FILM REVIEW By CARROLL McCUNE

In 1872, when the Osage Nation was forced to sell their fertile land in what is now Kansas and purchase the worst land possible in northcentral Oklahoma, they never could have imagined that this move would precipitate a Reign of Terror and make them the richest people per capital in the country.

The Oklahoma Historical Society, states that the new reservation’s oil resource-rich lands generated more wealth than all of the American gold rushes combined in just two decades. Meg Standing Bear Jennings, sister of the current Osage chief, speaking in David Bishop’s Smithsonian documentary America’s Hidden Stories: The Osage Murders said:

“White prospectors leased oil fields from the tribe, making the Osage so rich that one California newspaper deemed them the “most to-be-envied” people in the country. A 1920 analysis estimated that each Osage received around $10,000—roughly $153,000 today—annually. [Osages] traveled in Cadillacs and Lincolns, and they had flamingos and peacocks.”

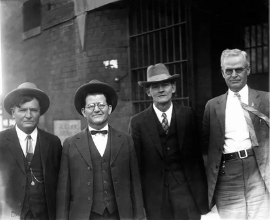

1926 Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Terry P. Wilson, writing in The Osage (Indians of North America), said that each of the tribe’s 2,229 members in 1907 received a headright, or share in oil money that could be inherited but not sold. Non-native people were eligible to inherit headrights, so fortune-seeking white settlers could obtain shares in the tribe’s oil rights by marrying into an Osage family, maneuvering their way onto an Osage’s list of heirs, or deceitfully obtaining guardianship control of an individual’s assets.

A sinister conspiracy developed involving criminals, ordinary people, and the prominent citizens of Gray Horse, Oklahoma, in order to swindle allotted members of the tribe out of their oil money. It led to the known murders of twenty-four tribal members, two investigators, and between the years 1907-1931, possibly as many as 400 suspicious deaths. This shameful episode has been lost to American history—that is, until now.

David Bishop, a descendant of one of the murder victims, claimed that the historical memory of the murders was deliberately suppressed by tribal members themselves out of paranoia, a need for catharsis, and embarrassment. The Osage do not like to see themselves as victims.

Commenting on his book Killers of the Flower Moon: the Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI, author David Grann thinks that the conspiracy against the Osages was lost to history because of collective white guilt. He said:

“You have morticians covering bullet wounds, doctors who were administering poison, businessmen and lawmen who were on the take, and many others who remained complicit in their silence…But there were so many people, including myself, who had never been taught this [history]. We had never learned it. We had effectively excised it from our conscience.”

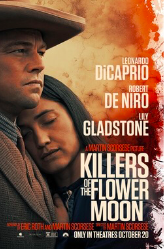

When New Yorker journalist David Grann published his book in 2017, the iconic filmmaker Martin Scorsese knew he wanted to produce a film based on the #1 New York Times best seller. This true story epitomized Scorsese’s dominant themes of social pathology and the banality of evil.

Because a film can never encompass the scope of a literary work, the director focused only on the serial killings; disregarding the last half of Grann’s book that tells how J. Edgar Hoover, founder of the FBI, usurped all the credit for agent Tom White’s courageous work solving the Osage murders. He also subordinated the Osage point-of-view to a plot of his own making about love and betrayal. The film, however, does portray the stultifying impact of the Reign of Terror on Osage culture and successive generations. Actor Lily Gladstone, a Blackfoot /Nimiipuu native commented:

“Never forget this story is recent history with a lasting impact on breathing, feeling people today. It belongs to them, and we all have so much to learn from it…And this story is a lot to take in. Be kind, and please be gentle with each other. There is much to process, and much to heal.”

The movie’s story line centers on the relationship between the duplicitous rancher/deputy sheriff William Hale (Robert De Niro), and his dull, morally conflicted nephew Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio). It dramatizes a presumed love affair between Ernest and his Osage wife Mollie (Lily Gladstone)—a romance never articulated in Grann’s book. Jesse Plemons appears as Tom White, a quintessential federal agent sent to crack the case of the Osage Reign of Terror after local investigators failed or turned up dead.

Earnest Burkhart subsequently became the film’s protagonist rather than the federal agent Tom White, the hero of Grann’s book. Interestingly, DiCaprio had been slated to play the calm, dignified lawman Tom White, but he convinced Scorsese to let him tackle the manic character of Ernest Burkhart, which was a good decision. DiCaprio transformed himself into the essence of a tormented soul wrestling with his conscience and emotions. Rolling Stone critic David Fear aptly described the actor’s challenging role as “a murderer under the sway of a Svengali and in love with his victim.”

The three-and-a-half-hour extravaganza has been classified variously as a western crime thriller, love story, historical epic, docudrama, and book adaptation. Described as an indictment of America’s treatment of natives, a reckoning with the past, and an orgy of myths of the entertainment industry, Scorsese’s script has also been critiqued for its insufficient emphasis on the Osage perspective.

But issues of ethnic representation do not lessen appreciation for this work of filmic art produced primarily for the edification of a non-Native audience. Ultimately, only the Osage can define themselves and determine their true place in the history of peoples who have walked the earth. Filmmakers are accountable only to the requirements of their art—to film’s form rather than to film’s function as cultural propaganda.

Although when Scorsese told the current Osage chief Standing Bear that he intended to tell the story through the eyes of Ernest (a white man) and Mollie, Standing Bear urged him not to “lose the voices of the Osage.” In the end, this movie is not about the Osage, but about what was done to them through the conniving greed and callous indifference of conscienceless men.

Scorsese and co-script writer Eric Roth expressed an overriding desire, however, for authenticity in making Killers of the Flower Moon, if not fidelity to Grann’s narrative. To the filmmakers, authenticity apparently means accurate depiction of costume, settings, language, and period. They consulted with Osage tribal members and recruited them as actors, language tutors, and culture advisors.

The filmmakers were also concerned with cinematic authenticity. Mexican cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto created a 1920’s-period looking movie by shooting on film and with coated lenses; it made the imagery softer with more distortion around the edges. To enhance the impression of historical authenticity, the director inserted archive newsreel footage of the serial murders and hunt for the killers. The late Robbie Robertson incorporated into his original soundtrack authentic native ceremonial songs, drums, and flutes together with early blues and slide-guitar.

Scorsese devised a surprise ending by stepping into the picture himself as a 1920’s radio personality in a program called The Lucky Strike Hour during which the radio cast reported in vaudevillian style the denouement of the Osage Reign of Terror. It was an abrupt, baffling shift in tone from the somber mood of the rest of the movie. Also, a viewer needed to have read Grann’s book in order to get the connection between the Osage murders and The Lucky Strike Hour, which was a satire on Hoover’s FBI.

Perhaps this satirical concluding sequence was an attempt to deal with the latter part of Grann’s book in just a few minutes. This was unfortunate because the latter part of the book reveals the whole truth about the Osage murders, Tom White’s ironic life and, according to Grann, White’s frustrated efforts to publicize “the more terrifying conspiracy that the bureau never exposed.”

A Paramount Production, Killers of the Flower Moon includes Native American actors Tantoo Cardinal, Cara Jade Myers, JaNae Collins, Jillian Dion, Tantaka Means and many others. It is playing now in theaters and will be available streaming on Apple TV+ soon.

MSNBC Joe Scarborough’s interview with Martin Scorsese

Festival de Cannes: Director and Cast Press Conference

America’s Hidden Stories: The Osage Murders documentary by David Bishop