By JULIE CARLE

BG Independent News

From the time the moon first touches the disk of the sun until it completes its path during the April 8 eclipse, Bowling Green area residents and visitors will experience a rare opportunity.

The eclipse’s two-and-a-half hours from start to finish – from 1:56 p.m. to 4:26 p.m. – will be a show, but the showstopper will be in the nearly three minutes of totality that reaches maximum “oohs and ahhs” at about 3:12 p.m.

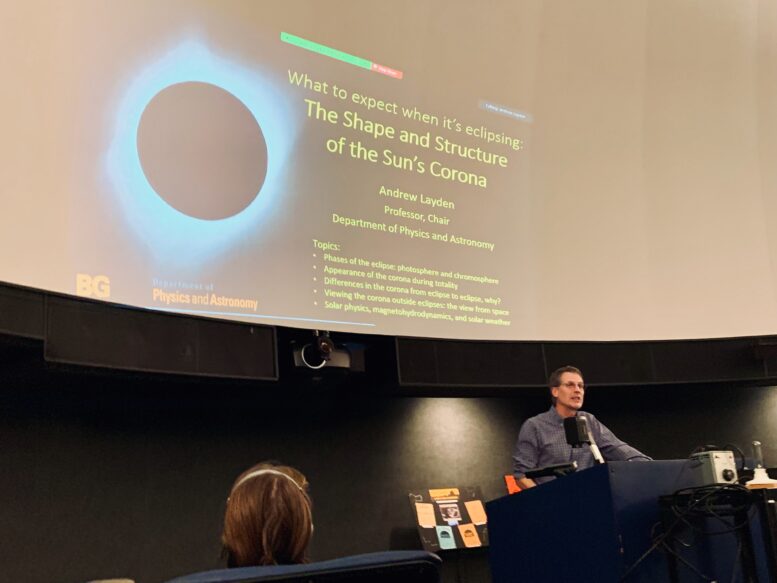

“Within those precious few minutes, when the moon completely covers the bright surface of the sun, the corona shines out,” said Dr. Andrew Layden, chair and professor of Bowling Green State University’s Department of Physics and Astronomy.

During the second of BGSU’s Total Eclipse Speaker Series, Layden explained some of the important terminology and described some phenomena that spectators might expect from the solar event.

The corona is the pearlescent outer atmosphere of the sun that is usually too dim to observe directly. However, the corona becomes visible when the moon completely covers the sun during an eclipse. Only during totality is it okay to view the corona without eclipse glasses, he said.

“As soon as the moon moves out of the way and the photosphere (another outer layer of the sun) shines through, you need to get the eclipse glasses back on to continue to watch,” he said. “We are working hard to be consistently informing people about safe solar viewing.”

With each solar eclipse, the appearance of the corona can vary. In some years, the corona may look like the petals of a sunflower. In other years, the corona may look like iron filings in a bar magnet field, Layden explained.

Scientists believe there is a correlation between the number of sunspots on the sun and the appearance of the corona. Sunspots—where the magnetic fields are found—are present on the surface and appear as a dark central spot surrounded by a lesser dark region.

“The sunspots are the first indication that there are magnetic fields in play on the surface of the sun,” he said. “If we average sunspot counts over a month, it’s a pretty good indicator of solar activity and magnetic activity on the sun.”

Despite the complexity of the sun’s magnetic fields, there is a pattern that shows up and repeats, with the time between the two peaks typically about 11 years, give or take a few years. In the years when the sunspot numbers have been above 200, the corona usually takes a radial shape, like the sunflower. In the years when the sunspot numbers were low, the corona appears to be more dipolar, like the bar magnet, Layden said.

With sunspot numbers appearing to be increasing, he predicts this year’s eclipse is likely to boast the sunflower corona.

The magnetic fields on the sun’s surface loop out and then back into the sun, Layden explained. “In the places where those magnetic fields cross the photosphere, they trap the gas that can’t move away or escape. The sun still shines but the magnetic fields get rid of the energy and cool off.” The spots look black but the gas is still very hot.

Two other layers of the sun’s atmosphere are also significant, he said. They include the photosphere, the most familiar, visible surface of the sun, and the chromosphere, the colorful layer between the photosphere and the corona that is comprised primarily of hydrogen and helium gases that may produce pinkish or red bursts of light.

Two special effects are possible during the eclipse as the last sliver of the photosphere is being eclipsed by the moon’s dark shadow,” Layden said.

“We get a couple of particularly exciting treats that I want you to expect and look for”—the Diamond Ring Effect and Bailey’s Beads, he said.

The Diamond Ring Effect is a little sliver of light that shines brightly like a diamond as the corona starts to be visible around the darkness of the moon. The effect usually happens during about the final 10 seconds before or after the moon completely covers the photosphere.

“I can’t tell you how profoundly deep and dark the unlit side of the moon is. It’s just stunning and beautiful,” he said, suggesting viewers watch carefully because it only lasts for a few seconds.

Bailey’s Beads “are even more fleeting,” and are created when the photosphere shines brightly due to some of the uneven topography of the moon. Mountains and valleys on the moon interrupt the photosphere’s light, but the beads are difficult to predict and if visible, last only for a brief moment, he said.

During BGSU’s April 8 eclipse event at the football stadium, there will be telescopes set up and properly equipped with their own version of eclipse glasses. Spectators will be able to see details such as the sunspots during the eclipse. They also are working to use the telescopes at the planetarium’s observatory to stream live video to the jumbotron at the stadium, and possibly to WBGU-TV and other regional and national television affiliates.

The highlights from the colorful layer of the chromosphere during the eclipse include the possibility of seeing prominences – the light glowing from the hydrogen gas as loops and sprouts through the sun’s surface.

The schedule for the remaining Total Eclipse Series talks at 7:30 p.m. in the planetarium following a planetarium show (except where noted) follows:

- Tonight (Feb. 8): “A Dragon is Eating the Sun But we Knew That Would Happen… or Not” by Allen Rogel, teaching professor of physics and astronomy.

- Feb. 15: “Nature in Music: The Weird and Wonderful” by Emily Freeman Brown, professor, College of Musical Arts.

- Feb. 22: At 6 p.m. at the Wood County District Public Library, The Reddin Symposium in Canadian Studies presents “The Sky Has No Borders: Perspectives on Astronomical Knowledge from Canada, Mexico and the United States.”

- Feb. 29: At 5:30 p.m., “WBGU Eclipse Activities For Kids” by Kelly Pheneger, director of education and outreach at WBGU, and Laural Kirchner, coordinator of education and outreach at WBGU. “It’s About Time” planetarium show explaining the Feb. 29 Leap Day will be shown at 6:30 p.m.

- March 7: “Sounds of the Solar Eclipse, Exploring the Music of Solar Eclipse Demonstrations in Planetariums” by Colin Hochstetler, music researcher, Polka preservation assistant, BGSU Music Library and Bill Schurk Sound Archives.

- March 14: “Eclipses and Astronomical Phenomena in Art History” by Andrew Hershberger, professor, BGSU School of Art.

- March 21: “Eclipses in Mexican History” by Amilcar E. Challú, chair and associate professor, Department of History.

- March 28: “Astrophotography for Amateurs” by Christopher Dietz, associate professor, College of Musical Arts.

- April 4: “’These Late Eclipses’: Shakespeare and the Early Modern Sky” by Stephannie Gearhart, chair and professor, English.

The weekly events are free and open to the public. The speaker series talks are also available as a live-stream event; the links are included on the event page.