By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

The Pulitzer citation honoring West Virginia reporter Eric Eyre for investigative journalism notes his “courageous reporting.”

In a virtual question and answer this week, Eyre would have none of that.

The courageous ones are the addicts who enroll in a treatment program “and stick with it.”

“It’s really hard,” Eyre said. It can take three to five years.

And there are people such as Debbie Preece, whose brother died of an overdose, and has now made it her life’s work battling those behind the opioid addiction crisis. She trails drug distribution trucks over the winding roads of West Virginia.

When she started working with Eyre on the investigation into opioid crisis, she was afraid she’d be run out of town. It also meant dredging up her own drug-related legal problems from two decades before.

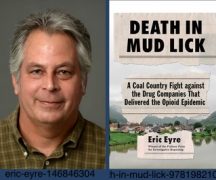

The session, hosted by Gathering Volumes book store and the Archbold Community Library, was held on the same day that the paperback edition of Eyre’s book “Death in Mud Lick: A Coal Country Fight Against the Drug Companies That Delivered the Opioid Epidemic” was released.

Speaking remotely from West Virginia, Eyre answered a set of questions posed by pharmacy students from Ohio Northern University.

The coronavirus pandemic has “exacerbated” the opioid crisis, Eyre said. While places such as Cabell County in West Virginia had made strides, the number of overdose deaths has now increased again.

And the opioid epidemic which had been largely a rural crisis, has now reached into cities. Washington D.C., he noted, experienced a 64-percent increase in overdose deaths. That would have been unheard of 15 years ago when the problems of opioid addiction took root in rural America.

Eyre explained places like West Virginia were primed for the influx of opioids.

The populations, often living in poverty, already suffered from chronic health conditions. Often they labor in jobs “that are literally back breaking work.”

The typical path to addiction, he explained, may start with a back injury in a coal mine. The worker then goes to a legitimate doctor who prescribed opioids for the pain. By the time the patient had recovered and was no longer in pain, they are hooked on opioids. To feed their addiction, the patient would enter into “the Wild West” of pain treatment clinics, which hand out prescriptions for pills freely.

Those prescriptions were then brought to pharmacies that had no scruples about handing out the pills. It didn’t matter if the person was from a distant state or had been in the week before or if the doctor who wrote the script had lost his license to practice. Sav-Rite in Kermit, population 382, had a line of customers outside every day. Customers would have pill parties next to the building. The business brought in so much money, Eyre said, that they couldn’t shut the cash drawers. Even when the shop’s prolific sales of opioids were brought to the attention of distributors such as McKesson, nothing was done.

Eyre’s reporting eventually resulted in charges being filed, though the pandemic has delayed the trial.

Eyre moved to West Virginia 22 years ago after completing graduate school. He expected to stay for two years. He took a job at the Charleston Gazette-Mail, and became a state house reporter. He got involved in looking at the opioid crisis while reporting on a charge of conflict of interest by the state attorney general. The attorney general’s wife lobbied for Cardinal Health, and the company had made a generous donation to his inauguration party.

Eyre said that there’s “a real sea change in how we get information.” Instead of submitting themselves to interviews, politicians ask for questions in writing. Instead of answering the questions directly they may hold a press conference, or issue a statement which doesn’t answer the questions, or merely post a tweet. Reporters then have to file public records requests for information that should be readily available.

Eyre now works with the Mountain State Spotlight a non-profit news outlet that employs young reporters through the Report for America project. He said he enjoys working with young journalists interested in pursuing in-depth reporting on issues such as poverty and the opioid epidemic.

Asked what can be done about the opioid crisis, Eyre spoke in favor of providing clean needles to addicts. This is “a political football,” he said. When West Virginia outlawed those programs, the rate of HIV went up.

He does not believe legalizing marijuana will have any effect on the number of people getting addicted to opioids. An early study indicating fewer deaths in states with legalized marijuana has been contradicted by another study. And he strongly opposes legalizing heroin and fentanyl.

“If you know someone in recovery,” Eyre added, “talk to them and give them a hug.”