By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Like his father, Quinn Pemberton was a kid who loved reading.

Writer, corporate executive, and activist Steve Pemberton recalled reading “The Lion and the Mouse” to 6-year-old Quinn. It was the youngster’s favorite book and no matter how often he heard it, he had questions.

One day he looked up at his father in a way that let Steve Pemberton know his son had something else on his mind.

“He asks me if when I was a little boy did I have a daddy?”

Pemberton knew this question was arise someday, but not this soon. Quinn is the oldest of his three children.

No, Pemberton responded.

Did he have mother?

Again, no.

He could see Quinn was confused. What kind of world was this without a mother or father?

Pemberton knew then that he had to write his story out. The result was ”Chance in the World,” which was published in 2014 and turned into a movie in 2018.

Pemberton was the guest speaker last week at Bowling Green State University’s online celebration of its first generation students, and the TRIO program that provides them the assistance they need.

The title of his book comes from a note left by a babysitter who wrote of Pemberton as a toddler: “This little boy doesn’t have a chance in the world.”

Soon after, at age 3, Pemberton was taken away from his mother, who was an alcoholic, and placed with foster parents, who abused him for the next 13 years.

Pemberton defied that early prediction. The native of New Bedford, Massachusetts went on to graduate from college, showed corporations how to diversify their work forces, and eventually authored that book.

In the end of his presentation, he proudly displayed a photo of his family, with his wife, Tonya, and three children with Quinn now, like his father, attending Boston College.

He achieved all this through the guidance of “lighthouses,” those people who stepped up and helped him despite what seemed as his poor prospects.

That family trauma went back three generations. His mother was raised by an alcoholic father. His paternal grandmother died at 40 leaving 13 children orphans. No one knew what to do with Pemberton’s father so he was placed in a juvenile detention center. The heartbreak and anger he endured stayed with him his entire life.

He was the third generation to be orphaned, Pemberton said.

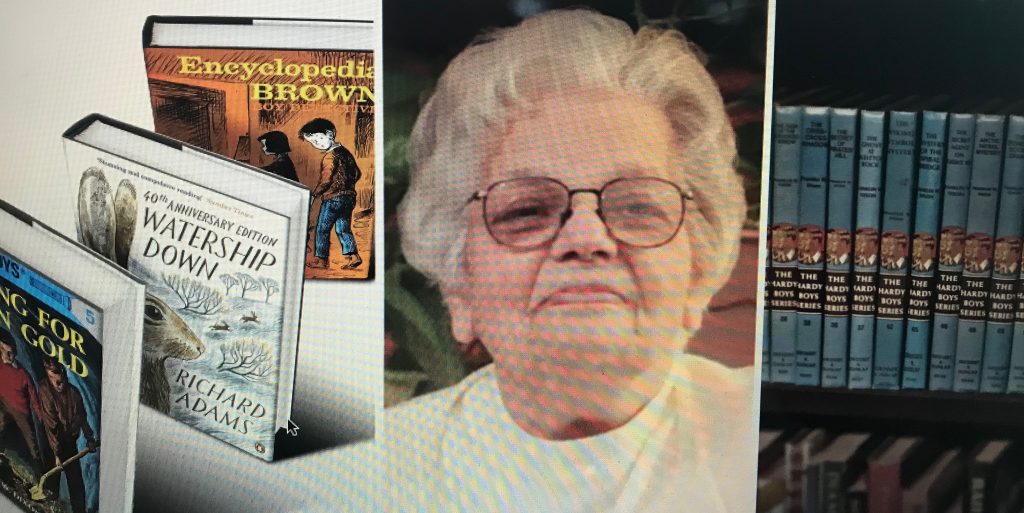

His one solace was reading. He especially liked mysteries. He was a mystery to people – dark complexed with blue eyes and a Slavic last name. “Pemberton” is his father’s surname, which Steve took later in life. No one knew what to make of him.

His foster family forbade him to read in their presence. “Reading books was fairly dangerous for me,” he said. So, he did it secretly.

One day reading in a park, a woman approached him and asked what he was reading. He showed her the book.

That’s what you were reading last week, she commented. He told her when he finished a book, he just went back and read it again.

About a week later, the woman showed up at his foster family’s home and dropped off a stack of books for him.

As an adult he met the woman, Claire Levin. Asked why she did this, she responded, that she it was nothing extraordinary. “I did what her mother had always told me to do. Whenever you can, give from wherever you are whatever you can.”

She didn’t have much, so she just passed on the books her three sons were finished reading.

Being an avid reader meant Pemberton became an accomplished speller. Though otherwise shy, when it came to the spelling bee, he stood out. Yet when he progressed from the classroom bee to the stage for the school-wide bee he was uncertain what to do. He looked over at the judges, and one of them caught his eye, gave him a smile, and gestured with her eyes toward the microphone. She did that every time it was his turn.

In high school, he learned about the Upward Bound program from a friend. This promised to be a path toward college. Pemberton peppered the friend with questions. Go to the Upward Bound office, he was told.

So, he did. He met the director. She was a familiar face – she was judge from the spelling bee.

Ruby Dottin was an activist and a force to be reckoned with in New Bedford.

When Pemberton’s foster family refused to consider sending him to college, she made sure they were overruled.

Pemberton’s situation finally became intolerable to him, and at 16, the week between Christmas and New Year, he left the foster home.

His social worker struggled to find a family to take him in. It was a hard sell. He was 16 and “I had this enormous case file following me around that said I didn’t have a chance in the world.” After calling people long into the night, she asked him if he happened to know anyone.

He remembered overhearing the assistant director of the Upward Bound program telling another teacher that he didn’t have children but if he did he’d want them to be “just like Steve.”

They called John Sykes, a bachelor, he agreed to take Pemberton in until other arrangements could be made.

That stretched into a year and a half when Pemberton enrolled in Boston College.

Sykes pushed him to succeed. When Pemberton questioned whether he belonged in Advanced Placement English, Sykes told him to check the reading list. Pemberton had already read most of the books on it.

On college graduation day he was alone – Sykes had a conflict and could not attend. Seeing other students with their families, Pemberton decided he needed to seek out his biological family laying the groundwork for his book.

But, he said, “there was no bigger family for me than Upward Bound.”

Speaking virtually to students, he urged them to be lighthouses.

These people are “seemingly ordinary.” They aren’t on the nightly news nor do they have large social media followings. “They are fairly humble people,” he said. “All of us have had lighthouses. “

It was clear to him that he had to be there to help others.

“Let your life be a lighthouse,” Pemberton said. “There are so many lives out there that need the power, the gift of your example.”