By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

Children no longer line up at the chalkboard, practicing elaborate loops for their cursive writing. Most now communicate using their thumbs on tiny keyboards.

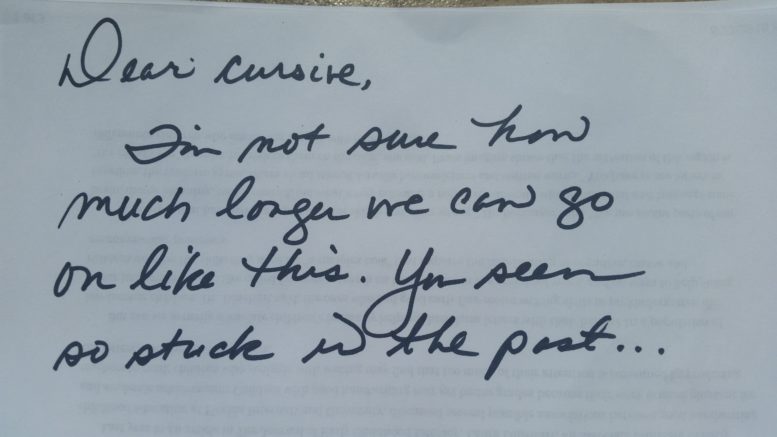

To some youth, cursive writing is as mysterious as hieroglyphics – found only in old documents, in rare love letters, or in unreadable signatures.

Some see this as a natural progression, others as a tragic loss.

“Everything progresses and everything changes,” said Beverly Dennis. “The world is changing and this is where things are going.”

Dennis is stuck somewhere in the middle of the cursive controversy. As a genealogist who works in the Wood County local genealogy office, she sees the value of traditional cursive writing.

“I think the next generations that come along are going to have a lot of difficulty reading cursive,” she said. To a person who appreciates history, that thought is troubling. “If you didn’t know cursive, it would be more difficult to transcribe these old books. There is so much of it in history.”

Plus, there’s a touch of art to cursive writing that just doesn’t exist in typed words. “It’s really beautiful,” Dennis said of cursive with its fancy curves and curls.

However, as a grandmother of teenagers, Dennis sees the natural evolution toward keyboards.

“Cursive writing probably won’t be around long,” she predicted. “Even at my advanced age, I find myself vacillating between cursive and printing. Printing does seem to be easier than cursive.”

Some educators, already feeling pinched for instruction time, see cursive as collateral damage in the fight to get better scores on standardized tests.

Educational standards in most states require teachers to instruct students to write legibly. However, those lessons are usually limited to the earliest primary grades, then replaced by a focus on keyboard skills.

“Any student born after 1981 is a digital student,” said Dr. Ann McCarty, executive director of teaching and learning for Bowling Green City Schools. “And it makes sense for us to focus on things that are a part of their world.”

Schools are often questioned about how youth will learn to write their signatures if they don’t have a grasp of cursive writing. McCarty said that just isn’t a valid reason to dedicate classroom time to cursive.

“How many people’s signatures can you actually read anyway?”

It’s not the schools driving this change, but rather the schools responding to reality.

“I don’t think kids encounter it anymore,” McCarty said. “There’s nothing they get in cursive, except maybe a letter from their grandparents.”

There are two schools of thought, she explained. Some in education believe the tactile motion of writing helps the learning process. Others believe key strokes do the job just as well.

“Everything they do is on devices,” McCarty said of today’s students. “They are starting at a very young age. I don’t see devices going away anytime soon.”

Bowling Green students still learn cursive, though a small fraction of the time spent in the past.

“We don’t teach it to the extent we did 10 years ago,” said Stacey Higgins, second grade teacher at Crim Elementary School. “We don’t try to perfect their strokes.”

Part of the focus shift is due to education requirements that set strict standards. “We just don’t have the time for it that we used to,” Higgins said. “It’s definitely fallen in the priorities.”

Once taught in third grade, cursive writing has been pushed to the second grade level. Higgins still sees the value in teaching the students some cursive, even if they don’t master the skill.

“It’s still a skill that they need,” she said. “It’s a fine motor skill. It’s a life skill. Outside of school it’s important for them to use.”

“They don’t have to master this, but we do want them to be exposed,” Higgins said. “We want them to have both skills.”

Some students find they can write faster with cursive, and can retain more of what they have learned. Some studies have found that students learn better when they take notes by hand, compared to typing on an electronic device.

“There’s a lot of research that says you remember things differently if you write than if you keyboard,” Higgins said.

Oddly enough, though kids seem to gravitate to keyboards nowadays, most enjoy the time spent on cursive, Higgins said.

“The kids are really motivated by it. It makes them feel sophisticated to do cursive.”

Some psychologists and neuroscientists warn that it’s too soon to toss out cursive like it’s an archaic relic.

Those supporting the cursive side of the duel don’t necessarily see technology as a threat and may not be taking a stand to preserve history. Some academics say that it’s actually a matter of science – that children learn better when they write things in cursive. They cite increased brain activation, higher academic performance, and greater coherence and reading comprehensive – with MRIs to back up the claims.

Dr. Susan Peet, a senior lecturer in human development and family studies at Bowling Green State University, sees a reason to expose students to both cursive and keyboarding.

“I think it should not be framed as an either/or question,” Peet said. “Instead, we might spend a little less time on teaching and perfecting cursive writing.”

“I do agree it is diminished,” she said of cursive. “But I’m not ready to say we should throw it away completely.”

Peet compared teaching cursive to teaching students how to read music. “It is a form of language and a form of expression.” While reading music was once standard, it is now viewed as a specialty.

Cutting off cursive as one way of communication just seems a big loss, she added.

“It’s a form of culture. It’s a sign of educated citizenry,” Peet said. And what about translating so many documents of the past – many which were written with fine cursive penmanship? “Who’s going to read the handwritten letters of a generation or two ago?”

At the same time, Peet is realistic about today’s students, their use of technology, and the demands placed on schools.

“The day of spending two hours perfecting the loops in the capital ‘P’ are gone,” she said. “We don’t teach calligraphy anymore either.”

College students are rarely asked to write by hand for any homework – it’s almost completely keyboarding. The departure from handwriting may in some cases lead to less note taking during classes.

“I actually find that students in classes don’t take many notes anymore,” Peet said.

That skill in itself may be a loss in the learning process for students, according to Peet.

“I know how I learn. I still take handwritten notes in meetings,” she said. “There is value in involving another sense” rather than just listening in the learning process.

While electronic devices give students access to more information in far less time, there are disadvantages to having those in the classroom over pen and paper.

“I think they are great,” Peet said of electronic devices. “But the temptations for students are so great to jump over and see what is happening on Facebook.”