BY NICK EVANS

Two Ohioans and the state Democratic party are challenging a newly devised policy for returning absentee ballots. They argue Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose’s directive requiring people to fill out an attestation when returning someone else’s ballot amounts to making “new requirements and voting restrictions out of whole cloth.”

At the end of July, a federal judge ruled that Ohio’s narrow list of family members legally allowed to return an absentee ballot on behalf of a relative would have to go — at least for disabled voters. Federal law guarantees people with disabilities can get help from anyone they want as long as it’s not their employer or union rep.

The court ruled disabled Ohioans, and only disabled Ohioans, must be allowed to select an assistant of their choice.

Despite that narrow ruling, LaRose urged state lawmakers to think about getting rid of drop boxes altogether.

“I strongly encourage you to consider codifying any additional safeguards that might be necessary due to attempts to erode the integrity of our elections,” he wrote in an Aug. 29 letter, “including possibly banning drop boxes as a result of this court decision which makes it harder to guard against ballot harvesting.”

In the meantime, he issued a directive requiring anyone returning a ballot for someone else to — whether they’re assisting a disabled voter or a family member — sign an attestation verifying that they are complying with state law. That directive is what is now being challenged.

How we got here

The underlying federal case was filed by The League of Women Voters of Ohio and Jennifer Kucera, a disability rights advocate living with muscular dystrophy. League executive director Jen Miller declined to weigh in on the legal arguments laid out in the latest case, but she was unequivocal about the LaRose directive it’s challenging.

“This change is extreme and unnecessary,” Miller said, “and will harm voters of all political stripes in all 88 counties, while making elections harder to administrate for our hardworking elections officials.”

She explained their case sought “a narrow ruling,” and she emphasized when they won that ruling, it didn’t necessitate Ohio officials taking additional steps. They just couldn’t charge “grandkids, roommates and other common-sense helpers” with a felony.

“Our win actually just made Ohio compliant with national voting laws,” she said. “It should not be used as an excuse to place greater burdens on voters or elections officials.”

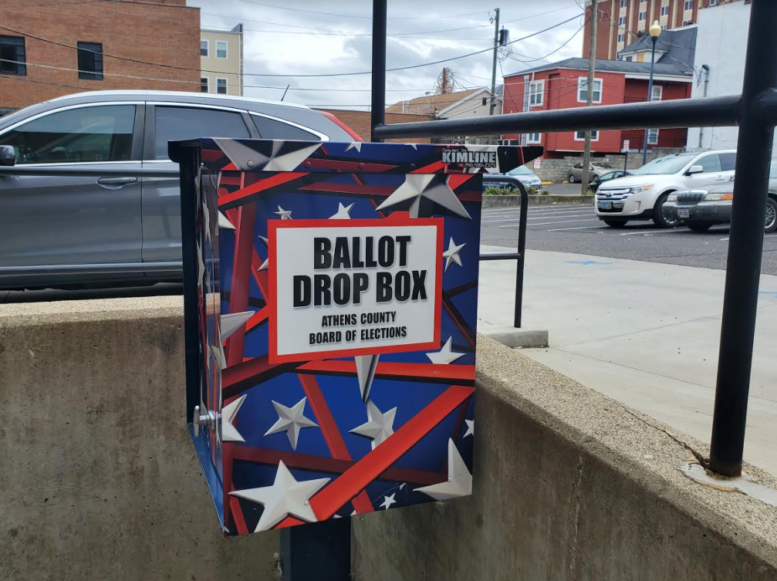

With the directive coming out just a few months before an election, Miller worries many voters won’t know about the changes. She noted their voter education material was already “designed, translated, printed and in the field.” And she contends changes, like drop box signage threatening people with a felony if they deposit any ballot other than their own, are likely to intimidate voters.

“Imagine showing up with your mom’s ballot after the board of elections is closed,” she said. “(You) see this intimidating sign that says you can be charged with a crime or get fined, and then you have to make a decision about whether you rearrange your schedule and come back during office hours.”

For many voters, she argued, making the trip to the county board is a significant undertaking, and requiring some individuals to show up during the hours when the board is open defeats the purpose of a drop box.

The plaintiffs

The latest lawsuit involves two voters and the state democratic party. The party contends it would have to expend additional resources on voter education and turnout because of LaRose’s directive. It argues the requirement will limit access by restricting after-hours drop off and contributing to long lines at county boards of elections, which could deter voters or the people helping to return their ballots.

Another plaintiff, Norman Wernet is planning to return his and his wife’s ballots. After a recent instance of mail theft Wernet wants to use a drop box to ensure their ballots are counted. His wife has early-stage dementia and he’s a senior citizen. “Being forced to park his car, walk up to several blocks, and wait in line to complete an attestation form will be taxing on his time and his health,” the complaint states.

Eric Duffy is blind, and while he has voted in person in the past, he’s had health challenges recently and is planning on voting absentee. Like Wernet, he wants the certainty of the ballot drop box, but the person he trusts to return his ballot “has difficulty walking and standing in line for extended periods of time.” His assistant would have no problem with a drop box but “could not readily return the ballot in person to election officials at the board of elections office.”

The “purpose”

The lawsuit contends LaRose’s directive violates federal law and the state constitution but the most explicit argument deals with state statute.

The section of the Ohio revised code dealing with drop boxes also covers the list of the family members eligible to return a relative’s ballot on their behalf. After listing out 19 different relations, the provision lays out the state’s drop box policy. “Secure receptacles” must be on board of elections property, monitored at all times, and available for drop off 24/7 during the early voting period.

But the complaint zeroed in on a particular phrase in the description — drop boxes are set up “for the purpose of receiving absent voter’s ballots under this section.”

Because the section establishes several explicit provisions, including round the clock availability and the relatives eligible to return ballots, the secretary can’t impose requirements that would curtail voters’ access.

“The Secretary’s issuance of the Directive is thus void,” the complaint contends, “because it violates the Revised Code’s express terms and imposes an extra-legal condition on the return of ballots not imposed by the Ohio General Assembly.”

The Ohio Supreme Court set a timeline Monday for the parties to file briefs. The Secretary’s response is due by noon today, and deadline for the final set of reply briefs is next Monday afternoon.

Also from Ohio Capital Journal:

Communities of color, faith, stand behind Ohio Issue 1 redistricting reform

The heads of prominent civil rights and anti-discrimination groups, along with faith-based groups, have joined a list of supporters of Ohio Issue 1, which would reform the redistricting process by replacing politicians with citizen commissioners.

The Ohio Organizing Collaborative released an open letter signed by more than 60 “Black faith leaders” of churches and religious groups from across the state, saying the leaders felt “compelled to address the urgent and pressing need for citizen-led initiatives to reclaim our democratic processes from the grip of partisan politics.”

“A fair redistricting process will restore our right to representation of Black voices in our state government,” the letter stated.

As leaders of their churches and faith groups, those that signed the letter said they were “called to protect the dignity and autonomy of our congregations,” and for that reason supported changes to the state redistricting process. READ MORE