By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

For the past several years starting with theater productions, events at BGSU would open with a land acknowledgement recognizing the indigenous people who traditionally have occupied Northwest Ohio.

An initiative led by Jenn Stucker, of the School of Art, and Heidi Nees of theater, has taken that acknowledgement further with the In the Round series.

Since early last year, the series has hosted indigenous artists to speak about their work ad their lives. The series was made possible by an award from the Glanz Family Research Award for Interdisciplinary Faculty Innovation and Collaboration.

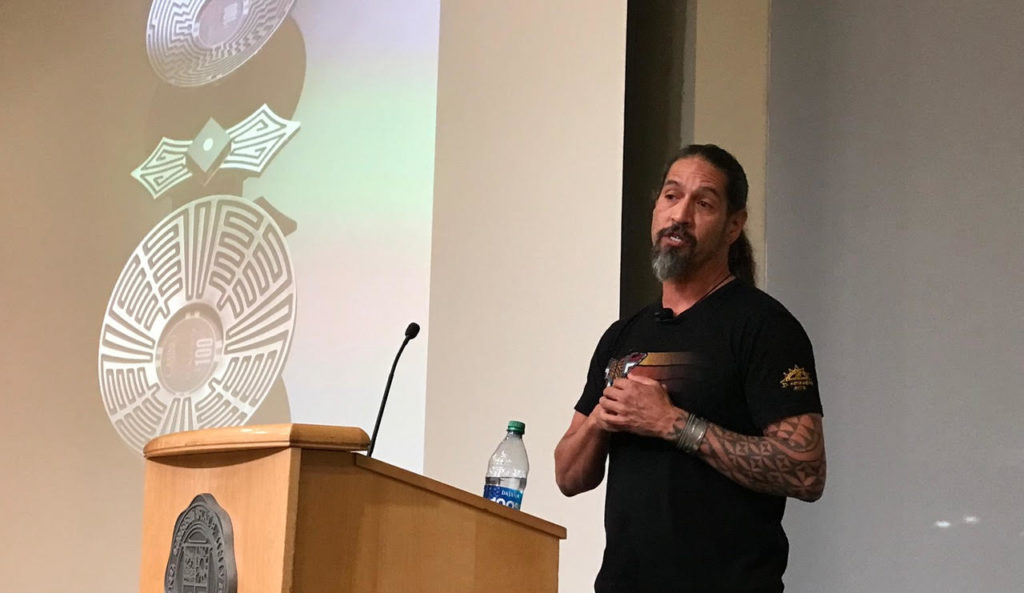

“The series strives to make visible… the artistry, activism and presence of indigenous artists,” said Stucker in her introduction to metalworker Pat Pruitt presentation, the last of the inaugural series of talks held earlier this month.

Tradition meets industry in metalsmith Pat Pruitt’s work

“It’s good to see institutions like this show respect to the cultures that their lands occupy,” Pruitt said.

He noted that his talk was taking place during November, Native American Heritage Month, which was started 22 years ago to recognize and celebrate the diversity of Native American peoples.

He said that it was important especially in an area like Northwest Ohio that has no resident Indigenous population. He lives in the village of Paguate in Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico. “I experience it every day.”

Though Native Americans represent a small percentage of the population, “we’re still here,” he said. “We’re not all the same. … We each come from our own culture. We have our own ceremonies. We each have our own passions.”

His passion is metalsmithing. At 15 Pruitt was seriously injured in a bicycle accident. Bored he took lessons from a metalsmith in his small village. That metalsmith learned the craft from his father who had learned it from his own grandfather.

His teacher’s approach was to teach Pruitt the basics. Then it was up to the student to put his own stamp on the work.

In college where he studied mechanical engineering, Pruitt made jewelry for himself when he got into body piercing. That led to friends asking him to make jewelry for them. Studios approaching him about selling his work.

Through an internship with Texas Instruments, he learned about machining from European trained master technicians. Soon he dropped out of college to start his own business.

While his work in stainless steel, titanium, and zirconium is informed by traditional aesthetics, industrial processes have shaped his style.

Pruitt spent time in BGSU art studios during his visit. Technology, he told students, would further shape their work. In the future, words would become the most important tool. Anything an artist could describe will be realized with digital technology.

Frank Waln taps into the healing power of music

Musician and producer Frank Waln who spoke in October said when he arrived at college in Chicago, he had a classmate who was befuddled by his identity as a Lakota. She assumed, as do so many, that native people were a thing of the past.

That’s not from want of trying by the White establishment.

He grew up on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota. It was a “concentration camp, a death camp where they marched our ancestors to die,” he said. Rosebud is in one of the poorest counties in the country, the schools among the most dangerous. “We were not supposed to survive. We were supposed to die.”

Waln and his people have refused to do that. He started out studying to be a doctor – his own later experiences would show the necessity of having more indigenous medical professionals.

Instead, he turned to another form of healing, music. When he told an elder about his change in careers, the man responded: “Sometimes music is the best medicine.”

Artists create what they and their people need to survive, Waln said.

“Every note is an extension of my heart and my spirit.”

He punctuated his talk with performances of his own music. He performed on flute and voice over recordings that he produced.

His most popular song is “What Makes the Redman Red” which he sampled from a LP of the soundtrack for Disney’s “Peter Pan.”

(Waln said he is an inveterate collector of vinyl and had high praise for BGSU’s Sound Recordings Archives and Finders Music.”)

He recalled his experience moving to Chicago to study audio production at Columbia College. Soon after he arrived, he was riding in a dorm elevator with a young White woman. She admired his hair. He told her “I’m Lakota.” She had never heard the term. A Native American.

She responded: “You guys are still alive?”

He realized that even some educated Americans believed Native Americans were in the past.

“I have to use my gifts to tell my story and be my own true authentic self,” he said.

The oppression of Native Americans is not that far in the past.

The Indian Health Service, which as “wards of the government” Indigenous people still rely on for medical care, inoculated Native youngsters with experimental vaccines without their parents’ permission. Waln remembers getting those immunizations.

Until Indian Religious Freedom Act was passed in 1978, Native religious practices were outlawed. Those found practicing their religion were sent to insane asylums because they worshipped the devil.” This was well within his mother’s life.

When Waln himself had a health crisis and the doctors found scarring on his chest from traditional Ghost Dancing, they mistook it for self-injury and pushed him into psychiatric treatment.

May Katheryn Nagle fights for her people in court & on stage

The interactions between Indigenous People and the law was the focus of another In the Round guest speaker.

A Cherokee playwright and lawyer Mary Katheryn Nagle addressed Native People’s legal struggles to establish sovereignty and how the dehumanizing depiction of Native People in entertainment played a role in that oppression.

She’s asserted Indigenous rights to sovereignty in courts , before Congress, and on the stage.

She noted that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1832 in Worcester v. Georgia that states had no right to impose rules on native land. But neither the state nor President Andrew Jackson enforced the ruling. And in his attempt to remove the Cherokee from his state the governor of Georgia told the state militia to rape native women.

Nagle said that the popularity of the play “Metamora; or the Last of the Wampanoags” on stage at the same time as the Indian Removal was no coincidence. The play featured a White actor, who was also the playwright, in red face, and it contended that he was the last of his tribe, though two bands of Wampanoags still exist and are recognized by the federal government.

The use of red face persists. She pointed the rock musical “Bloody, Bloody Andrew Jackson” that uses white actors portraying Native Americans.

Attacks on Indigenous women has been central to the attacks on Native sovereignty. Native women suffer the highest rates of murder and sexual violence.

In 1978, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled Native courts did not have jurisdiction over non-natives accused of crimes in their jurisdiction.

It wasn’t until a provision in the 2013 Violence Against Women Act remedied that in most of the country – Alaska and Maine were not covered, though they since have been.

Nagle’s play “Sliver of a Full Moon” tells the story of Native women who survived sexual violence.

Yet, Native sovereignty remains under attack.

Earlier this month the Supreme Court heard arguments in Haaland v. Brackeen. The suit involves White families who wish to adopt Native children without following the provisions of the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act, which gives tribes control over the placement of Native children.

That law was passed after about 35 percent of Native children were being adopted or put in foster homes, almost all with non-Native families. This came after the end of the residential school movement which forcibly removed children from their families and placed them in institutions where they were forbidden from speaking their languages and expressing their cultures.

The plaintiffs, including several families and the states of Texas, Indiana, and Louisiana, argued that the law shows racial preference. The government argues being Indigenous is a political identification, not a racial designation, Nagle said.

The In the Round series also brought graphic designer and educator Sadie Red Wing to campus to talk about “Designing for Sovereign Tribal Nations in Higher Education Spaces.

Art exhibit gives voice to Indigenous artists

Also, the University Galleries featured the exhibit “Giving Voice: Native American Prints from Crow’s Shadow Institute of the Arts.”

The 38 works included ranged from the satirical to lyrical. They had reflections on Indigenous history and contemporary life.

Jim Denomie and Larry McNeil use cartoon-like figures to comment on the relationship between Whites and Native Americans. “Shouting Lightning from their Eyes” by John Hitchcock, an artist and musician who gave the closing talk for the exhibit, and speak to the deep links between Indigenous people and the natural world.

Kay Walkingstick’s “Bearpaw Battlefield” is a stark landscape that evokes the tragedy of the last stand of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce.

Contemporary life is vividly depicted by the work of Wendy Red Star. Her print of a truck parade at the annual Crow Fair shows the continuance of horse tradition in new form and employs traditional print patterns that were appropriated by Pendleton Wool.

While Pruitt was the sixth and final In the Round speaker, the series will continue.

On Friday, March 24, the author Kevin Noble Maillard and illustrator Juana Martinez-Neal