In the Toledo Correctional Institution, Rufus Bowman keeps his two rescue inhalers and hand sanitizer close.

He has severe, chronic asthma, leaving him especially vulnerable to COVID-19. As the new coronavirus that causes the disease continues its steady penetration of Ohio’s prisons, Bowman’s wife is terrified.

“This is a death sentence to these people,” said Chazidy Bowman, Rufus’ wife. “This is a real-life death sentence. They’re like a bunch of cows waiting to go to slaughter.”

With prison caseloads adding up, advocates for prisoners say the jails are outbreak clusters waiting to happen, endangering the state’s 49,000 inmates.

A union representing prison workers, meanwhile, says Gov. Mike DeWine’s administration’s response has been spotty, leaving nearly 11,000 prison workers at risk of infection.

“It’s become a Facebook meme — we’re not essential, we’re sacrificial. That’s the feeling of people right now,” said Chris Mabe, Ohio Civil Service Employees Association (OCSEA) president.

As of Tuesday afternoon, 14 Ohio prison inmates have tested positive for the disease. Twenty-three more tests are pending. This comes from a narrow pool of 72 inmates total who have been tested.

Meanwhile, 27 prison workers have tested positive for COVID-19.

Five prison facilities in Franklin, Marion, Pickaway and Toledo counties are in institution-wide quarantines, effectively locking down nearly 7,500 inmates.

On Monday, DeWine temporarily dispatched 26 medical workers with the Ohio National Guard to assist at Elkton Federal Correctional Institution in Columbiana County. Three federal inmates have died there in connection with the virus, and seven inmates have tested positive. He said dozens are showing symptoms.

“There is no doubt that this prison needs help,” DeWine said.

On Tuesday, DeWine recommended (but did not order) the release of 167 prisoners meeting narrow criteria. Of them, 141 are within 90 days of release on crimes that are not sex offenses, homicide, kidnapping, abduction, ethnic intimidation, terrorism or domestic violence. They also have no prior incarcerations, have shown good behavior in jail, and have not been denied judicial release.

The other 26 are aged 60 and up, have chronic health conditions, are at least halfway through their sentence, and meet many of the same criteria as the larger group. Tuesday’s release recommendations come after similar recommendations of release for another 38 prisoners meeting a narrow criteria.

Rufus Bowman, 25, began a nine-year sentence in October 2014 after being convicted of aggravated robbery and felony assault.

Chazidy Bowman said since he’s been incarcerated, Rufus Bowman has earned his GED and is finishing up an associate degree. His full sentence ends in 2023, but she says the degrees and good behavior could count toward an early release.

She described him as intelligent, articulate, funny, and inquisitive.

“He loves my kids, my kids love him,” she said. “He’s a dad when he’s never even really had one. It amazes me how he has a way with them. He’s patient, he’s very kind, and he’s very humble.”

She said Rufus Bowman and others need to be released so they don’t die in jail on the tail end of their sentences.

Prison staff

It’s not just prisoners who are scared. Mabe, of OCSEA, criticized DeWine and Ohio Division of Rehabilitation and Corrections Director Annette Chambers-Smith for restricting prison workers’ sick leave and flip-flopping on their rights to wear personal protective equipment (PPE).

A federal law passed in response to the pandemic requires employers to provide two weeks of paid sick leave. DRC, however, claimed an exemption to the provision.

“It’s a disincentive,” said Sally Meckling, a union spokeswoman. “If you’re trying to incentivize people to stay home, and the federal leave is available and it’s free, meaning the feds are going to pay for it, then why exempt DRC employees who obviously can’t telework?”

Likewise, DRC initially forbade its employees from wearing PPE. It then briefly allowed them to if they signed a waiver. Now, it is allowing workers to wear masks, but Mabe says the agency is not providing them.

DRC spokeswoman JoEllen Smith did not respond to inquiries regarding why the organization restricted sick leave. She said Ohio prisoners are making PPE they wear, and prisoners and staff will be provided PPE “if the facility is able to obtain the mask from an external source.”

When asked at a Tuesday press briefing, DeWine did not answer whether prison employees are being provided PPE.

Late last month, an inmate at Belmont Correctional Institution who says he’s HIV positive took to the Ohio Supreme Court seeking release.

He argued his autoimmune disorder coupled with the outbreak turns his 30-month stretch into a death sentence.

The ACLU of Ohio filed an amicus brief on the inmate’s behalf. In the court filing, Cleveland State University professor Meghan Novisky, provided a statement declaring that between poor hygienic conditions, shared spaces and overpopulation, Ohio prisons could become a COVID-19 epicenter.

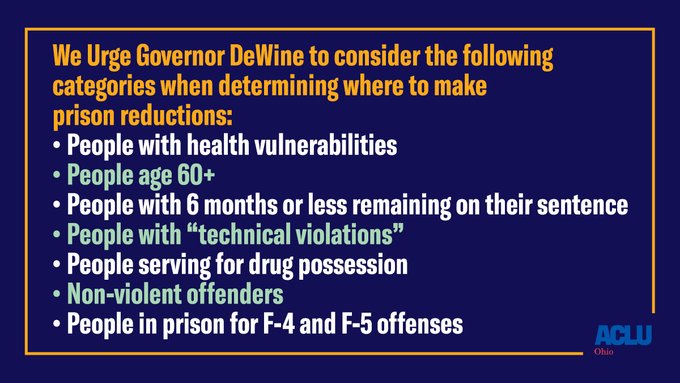

“If serious action is not taken swiftly, Ohio’s prisons will soon be hotspots for COVID-19, with many staff and incarcerated individuals infected and facing elevated risks for medical complications and mortality,” she said.ACLU of Ohio✔@acluohio

.@GovMikeDeWine our prison pop is already over capacity by about 10K people. Releasing 10K people would still make our prisons at 100% capacity.

THE ONLY WAY TO EFFECTIVELY ADDRESS COVID-19 IN PRISONS IS TO RELEASE LITERALLY THOUSANDS OF PEOPLE. (Not 204.)

We have a plan!

22Twitter Ads info and privacy19 people are talking about this

Gary Daniels, a lobbyist for the ACLU, put it bluntly.

“Mass incarceration is totally unequipped to deal with something like this,” he said.