By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

As a child in Belarus, Miriam Brysk and her family were rounded up by Nazis and sent to die with other Jews from their city.

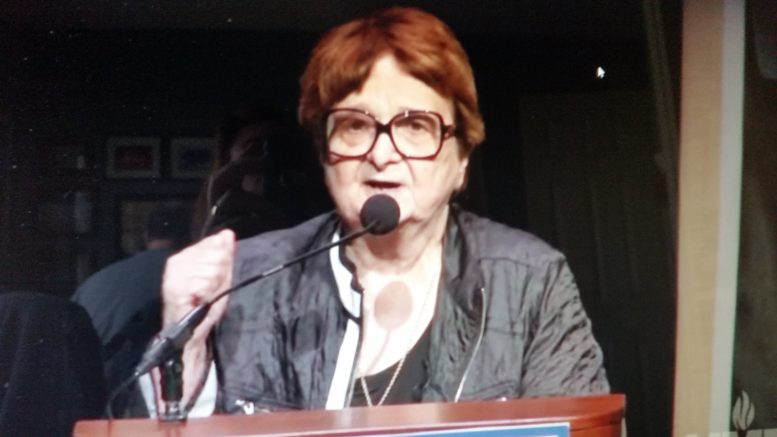

Now, as an 82-year-old in Ann Arbor, Michigan, Brysk said she refuses to sit around drinking tea and playing cards with other women her age. After spending her adult life teaching biochemistry and raising two daughters, Brysk now spends her time reminding people of the horrors of the Holocaust.

“I am doing it in memory of all those who perished,” she said. “I’m preserving their memories. As a survivor, I continue to cry for them. It gives me meaning in my life.”

On Tuesday, Brysk will share her story of survival during a talk at Bowling Green State University, at 7 p.m., in Room 101 of Olscamp Hall.

“I made a pact with God that I would spend the rest of my life making sure the Holocaust would not be forgotten.”

Brysk’s Holocaust story is not the typical experience told by survivors. Her story is not about death camps, but about escaping the Germans to live in resistance camps in the Lipiczanska Forest.

“Most people know about the Holocaust,” she said during a phone interview from her home. “This was a different cup of tea from the regular German holocaust.”

Starting in 1941, Jews rounded up in Russia by the Germans were not sent to camps.

“Not only are they Jews, they are communists,” Brysk said the Germans believed of the Russian Jews. “We can treat them like absolute dogs.”

Many were lined up along ditches and shot. A few would be spared, so they could cover up the graves, she said. “Then they shot them.”

“This went on and on and on,” she said. “I think we knew we were all doomed to die, it was just a question of when and how.”

In May of 1942, Brysk and her parents were sent on a death march.

“The night before, they surrounded the ghetto where we lived,” she said of the Germans. People were forced to leave their homes, and were beat with butts of guns and clubs.

“We were sent to die. We were beaten as we were made to walk,” she said. “We could hear the gunshots. I held onto my parents’ hands as we walked.”

But as they neared the mass grave, a soldier noticed the red cross on Brysk’s father’s sleeve – indicating he was a surgeon.

“They were desperate to have doctors to take care of soldiers,” she said.

The soldier told her father to turn around go back.

“My mother and I looked at each other. Did they mean only him?” Brysk said they were thinking. The German soldier let them all return to the Lida ghetto. “They made us bow down to them” to show how grateful they were for their lives. “It was a pitiful sight.”

Her father was forced to care for German soldiers.

“He was closely watched of course while he operated,” she said.

Later that summer, when rumors circulated that all Jewish children would be killed, Brysk was given to a Christian woman. She returned to her parents in the ghetto a few months later. But chances of survival in the ghetto were getting worse, with many dying of starvation and diseases.

So Brysk and her parents escaped to the Lipiczanska Forest, where resistance fighters had gathered to make strikes on the Germans.

“We wanted to go to the forest and fight,” she said. “The wildest forests of all were in Belarus. The Germans had a hard time navigating them.”

Life there was not any easier.

The family lived in a ziemianka, an enclosure dug into the earth. Brysk’s father continued to use his medical skills as one of just a few doctors in a forest hospital tending to those in the resistance. But that meant her father would be away for weeks at a time. Fearing that Brysk would be a victim of rape, her parents shaved her head and made her wear boy’s clothing.

The winters were brutal and there were several close calls with German soldiers searching for the resistance fighters. Brysk recalled one instance when she and her mother heard German voices. They hid, hoping the soldiers didn’t have dogs.

“They passed right by us and didn’t know we were there.”

“I may not have understood the politics, but I knew when to keep quiet,” she said.

Brysk’s mother became sick and unconscious for days from Typhus which was spread by lice. “We were covered by lice,” she said.

In 1944, the Russian soldiers liberated those in the forest. “We were assigned to live in a certain town. The communists ran a pretty strict regime, too. It was no place to live. I got sick with one childhood disease after another.” The Soviets said doctors were not allowed to travel, but after her father saved the life of one high-ranked soldier, Brysk and her family were smuggled out in the bed of a truck.

They went to Poland, where even after the war ended in 1945, “the anti-Semitism was still rampant,” she said. The family bought its way into Czechoslovakia with a bottle of vodka, then moved to Hungary, then Romania.

“The Russians were reoccupying all of Eastern Europe,” Brysk said.

On Feb. 23, 1947, the family left on a ship from Italy to America. They settled in Brooklyn.

“I had never gone to school before. I didn’t know a word of English,” Brysk said. “I sat there and didn’t understand a thing.”

But Brysk’s determination got her through high school by age 17. By age 20, she had earned her first college degree. She married Henry Brysk, a Holocaust survivor from France, who was a physicist and professor. They had two children.

But Brysk wanted more. “I wanted to be a scientist more than anything.” Again, she found resistance. When taking the last course needed to complete her master’s degree, she was informed by the professor that he planned to fail her.

“Women don’t belong in science,” he told her.

She went on to get her doctorate in biological sciences from Columbia University. She became a scientist and professor in dermatology, biochemistry and microbiology at the University of Texas, publishing some 85 scientific research manuscripts.

But still, Brysk wanted more. When she toured the death camps of Europe, her life took another turn. “I cried my way through that whole trip,” she said.

She started writing and creating art about the horrors of the Holocaust. She stands strong in her defense of Israel.

“I believe in Israel’s survival no matter what,” she said. “Jews, after 2,000 years, having a homeland means a lot.”

She is not apologetic about her strong feelings.

“I have gone through a tremendous amount of pain, going through the Jewish holocaust. I’m not ashamed of feeling that way. I want my people to survive. I want them to thrive.”

“I’m a survivor. I don’t apologize for what I feel,” she said mentioning the recent rash of Jewish graves being desecrated in the U.S. “If you don’t fight for things, you may share the same fate as the Jews in Europe. You may think I’m crazy, but I am just worried about the survival of Jews in America.”