By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

When trumpeter Kevin Cobb takes the stage with the American Brass Quintet next week it won’t be the first time he’s played brass chamber music in Bowling Green.

The Bowling Green native got a chance to play with the Tower Brass as a teenager. His teacher was Marty Porter, a member of the quintet.

Now he’s returns as a member of one of the world’s most esteemed brass ensembles. The American Brass will be in residence at Bowling Green State University Wednesday, Sept. 20 through Friday, Sept. 22. The ensemble’s visit will be capped with a free concert in Kobacker Hall Friday at 8 p.m. The visit is part of the Hansen Musical Arts Series.

Cobb, 46, joined the 57-year-old ensemble in 1998. The American Brass sets itself off from more popular quintets, the Empire and the Canadian, by its dedication to playing only music written for brass in five voices, Cobb said.

Early on, he said, there was “a split” between members who wanted to play ragtime and other accessible forms, and those who wanted to focus exclusively to brass quintet repertoire. The latter faction won.

That means it plays early music and contemporary music. From the beginning, the American Brass has been active in commissioning music by new composers.

The ensemble also sets itself apart by using a bass trombone, not tuba, as its lowest voice. The founders felt that the bass trombone’s lighter sound was more akin to the sound of a cello in a string quartet and was truer to the textures of early music that was scored for three trumpets and two sackbuts.

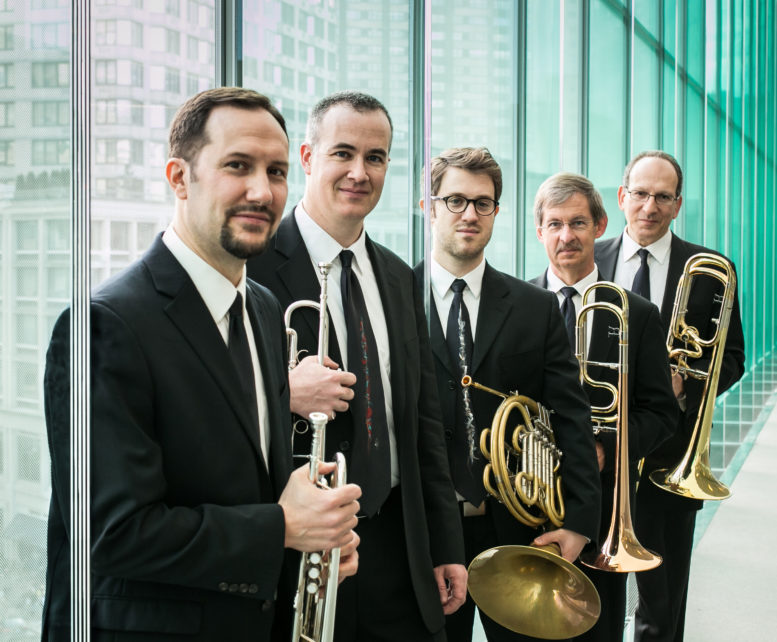

John Rojak is the bass trombonist. Other members are Louis Hanzlik, trumpet, Eric Reed, horn, and Michael Powell, the most senior member, trombone.

“For our group, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts,” Cobb said. “We’re not trying to showcase the French horn or bass trombonist.”

That was true the first time he heard the quintet. He and a friend were discussing the concert and then realized: “We’re talking about the music, not the playing.”

Cobb continued: “That’s what our musical mission has always been … trying to make the ensemble greater than the individuals.”

The musicians also understand that the contemporary music they play isn’t what audiences necessarily listen to at home. “People don’t know what to expect, and it’s our job to introduce them,” he said. “We believe in it and that comes across in our playing. We don’t program anything we feel half-hearted about. We’re advocates for every one of the composers we play.”

They always talk to the audience. “Having an introduction to it is very helpful.” They do this “without dumbing it down.” That may include playing excerpts to give listeners a sense of the sonorities they will hear in a work.

They’ve added many important pieces to the brass quintet repertoire including work by William Bolcom, Elliott Carter, Eric Ewazen, Gunther Schuller, William Schuman, and Joan Tower. The quintet maintains a list of composers they’d like to have pieces from, and approach them as funding becomes available. Juilliard and the Aspen Festival, the group’s summer home, have helped in this respect.

The business of commissioning work and other aspects of the musical enterprise will be among the topics the members will discuss during their residency. They’ll also talk about how to make a living as a musician.

“I’ll say this about life in music,” Cobb said, “it’s so varied. You really can (make a living) if you’re smart and resourceful and willing to rough it for a while. You can find avenues to pursue music in a lot of different ways, ways that are not necessarily taught to you in school.”

For the musicians in the American Brass Quintet, the ensemble is a small, but the most important, slice of their lives as musicians. “Because we don’t have the pressure on the group to be full time financially, we can afford to play the music we want, music we believe in.”

Cobb is an active freelancer who plays with the ensembles around Lincoln Center—the New York Philharmonic, the Metropolitan Opera, and the New York City Ballet – as well as teaching at SUNY Stony Brook, Juilliard, and New York University.

The son of Danielle and the late Thomas Berry Cobb, Cobb said his life was shaped by Bowling Green. “I had a great childhood.”

Bowling Green offered opportunities and diversity that belied its rural setting. He started studying music at 7 at BGSU’s Creative Arts Program. He wanted to learn either guitar or drums, and his parents decided guitar would be best. He liked it, but “it was a lonely instrument.”

So when it came time to select a band instrument, he was torn between trumpet, which it he was able to get a buzzing sound out of, or drums. Trumpet it was, he parents said. “I’m sure I would have been a great drummer,” Cobb says now.

He started taking lessons with Porter. “He’s always been a wonderful influence in my life. I don’t say it lightly that I owe him everything. I loved my lessons with him.”

That’s why he switched from classical guitar to trumpet. A great teachers can be such an inspiration, Cobb said, “that you have to blame them for your career.”

Bowling Green was a supportive environment. He remembers playing a jazz ballad solo in junior high, and percussionist Wendell Jones heard it. Jones put together mix tapes featuring all the great jazz players, including Louis Armstrong, Clark Terry, Don Ellis – a particular favorite of the young Cobb’s, and Maynard Ferguson.

A Ferguson show was the first trumpet concert Cobb remembered going to, and the Canadian brassman’s high note antics had him back at home trying to squeak out the highest notes he could.

He said he was also fortunate enough to hear cellist Yo Yo Ma, flutist Jean Pierre Rampal and other Festival Series guest artists. The more he got into music, the more he felt different from his peers.

At 13 his parents sent him for eight weeks at Interlochen Arts Camp in Michigan. He remembered the first week being dreadfully homesick, missing his parents and his dog. But “pretty quickly I realized this was great. I was with kids who were as enthusiastic about music as I was, kids from around the world. Then my life really changed. It was difficult to think about going back to normal life.”

He spent two summers at Interlochen, and then after attending St. John’s for his freshman year in high school, he transferred to the Interlochen Arts Academy. His biggest regret, he said, was not being able to study with Porter.

After graduating from there, he attended the Curtis Institute of Music and then Juilliard for graduate studies.

He settled into music. Though he had his sights on getting an orchestral job, he found he picked up jobs of all sorts here and there. “Before you know it, you pay for groceries at the end of the month.”

Being a professional musician is challenging. “It’s not for the faint of heart.”

But he still plays guitar for fun. “Every musician started for the same reason: to have fun with it. When you get to be a professional, it changes your relationship to the instrument and it’s not fun. Having that secondary instrument as a hobby maintains that fun aspect.”

And “I still love sitting down and getting better on the instrument – the art of practicing on an instrument and trying to get better. As long as that’s still there, I’ll keep going.”