenty of supplies left over from the Montgomery County “Polio Pioneer” trial a year before.

Or so the local health officials thought. When they returned to the storage center in April 1955, officials discovered that thousands of needles and syringes were stolen sometime after the trial ended.

“We’ve been paying storage for a year on empty cartons,” a secretary of the local polio response chapter lamented.

Dayton wound up receiving enough supplies that month to get the widespread vaccination program going. This was welcome news in nearby Yellow Springs, where officials vaccinated 152 elementary school children on April 26 — including a second-grade student named Mike DeWine. The future governor was pictured on the front page of the Yellow Spring News two days later wincing while receiving his shot.

The cutline indicates DeWine was in second grade at the time of the photo.

Rebuilding public confidence

In late April, there were reported issues on the west coast with the vaccine supply from one of the five manufacturers. A number of children in California were found to have contracted polio after receiving the vaccine there.

U.S. Surgeon General Leonard Scheele ordered the vaccines from Cutter Laboratories to be withdrawn while health officials could review these cases.

These troubling headlines made Ohio parents worried about vaccinating their children, even though the state’s supply came from separate companies than the one facing scrutiny.

Vaccine hesitancy grew in the months that followed. Some parents refused to schedule vaccine appointments for their kids or had the children skip out on those that were already scheduled.

Dwork blamed on “lack of understanding” of the situation from families.

“Restoring Confidence Is Biggest Polio Need,” read one headline from columnist Peter Edson in early June 1955. Congressional leaders in Washington held hearings about the “Cutter incident” and discussed ways to rebuild trust in the vaccines.

By the summer, the nervousness surrounding the vaccine had dissipated a bit, though health departments had a difficult time organizing a way to get shots out to students while they were at home on break. In response, Dwork organized another major push for vaccinations in August and September when the students returned to school.

Heading into September, an estimated 6 ½ million children across the country had received at least the first shot.

Besides the school vaccinations, Congress approved a federal program to offer free shots at clinics starting in late 1955. It was deemed important throughout the rollout to make sure the vaccination was available for all families regardless of income.

The repeated coverage touting endorsements from Ohio leaders made a big difference.

“Pickaway County residents, after a skeptical start, welcomed the big advanced achieved against polio — in the form of the Salk polio vaccine,” the Circleville Herald wrote around Christmas-time in recapping the previous year. “With the aid of well-organized programs, school children in Circleville and elsewhere throughout the county received the inoculations that may lead the way to a complete defeat for the child-crippling disease.”