By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Irene Butter survived the Holocaust. Now she sees signs that people have forgotten its lessons.

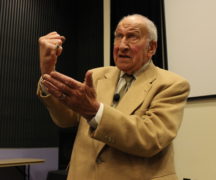

Irene Butter

She sees people being dehumanized, stigmatized because of their nationality, families being broken up and deported. “I see all that happening.” People from the Middle East, Africa, Latin America, and African-Americans are called criminals. “Some people in this country try to get rid of them all,” the 87-year-old Holocaust survivor said Wednesday at Bowling Green State University in a talk sponsored by Hillel. White supremacy is on the rise.

“When Trump says ‘make America great again,’ sometimes it means make America white again,” she said. That echoes the Nazis’ desire to make Germany “clean of Jews because the blood of Jews contaminates the Aryan race.”

That’s what gave rise to the killing machinery of the Holocaust. “I don’t see that,” Butter said. “I see something like the way it all began in Nazi Germany.”

Butter of Ann Arbor, knows well the outcome.

She had a happy childhood in Germany with her parents and her older brothers. If anyone had asked about their identity, they would have said German, first, and then, Jewish. After Hitler took power in 1933, the signs started to appear with the swastika, an ever present symbol of the new regime.

Her brother was beaten up at school and she was ostracized. Then her grandfather’s bank was seized, and her father was out of work. He moved to the Netherlands where he got a job with American Express. Soon the rest of the family joined him in Amsterdam where they lived happily for two and a half years. Then Germany invaded.

Jews had to wear yellow Stars of David. Their movements were restricted. They could only shop after 3 p.m. when few of the scarce rations were left. Even their bicycles were confiscated.

The Jews had to go to segregated schools. They were sad places, Butter said, as there were more and more empty desks. Some because students and their families were able to emigrate from the Netherlands. Others were in hiding. But more because Jews were deported back to Germany and concentration camps.

Butter’s father, through a friend, had applied for Ecuadorian passports. He had heard this may give them other options as “exchange Jews” who could be traded for German citizens held in Allied countries.

Then one day, she said, the Nazis showed up, ordered all Jews out of their homes, told to bring just what they could carry, and marched off to the rail station.

What awaited were cattle cars that would take them to Camp Westerbork. They travel packed into the airless cars with no water, or food, or room to rest. Butter said her family was relatively fortunate they had only an eight-hour ride, others traveled for days in such conditions.

In what Butter described as “a miracle” the family received their Ecuadorian passports at Westerbork before they were transferred to Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany.

The conditions were brutal. People crammed together in barracks. That caused fights and thievery. The adults had to work 12 or more hours a day and were subjected to beatings. The Nazi would force them to stand outside for hours on end in all kinds of weather, so they could be counted.

Butter said she stayed in the barracks to tend to other children. She washed the family’s clothes and stood watch as they hung out to dry otherwise they may be stolen. She collected the family’s scant rations of food.

Her mother became so ill she was confined to her bunk, and Butter cared for her.

Then they were told that those with passports needed to report to be checked by a physician so they could be released. Her mother was too ill to make it, and her father was working. But she and her brother were approved, then her father, injured from a fresh beating, made it, again without being able to bring his wife. But Butter went with him, and the physician checked her father off, and then her mother. Butter wasn’t sure of he was being humane or really thought this young teenage girl was the wife.

The family was put on a Red Cross train on its way to Switzerland where the transfer would happen.

Her father never made it. Two days later he died. He was buried along the way. The mourning family continued on. Her brother and mother were not well enough to leave Switzerland, but Butter was sent to a relocation camp in Algeria. It was heaven. Close to the sea. Freedom to wander. New friends. Still she was not free from the worries about her mother and brother. While she was confident her brother would recover, she was afraid her mother would die.

Eventually the family came to New York City and settled with relatives. Butter pursued her education, eventually getting a doctorate in economics from Duke, the only woman in her class.

But when she first arrived in the Bronx on Christmas Eve, 1945, she was told to forget what she’d gone through, and never talk about it.

It was only in the 1980s when she was participating in an event honoring Anne Frank, who lived in the same Amsterdam neighborhood as Butter and her family, that Butter realized she had a duty to speak.

Anne was not there to tell her story, “so I had to tell her story.”

Now she has written a memoir “Shores Beyond Shores: From Holocaust to Hope, My True Story.” Her story, Butter said, “shows that even after trauma and difficult time, we can get beyond it and still benefit from the wonderful things the world has to offer.”

Butter became an activist. She is part of Zeitouna, group that brings Arab and Jewish women together in the quest to find peace.

Butter said though she loves the founding principles of Israel, and her daughter and her family live there, she disapproves of the current government, and feels the country has betrayed its ideals in its treatment of African refugees and the Palestinians.

The declaration “Never again,” must be backed by action, she said.

Butter told the audience of about 700 that when they see injustice they need to act. That could mean protesting like those in the March for Our Lives movement, or signing petitions, or reaching out to befriend and help those threatened with deportation, and, most importantly, vote.

Asked if she was hopeful, she replied: “It doesn’t look so promising right now. But as someone said to me ‘we can’t give up hope because then there’s nothing left.’ We have to keep hope and do the best we can to work for a better world. It may take many steps, many small steps.”