By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Viewers are greeted to “Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992” by a video of Jessye Norman singing Purcell’s “Dido’s Lament.” The mournful aria about being laid to rest in the earth is laid out in its full, glorious length before the six cast members romp onto the stage to a hip hop beat that morphs into “Surfin’ USA.”

The Black Swamp Players production directed and designed by D. A.-R. Forbes-Erickson, seems calculated to keep the viewer off balance – all the better to immerse them into the chaos that follows.

“Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992” reports on the civil unrest that followed the not guilty verdicts in the trial of four Los Angeles police officers in the beating of Rodney King, the year before. The production is on stage at the Players’ home theater at 115 E. Oak St. in Bowling Green, Wednesday through Saturday (May 25-28) at 8 p.m.

The play by Anna Deavere Smith is a pioneering work of documentary theater. She used verbatim interviews to create the script, writing while the riot was still in the headlines. The heat of the riots and related incidents burns through. She doesn’t stint on complexity or controversy.

As envisioned by Forbes-Erickson, the cast of eight takes on a host of real life characters without concern seemingly for ethnicity nor gender, forcing us to see the humanity behind race, gender, age, social class. (The play was originally done by the playwright as a one-woman show.) Appearing in the show in multiple roles are: Steve Bishop, Isabel Contreras, Heath Diehl, Pella Felten, Monica Hiris, Ebere Okoro, Leah Truman, and Deb Weiser.

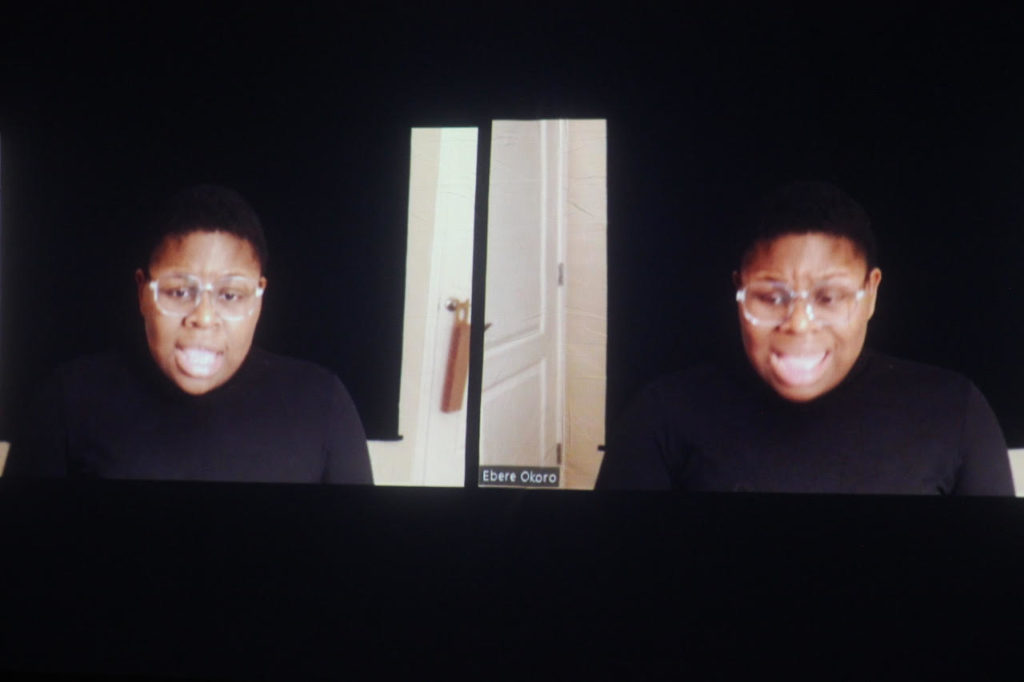

Photos of the actual witnesses are projected while an actor voices their lines. The power of those gazes staring out from the screen sometimes subsumes the powerful work of the actors. The words become associated with the person on the screen as much as with those on stage. And yet having the community actors bringing these lines to life helps to inject these stories into our lives.

The racial tension at the heart of the riots was multi-dimensional, not just Black and White. Tension existed between Korean shopkeepers and their Black customers. This exploded two weeks after King’s beating when a shopkeeper shot and killed a Black teenager he suspected of stealing orange juice. The shopkeeper was successfully defended by a Black lawyer, for which the lawyer was condemned.

We don’t hear from Rodney King, but from his aunt (Contreras).

We see the riots from all sides. Radical Paul Parker (Felten) celebrates the uprising as a victory; Elaine Brown, a former president of the Black Panthers (Truman), dismisses the riot as quixotic. Ask Saddam Hussein about the armed might of America, she suggests. The play is bookended by testimony from two jurors. A juror in the criminal case (Felten) decries the revelation of their names and addresses in the press. But he is most disturbed when he receives mailing from the KKK inviting him to join. At the end we meet Maria (Hiris) a juror in the federal civil rights trial that followed the criminal trial. The police officers were held culpable in that trial. She speaks of the tensions in the jury room that echoed the tensions out on the street. But once those apprehensions and that distrust were broken through, the jury quickly came to a verdict.

In a cubist touch, Bishop reads the lines Reginald Denny, the truck driver pulled from his truck and beaten, before being rescued from the scene by several Black Good Samaritans. Afterward he was only interested in promoting peace. Bishop also voices the words of a White man enraged by Denny’s beating who a dissects a video of the scene as well as the words of a Black witness unsympathetic to Denny’s plight.

The raw street language is contrasted with the erudition of Cornell West (Bishop) who observes that Black Americans live perpetually in the Saturday between Good Friday and Easter. They revel in the “purple” of neither the deep mourning of Good Friday nor the celebration of the Resurrection. That’s celebrated, he tells us, in the art of John Coltrane and Toni Morrison.

Jessye Norman (Weiser) addresses the importance of song in helping her people live through oppression, and says maybe if she were starting to sing now, what would come out would be a roar.

We don’t hear from the four police officers accused of the beating, but from a police sergeant (Diehl) who opines that the beating of King was meant as a message to the city’s political leaders about what comes from their banning the use of choke holds.

And we hear from the police commissioner (Truman) who goes to talk with gang members at the urging of U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters (Felten in a later scene) and is accused by police of talking with the enemy.

We hear from a clerk (Okoro) in on two screens, talking over herself, the confusion of words and emotions.

All this creates a kaleidoscopic tsunami that crashes over the audience. Though the play and the events that inspired it are now three decades in the past, it opens two years to the day that George Floyd died at the hands of police, a sad reminder that the issues “Twilight” addresses are still with us and still waiting to be solved.