By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Lanisa Kitchiner has spent a lot of time traveling with her son to chess tournaments across the country with her son Levi Valentine. That means she sits outside closed rooms while her son plays, waiting to find out the outcome. This leaves her plenty of time to think about her passion for African art, and chess, and how they intersect.

The waiting led to a professional gambit “Strategic Interplay: African Art and Imagery in Black and White,” now on view the Toledo Museum of Art. The free exhibit is in the Canaday Gallery through Feb. 23.

Kitchiner, the museum’s senior manager of interpretation and African Art curator, has drawn on loans from prestigious collections and the TMA’s own holdings including recent acquisitions, to stage a striking — and despite the subtitle — kaleidoscopic exploration of chess and African art.

Chess, Kitchiner explained, first made its appearance in Subsaharan African in the seventh century with the spread of Islam. Similar strategic games were in play. While these roots are touched on, including a gaming piece from 1300s BCE, which is the oldest piece in the show by millennia, the focus of “Strategic Interplay” is how the game is depicted in art. The interplay is between the aesthetic of African artists from the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries and the art of Europeans from the same period.

The museum has recently acquired a Baga Nimba Shoulder Mask, made in the 20th century for traditional ceremonies. This was the piece that inspired Picasso’s vision of the “ideal woman,” the curator said.

Other images use the chess board to study social hierarchy and royalty.

Togo artist Modupeola Fadugba explores the relationships within a polygamist marriage in the triptych “Take Back Your Pearls.” The king looks out pensively beyond the viewer, maybe to the future. His first wife in the frame with him and to his left the second wife stare into the viewers’ eyes while the third wife glares directly at the king.

Kitchiner said she thinks they’re all giving him the side eye. This drama plays out on a chess board.

Chess is used as well to depict the conflict between European colonizers and indigenous Africans. That’s evident in two sets created by French artists. Another nearby set was made by a Tanzanian artist to tap into European demand for African art.

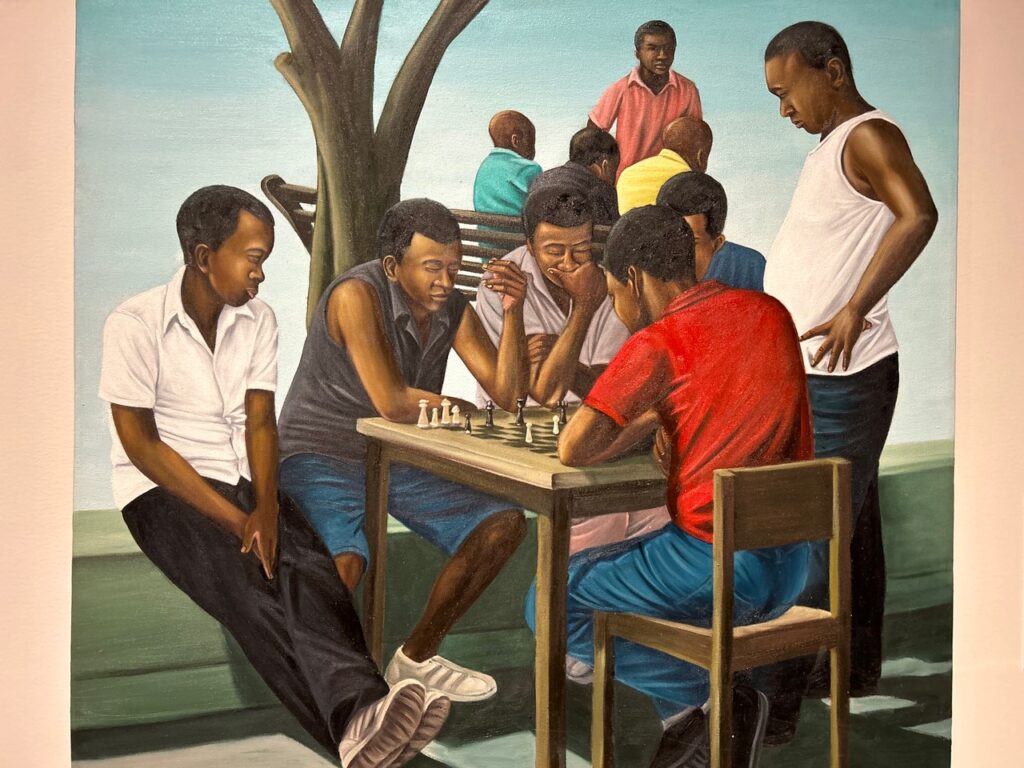

Other paintings depict the game being played. One an American scene painted by George Whiting Flagg about 1836. A white man and woman play while an African-American woman, likely enslaved, looks on. In another, painted by Congolese artist Zemba Luzumba in 2014, a group of young African men gather around chess games, an image meant to subvert the stereotypes about African men.

While the connections are often obvious, sometimes that’s not the case.

As in other previous exhibits, a signature piece from the TMA’s collection makes an appearance. South African artist Mary Sibande’s “Rubber Soul, Monument of Aspiration” depicts a domestic worker in a moment of jubilation.

This represents the concept of elevation in chess where a pawn can move to the end of the board, and be transformed into a more powerful piece. The woman shown has the hat and apron of a domestic worker, but is dressed in “the beautiful regalia” of the upper class. Her jump shows “her promotion from a domestic worker to a person of power,” the curator said.

Museum Director Adam Levine said it’s part of the museum’s strategy to place these pieces in special exhibits, so when visitors come back after the show has closed, they will see the familiar work in a broader context.

“Strategic Interplay” was organized by the TMA. Levine said the museum’s most recent shows have all been organized by the TMA itself or in collaboration with other institutions.

That’s possible by the increase in the number of curators. Those “knowledge workers,” he said, are able to create exhibits such as this that are “compelling and show unique scholarship.”

The show is yet another example of the museum’s broadening its scope of looking at art history. That included “Ethiopia at the Crossroads,” which closes today.

The museum has the resources to acquire new masks both through its trust, increased donations, and the funds brought in by selectively selling pieces from the collection.

“Strategic Interplay” engages visitors using a set of cards by encouraging them to move through the Canaday in a manner simulating a chess piece, maybe a queen, a bishop, or a rook. Each approach should give the viewer a different angle on the exhibit. Regardless of the path they take, experiencing “Strategic Interplay’ will end in victory.