By JULIE CARLE

BG Independent News

Rick Fruth had been farming his family’s Henry County farm for 20 years when he realized he had to do things differently if he wanted the business to survive his eventual retirement.

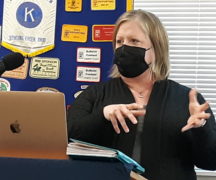

“In the mid to late 1990s, I was farming 1,600 acres, basically as a sole proprietor with some full-time help and my father still working,” Fruth said during Thursday’s Bowling Green Kiwanis Club meeting. “Most people would have said I had a moderately successful operation, but I developed a belief that doing more of what I was doing was not going to get me where I wanted to be.”

The traditional way to grow a family farm operation is to “compete business away from your neighbors to build scale and achieve goals,” he said.

Fruth liked his neighbors, knew they were in similar situations, and didn’t want to grow his farm to their detriment. “From then on, I made it my mission to find a corps of neighbors and develop alliances with them.”

His alliances with the Mark Schwiebert and Rob Rettig family farms started the path to New Vision Farms.

“It really blossomed first with the Schwiebert family,” said Fruth, who had more acres of popcorn contracted than he could grow in one year. He asked about planting and harvesting popcorn on some of Schwiebert’s acreage and in return, Schwiebert could plant and harvest beans for Fruth.

Within four years, the process went from being transactional to full partners. Rettig got on board next. By 2010, the families formed “doing business as” (dba) New Vision Farms operating as a joint business venture, and in 2016, they formally merged the operations.

“We’ve never looked back, and to be perfectly honest, it’s changed my life,” Fruth said, getting a little choked up.

The reasons Rettig got involved were similar to Fruth’s. “Our families grew up a few miles apart and went to the same church. He was a mentor to me,” Rettig said.

He realized they shared the same values and interest in ensuring their farm operations were sustainable.

“We were doing fairly well independently, but I reached a point that I was just tired of keeping all the plates going,” Rettig said. “As a farmer, you’re a marketer, finance person, doing all the elements of management by yourself and trying to make it work and be a father, husband and active in the community at the same time.”

Farmers are known for being jacks of all trade and master of none, he added. “That is not a recipe for excellence.”

The New Vision Farms system allows each owner and staff member in management to specialize. “We have really, highly qualified people in every position,” Rettig said.

For example, because of Fruth’s expertise in finance and accounting, he developed a proprietary accounting system “that is probably the only one like it in the country,” Rettig said.

Mark Hoorman is the company’s agronomy manager in charge of purchasing and planting.

Rettig’s first job with Ag Credit in Bowling Green during the farm crisis of the 1980s significantly influenced his perspective. “We watched a lot of pain, social pain. All this has allowed us to specialize in our management.”

Everybody involved has to be better off or it’s not worth it, he said. That’s the basic principle they have adhered to since the beginning.

Both men agreed that the rewards are more than financial, though financially they are better off than they imagined.

“It’s been personally rewarding watching the development of people and watching the families become blessed because of it,” Rettig said.

Each farm involved in the operation still exists as a landowner, but it becomes a landlord to New Vision Farms, Fruth explained. To date, the company works with more than 60 landowners, on a proprietary rental system.

According to the New Vision website, proprietary flexible rent agreements are “designed to cultivate long-term, mutually beneficial relationships.” With a focus on engaging with additional landowners, the website states, “Our goal is to improve your farm using sustainable farming practices. No matter the amount of land you own, we have the equipment, experience and esteem for you – the landowner – to exceed your expectations.”

New Vision Farms has implemented an innovative benefit for the landlords called “risk pools” that allows them to be a part of a pool of up to about 4,000 acres.

For those who buy into the risk pools, “instead of getting 50 percent of their 100 acres, they get 50 percent of 4,000 acres,” Rettig said, spreading the landowner’s risk across 4,000 acres.

“They don’t care if their field is planted first or last, but they do care if their property gets a hailstorm. With risk pools, they are getting a percentage of everyone else’s,” he said. “They will care that we are farming 4,000 acres that makes everyone the most money.”

It’s a system where everyone has skin in the game. Everyone shares the risks and the rewards.

Even the vendors and customers appreciate the business.

New Vision’s impact on the popcorn industry is the best example, Fruth said. They grow approximately 2% of the nation’s popcorn and sell worldwide.

“As New Vision Farms, we found we had more influence,” Fruth said. “If the West Coast needs more popcorn, we have those relationships to help. The scales are more than we thought they were.”

New Vision Farms gets thumbs up from academics

“Academics think this is a perfect model” for agricultural sustainability, Fruth said. “However, in general, most people don’t farm to be in business to share with others. They would rather be independent to go faster and be in control,” Fruth said.

“We are not transactional people, but relational,” Rettig said. “You know you’ll go faster by yourself, but you’ll get a lot farther with others.”

It’s that independent streak of farmers and farm life that makes the New Vision Farms model unlikely to catch on, he said.

Another significant stumbling block for other farmers interested in the concept is the importance of shared values and trust, Fruth said.

“You have to get over the mentality of yours and mine. It’s ours,” Rettig said. “We realize how special this is, that we share the same values and can trust each other to work things out.”

The concept is not as popular or doable as one would think.

“We’ve presented at conferences and often have people come up to us crying because they can’t find others interested in the model who they can trust or have the same principles,” he said. “It’s kind of sad because it could really help a lot of families.”

Instead, nearly 80 percent of family farms go out of business when the father or grandfather retire.

“There are a lot of ex-farmers,” he said. “But we are a family of family farms. This is a way to have success and continuity.”