By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

When he was 6 years old, Donovan X. Ramsey had his first bicycle stolen by a crack addict.

The man, who was a familiar figure in neighborhood took it away saying he would fix it. Young Donovan waited. The man never brought it back.

When Ramsey, who lived in Columbus, told his mother, she was furious. “You gave your bike to a crack addict.” Young Donovan did not get another bike.

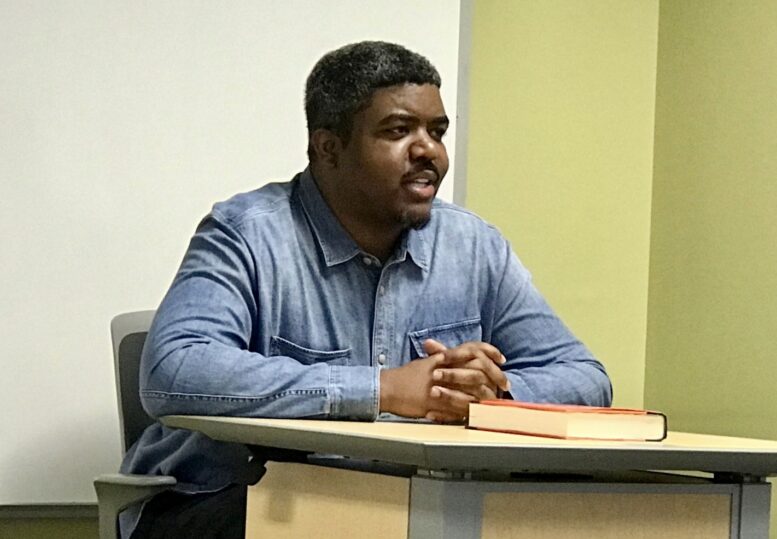

“We carry little things with you,” he told students at BGSU during a recent visit to campus.

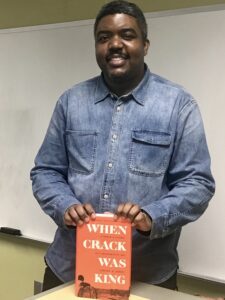

Ramsey, now 36, ended up writing a book on the crack epidemic. “When Crack Was King: A People’s History of a Misunderstood Era.” tells the story of those times through the eyes of those who lived through it and survived.

Ramsey was on campus to deliver the Florence and Jesse Currier keynote as part of Spotlight on Journalism and Public Relations hosted by the School of Media and Communication.

Earlier in the day , he spoke with a class on diversity issues in the media taught by Ewart Skinner.

Ramsey said as a Black journalist he has always been interested in telling the stories of Black people. He has a particular interest in how African Americans are treated in the criminal justice system. “I spent a lot of time in prisons,” he told the class. “The topic of the crack epidemic came up constantly.”

This is what brought about the system of mass incarceration.

“People were afraid,” Ramsey said. “They wanted to problem ended. This was their truth. So, they created this tool to basically lock everybody up. … We moved into a period of mass incarceration.”

Other solutions such as treatment and decriminalization were not considered by the powers-that-be.

The story, he realized, required the scope of a book. Working with an agent, he put together a proposal – a sample chapter and an outline. He ended up with a contract and an advance from Penguin Random House. The book is published on its One World imprint.

He used the advance to travel to large cities around the country talking to drug counselors, businesspeople, politicians, and activists.

Ramsey said he found these people through connections in their communities. When he arrived in a city, he would use Google maps to find beauty parlor, barbershops, nail salons, places people gathered and talked. He said he was writing a book about the 1980s and 1990s.

The people who he was drawn to, he said, were good talkers. “People who would give me good quotes.”

More than that, he wanted people, who had thought deeply about their lives, and were introspective.

Interviewing, he said, is his favorite part of his work, though that was “the part of the job I was most nervous about when I started out.”

His background in psychology, which he majored in at Morehouse in Atlanta, helps when he has to ask somebody “why they made bad choices.”

Ramsey did not set out to be a journalist. He wanted to be a lawyer. But before his senior year, he interned in a law firm and discovered he didn’t like it.

He consulted with a psychology professor, who was his mentor. Turns out the professor had done a stint as a journalist early in his career. Given Ramsey was an editor on the college newspaper, he suggested he may explore that. The professor eventually wrote Ramsey a letter of recommendation to Columbia.

Before going to Columbia, though, Ramsey tried his hand as a freelancer. He struck out. “I was broke,” he told the students.

Ramsey went to Columbia in New York City because he wanted to be where the publications he wanted to see his words in were located. It was fruitful ground to explore his interest in criminal justice with the largest police department in the world.

First, though, he got a job at Money. His editor didn’t like him. The feeling was mutual.

Ramsey advised students against taking such a job. “If you take a job not doing the kind of work you want to do, you just get more opportunities to do more of what you don’t want to do.”

He did go on to do what he wanted to do: writing and reporting stories for The New York Times, The Atlantic, GQ, WSJ Magazine, Ebony, and Essence, as well as being a staff reporter at the Los Angeles Times, NewsOne, and TheGrio.

That led to the book project.

While he’s concerned that social media overloads people with information, he’s optimistic that people still crave long-form narratives. “There will always be people who want to read a story like this.”

The crack epidemic tapered off in in the first years of the 1990s. The younger generation did not take it up, though other drug scourges, meth and now opioids, each with its own dynamics.

But the scars of the crack epidemic remain in neighborhoods and in the prison system.

In an exchange with student Ikera Ike, who like him grew up in Columbus and is involved in housing issues, he admitted it was hard for him to return to his hometown.

When he was a sophomore at Morehouse, his mother moved down to Atlanta. His father lived in North Carolina.

When he comes back to Columbus, he finds neighborhoods decimated by the decline of industry and the crack epidemic. Other neighborhoods, once occupied by working class families, are now flourishing because of gentrification. The houses cost as much as $500,000, Ike said. And high-priced coffee has replaced crack.