By JAN McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

When the shooting began at Kent State on May 4, 1970, Doris Herringshaw was a naïve and studious country girl devoted to her education. John Weslow was a poor but gregarious young man trying to work his way through school. And Richard Sebetto, still a teenager himself, was a member of the Ohio National Guard sent to quell the unrest at Kent State.

When the shooting ended, four students were dead, and the lives of countless others were forever changed.

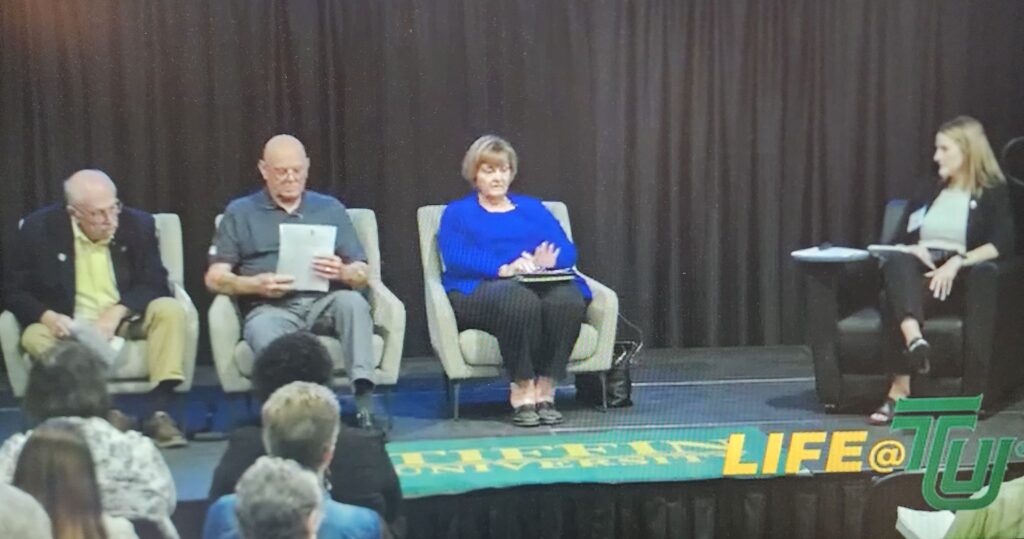

Herringshaw, Sebetto and Weslow, forever linked by the shootings, met recently on a stage at Tiffin University to share their experiences from 54 years ago, and the lasting impact it has had on their lives.

Though they traveled in different circles on campus, Herringshaw, a Wood County commissioner, and Weslow knew each other while at school. Sebetto and Weslow met years later and have forged an unlikely friendship.

An historic recounting of events leading up to May 4, has been attempted by Kent State. It began with President Richard Nixon’s announcement that the U.S. was expanding the Vietnam War by invading Cambodia. Protests occurred the next day, May 1, across U.S. college campuses where anti-war sentiment ran high. At Kent State University, an anti-war rally was held at noon on the Commons, a large grassy area in the middle of campus.

Later that evening, confrontations occurred in downtown Kent between protesters and local police.

The next day, May 2, the mayor asked Gov. James Rhodes to send the Ohio National Guard to Kent. As the Guard members arrived in Kent at about 10 p.m., they encountered more than 1,000 demonstrators surrounding the campus ROTC building which had been set on fire.

On May 3, nearly 1,000 Ohio National Guardsmen occupied the campus, making it appear like a military war zone. Rhodes flew to Kent and issued a statement calling campus protesters the worst type of people in America and stating that every force of law would be used to deal with them.

Rhodes also indicated that he would seek a court order declaring a state of emergency. This was never done, but the widespread assumption among both Guard and university officials was that a state of martial law was being declared in which control of the campus shifted to the Guard rather than university leaders and all rallies were banned.

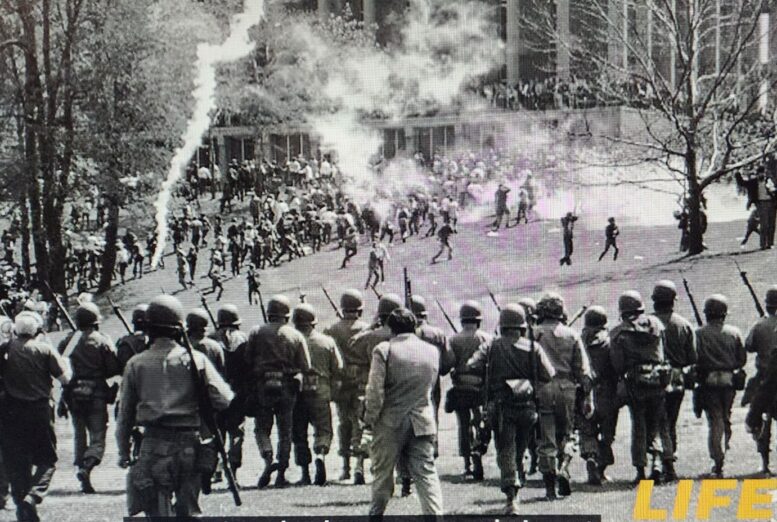

By noon on May 4, the Commons area contained approximately 3,000 people – more than half being spectators. Across the Commons at the burned-out ROTC building stood about 100 Ohio National Guardsmen carrying M-1 military rifles.

Shortly before noon, the Guard ordered demonstrators to disperse. Tear gas canisters were fired into the crowd and the Guard began to march across the Commons to disperse the rally. Faced with yelling and throwing of rocks from the protesters, 28 of the guardsmen fired their rifles.

When the shooting was over, members of the Ohio National Guard had fired approximately 67 rounds over a period of 13 seconds, killing four students and wounding nine others.

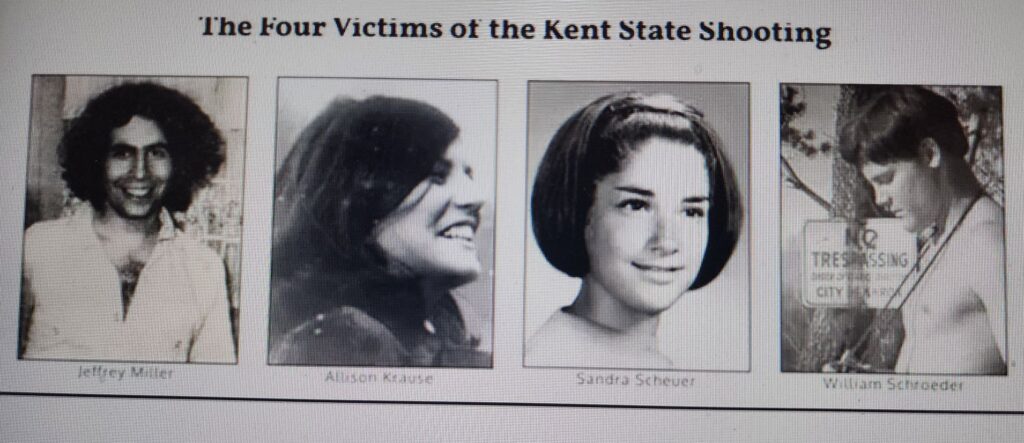

Two of the dead were protesters and two were spectators. The closest student killed was Jeffrey Miller, who was approximately 270 feet from the Guard when he was shot in the mouth. Allison Krause was shot in the left side of her body. William Schroeder, a member of the Kent State ROTC, was shot in the left side of his back. Sandra Scheuer was shot in the left front side of her neck.

Nine Kent State students were wounded, one being permanently paralyzed from the waist down.

Questions still linger about why the Guard fired into a crowd of unarmed students. Some feel the guardsmen fired in self-defense. Others say the guardsmen were not in immediate danger.

The answer offered by many of the guardsmen is that they fired because they were in fear of their lives.

The shootings sent shockwaves on college campuses across the nation, triggering a nationwide student strike that forced hundreds of colleges and universities to close. BGSU became the only major Ohio institution to remain open in the aftermath of the Kent State shootings.

At BGSU, President William Jerome addressed a gathering of 500 students in an emergency meeting four hours after the shootings.

“The next 10 days will tell us more about the destiny of this university than anything that has happened before,” Jerome said from the steps of Williams Hall.

On May 6, an estimated 3,500 students gathered for a rally and teach-in on the BGSU campus. In the evening, students led a candlelit march of more than 7,000 through the town without incident.

The discussion last month at Tiffin University put the three panelists back in the middle of the Kent State campus that May, 54 years ago.

Sebetto recalled coming straight from a teamsters strike in Youngstown to the unrest at Kent. He had no idea what to expect.

“I was flabbergasted. I’d never seen that many students in my life,” he said. Some students put flowers in the guardsmen’s gun barrels, and others spit on them.

“I was a 19-year-old kid with no experience shooting anyone,” Sebetto said.

Herringshaw was not involved in the protests, but it was impossible not to see the military presence and be on edge.

“It was very scary because there were National Guards on the roofs. You could hear the noise, you could smell the teargas,” she said.

The campus was covered with soldiers armed with rifles with bayonets, Jeeps, and armored tank-like vehicles. At night, helicopters with searchlights circled the campus.

Weslow, a less serious student than Herringshaw, recalled sitting on a balcony with friends, trying to finish off a keg, when the helicopters started searching from above.

“It started building,” he said.

An experienced hunter, Weslow said he knew enough to be scared. He saw the types of rifles being carried by the guardsmen, and knew the damage they could cause.

“Everybody didn’t know these were very lethal firearms they had,” he said.

Weslow made sure his shotgun in his apartment was easily accessible.

“I didn’t know what was going on,” he said. “If they come to this door, we’ll take care of them. I was scared.”

On the morning of May 4, he recalled each classroom had a guardsman posted at the door. As Weslow headed back to his apartment, he passed the Commons.

“I saw bloody kids helping each other get out of there,” he said.

Herringshaw had been eating lunch in her dormitory dining area, when a bullet came through the window and into a cement pillar.

Sebetto was at the back of the National Guard troops when they received orders to shoot using live ammunition. Prior to that, they were propelling tear gas canisters into the crowd, with protesters throwing some back at the guardsmen.

“We don’t know who said, ‘fire,’” Sebetto said.

He remembered the confusion of the moment.

“What the hell is going on,” Sebetto remembered thinking. “It was inevitable something was going to take place and it’s going to be bad. The Guard was there and they were loaded for buck.”

When the shooting was over, communication was lacking, with the phone lines being overwhelmed.

“We got our information from the radio. We students were kind of glued to the radio,” Weslow recalled.

Herringshaw’s roommate was a good friend of Allison Kraus. And Weslow was a friend of Bill Schroeder, who he recalled as a model student. Weslow later saw a photograph of Schroeder at the Commons area, holding his textbooks, about 10 minutes before he was killed.

The lives of so many changed that day.

Herringshaw couldn’t reach her family due to poor phone service. In shock, she just knew she had to get home. To this day, she still doesn’t know how she got to the bus station.

“I really don’t remember how I got home,” she said.

“Any of us could have been killed that day,” with stray bullets later found embedded in buildings. “As students, we never thought they were real bullets.”

“I felt kind of stranded, betrayed,” Herringshaw said.

Weslow also went home, and found whatever work possible in hopes of returning to get his degree. He returned for the summer session to a “sense of family” on campus – forever changed.

When Herringshaw returned to Kent, she became much closer with people in her dorm. She became more open to others’ opinions, more able to look at the “big picture,” and more confident to ask questions.

“I was a pretty naive little country girl going to Kent,” she said.

Herringshaw started to question the government, and learn more about the Vietnam War. “I really hadn’t paid much attention to it.” Her husband, Paul, later told her that he went to college so he wouldn’t be sent to Vietnam.

Life also changed for Sebetto.

“Everything stopped,” he said. “We felt as much confusion as anyone.”

The Kent State shootings led to major revisions in how guardsmen were trained for protest situations. Instead of guns, they were armed with batons.

“That’s what we carried from then on,” Sebetto said.

He recalled a buddy in the Guard wearing a tie-dye shirt and wig when they went out, since he didn’t want anyone to know he was a soldier.

“He had it rougher than we did,” Weslow said of Sebetto.

“There were a lot of bad decisions made by people,” Weslow said, haunted by a comment reportedly by Rhodes that he didn’t care if people got shot.

“I started being skeptical of government’s motivations,” he said. He has long questioned reports that students were throwing rocks at the guardsmen.

The three panelists hope the lessons learned on May 4, 1970, are never forgotten.

“Some way, history repeats itself – let’s hope that never ever happens,” Herringshaw said.

Wenslow agreed. “The amount of force used to quell a situation should be equal to the amount of force in the situation.”

And Sebetto stressed that there are now safety valves in place. “We had zero,” he said.