By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Reporter Wil Haygood had to watch two episodes of “The Price Is Right” before he could start interviewing Eugene Allen and his wife, Helene.

Haygood had come to the Allen home because he was interested in hearing about Allen’s experience as an African-American butler in the White House. In the living room there was little sign of his former employment. A single photo with Nancy Reagan. Only after two hours of talking did Helene Allen turn to her husband and say. “You can take him down now.”

That’s when Haygood went down with Allen into the basement. Walking gingerly in the dark, Allen clung to the reporter’s arm, until they found the light switch.

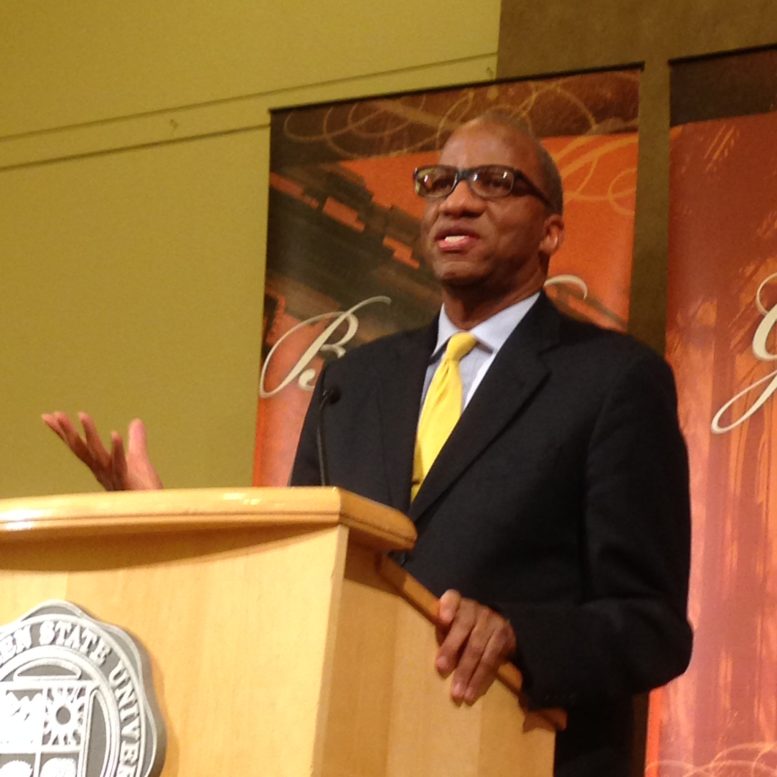

When the light went on, Haygood saw what looked “like the most gorgeous room in the Smithsonian Museum.” The writer related all this to an audience last week at Bowling Green State University’s commemoration of Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Allen’s basement walls were lined with photos and memorabilia from decades of service in the White House. There were presidents and royalty – Duke Ellington for one. There were gifts, including a Stetson hat given to him by Lyndon Johnson, given to Allen by the presidents he had served. Among the items were 20 photo albums.

Here was history in all its glory, in the basement of a modest Washington house.

Haygood asked Allen if anyone ever written about him.

“If you think I’m worthy you would be the first,” Allen replied.

“That hurt to hear that,” Haygood said.

Here was someone who had served his country faithfully. Here was someone who loved his country, but because of the color of his skin that love was seldom reciprocated.

Only later did Haygood learn that Helene Allen had long been trying to interest someone in telling her husband’s story. Now that dream would come true, but too late for her. On Sunday, feeling tired after spending time with her family she retired early to bed. The next morning, a day before the election that would put the first African-American in the White House, her husband woke to find she had died in bed next to him.

She didn’t live to see that story Haygood wrote on the front page of the Washington Post — a story that publications around the world published. She didn’t live to read the book that grew from that article, and she didn’t see the movie it inspired “The Butler,” starring Forest Whitaker as a character modeled on Eugene Allen.

Haygood said that the inspiration for the news story came to him earlier while traveling with Obama on the campaign trail. In Raleigh, North Carolina, he met three young white girls waiting to see the candidate. They were crying. Their fathers had kicked them out of their homes because they intended to vote for a black candidate. That cemented for Haygood the notion that Obama, still an underdog at that point, would win.

Coming off the trail he pitched a story to his editor at the Washington Post: Find a black service worker who’d been employed in the White House during the days of segregation. The editor gave him a few days to find his subject, and if he didn’t he’d have to return to the campaign trail.

Haygood called around. The White House staff was no help. Then a call came about a Eugene Allen who had served two presidents. The caller said she saw this man get into a taxi at the White House. She had a name that was all. Haygood’s writer’s instincts took over. If Allen took a local taxi he must live in the metro area. Haygood went to the Post’s library and returned with telephone directories. He started to call – one, two, 10, 20, up to 50 calls. “Eugene Allen” is not an unusual name. Then on call 57 he reached the man who for him was the Eugene Allen. Yes, the man who answered the telephone said. I worked at the White House but not for two presidents, for eight presidents.

That’s how Haygood ended up at the house, watching “The Price Is Right.” That’s how he came to be ushered into the basement sanctuary.

That’s how he learned the story of this man who was at the center of political power as history unfolded. He was there when Emmett Till was murdered, sparking a national outcry against lynching; when Eisenhower sent federal troops to enforce the integration of Little Rock schools; when Johnson signed the Civil Rights Bill, and later the Voting Rights Act.

And Allen was there when Martin Luther King Jr. visited then Vice President Nixon. Leaving the meeting King said to Allen: “Hey brother, I like the cut of your suit.”

Then King asked him to “take me to my people,” meaning those who worked in the basement of the White House.

Allen was also working in the White House the day King was assassinated. Washington D.C., like so many cities, erupted as the frustrations of African-Americans boiled over. As his city burned, Haygood said, “Allen walked to work. He told himself that the first family needed him.”

When the first black president was sworn in, a frail Allen accompanied by his son, Charles, and Haygood made his way to the ceremonies. The first inauguration he’d been invited to. He had on a new coat, and wore a gold tie clip he’d been given by John F. Kennedy. Haygood has that tie clip now and wore to speak. As Barack Obama was inaugurated, Allen whispered to Haygood: “When I was in the White House you couldn’t even dream that you could dream of a moment like this.”

How far the country still has to go, though, was evident when the film rights to Haygood’s book “The Butler” were purchased.

“Hollywood didn’t want to make this film,” Haygood said.

Studios were unwilling to finance the film, so the producers had to turn to private investors such as Sheila Johnson, co-founder of BET. The movie had 41 producers, according to the Hollywood Reporter.

The actors, including Oprah Winfrey and seven Oscar winners, all took a cut in pay to participate.

“Lee Daniels’ The Butler” opened at number one at the box office and stayed on top for weeks. That meant, Haygood said, that whites and blacks, as well as Asians and Hispanics, all liked the movie. People want good cinema, he said.

“The people who run Hollywood are so backwards they didn’t want to make it.”

The film has now been shown in 77 countries, Haygood said. In China it is taught in schools.

But Hollywood still doesn’t get it. Winfrey was nominated for her acting in the British Academy of Film and Television Arts awards, but not for an Oscar in her native land. The all-white slates of Oscar nominees this year, only shows how little has changed, Haygood said.

Cable is much better, he said, presenting a stories about blacks, transgender people. “Cable is in the real world; Hollywood is not,” he said. “If it doesn’t get on board it will vanish and it will be their own fault.”

“The Butler” Author Serves Up History From the Basement