Last year saw the highest numbers of fatal overdoses, gun deaths, homicides, and motor vehicle fatalities among Ohioans over the last 15 years, according to data from the state health department.

It was also the third-worst year on record for suicide deaths of Ohioans, just off the high mark set in 2018.

Taken together, the data adds detail to a troubling trend of a 51% increase in deaths of working age Ohioans over the last 15 years. The mortality falls into the category of what sociologists call “deaths of despair” — often indicators of larger ills around economics, access to health care, economic and geographic mobility, racial inequalities and other complex societal problems.

The data is from the Ohio Department of Health’s mortality database, which tracks deaths from 2007 to the present. It doesn’t include historical data, which would show much higher rates of car crashes and homicides around the 1960s and ’70s.

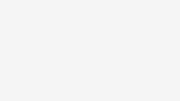

In 2021, some 5,395 Ohioans fatally overdosed, more than tripling that figure 15 years ago. By state, Ohio had the fourth highest rate of fatal overdoses per capita the year prior, according to the CDC.

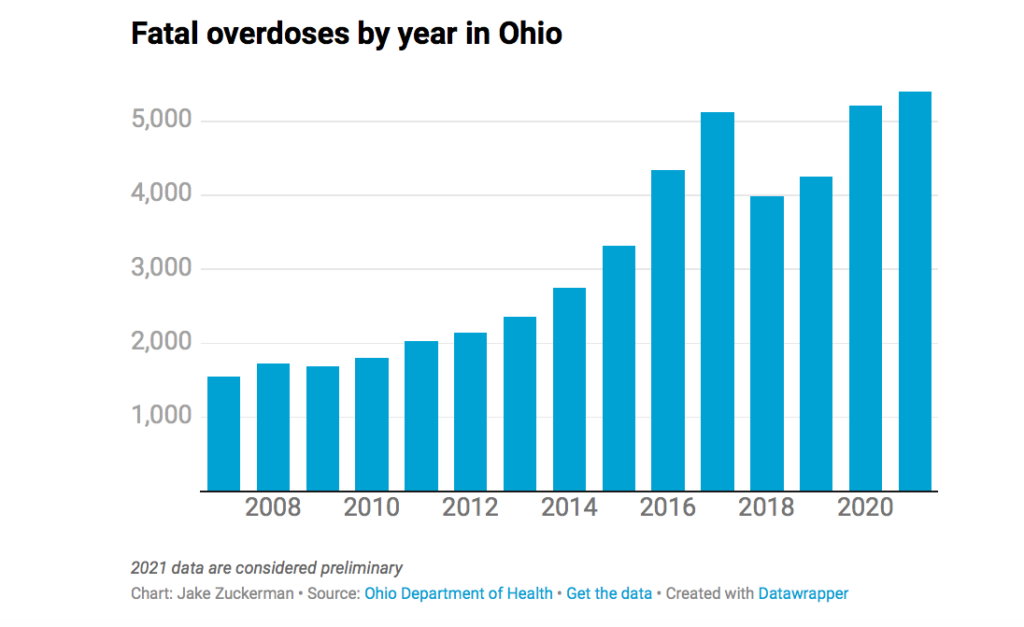

Also in 2021, 1,909 Ohioans died by gunshot. This is the fourth year in a row of new record gun deaths in the state. The trend was driven in part by a record number of homicide deaths (1,018). Conversely, suicides comprised a lower percentage of gun deaths in 2021 (53%) than in years past.

Ohio has drastically loosened its gun laws in recent years. Republican state lawmakers passed legislation in 2020 removing the legal duty to seek retreat before shooting to kill in perceived self-defense. They passed legislation this year removing training and background check requirements to carry a concealed weapon. They also passed legislation allowing teachers to carry firearms in the classroom after receiving certain training.

Some 1,455 Ohioans died in motor vehicle crashes in 2021, another new record for the recent era.

The Ohio data follows national trends of record numbers of homicides, unintentional drug overdoses, gun deaths and fatal crashes between 1999 and 2021, according to CDC data shared by the state health department. The year also saw the second highest number of suicides nationally in the same time frame.

What to make of it?

Several public health researchers and policy analysts weighed in on the mortality data.

Greg Moody, the point man on health policy for GOP Gov. John Kasich’s administration and now an Ohio State University professor, said Ohio has seen some its progress against deaths of despair erased.

Solutions are as complicated as the problem, he said. They must address economics, racial and economic inequality, political underrepresentation, wage disparities, pre-existing health conditions, untreated mental illness, and others.

“COVID hit and the real issue became clearer to more people – differences in opportunity related to wealth and race directly impact health outcomes,” he said. “Wealth and race are correlated to the likelihood of exposure to COVID on the job, job loss, exhausted savings, preexisting conditions, access to care – when these change for the worse, so do overdoses, accidents related to alcohol, gun deaths, homicide, suicide, also heart disease, stroke, untreated mental illness, and others. Until we address the root causes, everything else is a trip to the emergency room.”

Amy Bush Stevens, vice president of the Health Policy Institute of Ohio, said the deaths seem to be pointing at problematic trends in society more generally.

“One thing that’s particularly troubling is that these causes of death are largely preventable,” she said. “There are effective things that we can be doing to reverse these.”

Some solutions are available, she said. These include expanding Ohio’s good Samaritan laws, which shield people from criminal consequences if they assist others who overdose on drugs; expanding access to naloxone, which reverses drug overdoses; or doing the same for test strips to look for the presence of fentanyl or other synthetic opioids.

Other HPIO research has shined light on similar problematic data points. For instance, firearms have become increasingly prevalent in suicides since 2007; suicides among young Ohioans have increased since 1999 but the trend is most pronounced among young, Black Ohioans; and chronic liver disease, which is linked to alcohol use, increased 74% since 2007.

Dan Flanney directs the Begun Center for Violence Prevention Research and Education at Case Western Reserve University and has studied overdose trends in Cuyahoga County. He said the increase in overdoses is likely driven by synthetic opioids like fentanyl or carfentanyl that are increasingly prevalent in the drug supply.

“The last couple years have been nasty across the board with respect to gun violence and overdoses in particular,” he said.

In Cuyahoga County, he said about two in three people who fatally overdose have three or more substances in their system. That could either indicate a person intentionally using multiple drugs, or a tainted supply.

He has joined calls for a public health approach to gun violence, offering an eight-point plan to do so. Several points it calls for like bans on large capacity magazines, red flag laws, safe storage requirements, and others have proven to be non-starters in the Republican-controlled state legislature.

The National Highway Transportation Safety Administration researched the pandemic-era increase in traffic deaths. It found drivers are increasingly engaging in risky behaviors like speeding, driving under the influence, and skipping on seat belt use.

Dennis Calhoun runs Harm Reduction Ohio, which advocates for policies like needle exchange programs aimed to reduce the risk of drug use. He said the trendlines all seem to point back to the pandemic in one way or another. He noted that patterns like overdose and gun death increases are occurring nationally as well.

Regarding fatal overdoses, he argued one key driver is closures at the U.S.-Mexico border. Those closures, he said, choked off the heroin and cocaine supply. This left a hole in the market that wound up being filled by synthetics like fentanyl.

Political responses

The Ohio Capital Journal shared the data with several state agencies and the two candidates running for governor.

Dan Tierney, a spokesman for Gov. Mike DeWine, said the ODH data confirms nationwide public health trends. And he noted that in the last 12-month period for which CDC data is available, Ohio has experienced a decrease in overdoses — a positive indicator only shared among seven other states.

DeWine, he said, has advocated for mental health, addiction services, and law enforcement responses. He has also called for legislation aimed to restrict cell phone use of drivers, as well as stiffening penalties for violent offenders.

He pushed back on drawing a line between the governor’s gun policies and the recent rise of gun violence.

“We do not see where the specific changes regarding concealed carry permits and school districts’ option for authorizing certain staff to carry in a school safety zone would affect homicide or suicide rates,” he said. “Concealed carry permits have generally been used by law-abiding citizens, and those barred from carrying are barred from having concealed carry permits.”

Nan Whaley, a Democrat running against DeWine, said in a statement that DeWine is more focused on pursuing an “extremist agenda” than tackling problems that have worsened under his watch. And the surge in gun deaths, she said, is unsurprising.

“Unfortunately, because of his inability to stand up to the extremes in his party and his gun lobby campaign donors, it will only get worse,” she said. “Legislation he has signed like permitless concealed carry and stand your ground have been proven to make communities less safe. Between the troubling data on gun deaths to fatal overdoses, it’s clear that Ohio is certainly worse off under Governor DeWine’s leadership.”

Ken Gordon, a spokesman for the Ohio Department of Health, said one of the agency’s most important roles is surveillance to raise awareness and target resources. He also cited several ODH programs aimed to expand mental health screenings; funding for school-based health centers, some of which include behavioral health services; increasing availability and awareness of naloxone; and a program that has trained doctors to screen some 230,000 patients for opioid-use disorder, which have linked more than 7,000 to relevant health services.

Spokesmen for the Ohio Department of Public Safety and the Ohio Department of Jobs and Family Services didn’t respond to inquiries.