By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

When Yayoi Kusama was a child she experienced hallucinations. Large polka dots filled the rooms of her house. Violets had faces. Her dog spoke to her in human speech, and she responded with barking.

Kusama would retreat to her room and try replicate the experiences in drawings and paintings. It was the only way she could deal with them.

In her autobiography, “Infinity Net,” she wrote: “Recording them helped to ease the shock and fear of the episodes.”

She didn’t tell anyone, especially, not her mother. Instead she was seen as a “unmanageable, useless child.”

But in time those hallucinations blossomed into an international art career. In the 1960s her fame rivaled Andy Warhol’s.

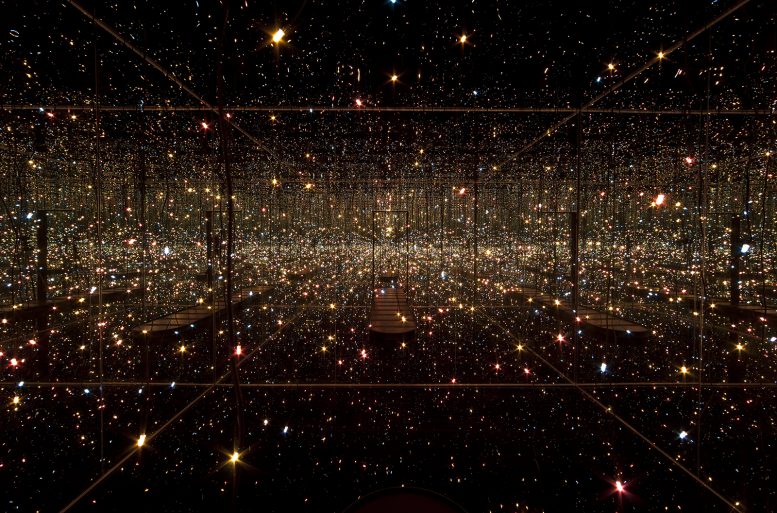

Local art lovers will have a chance to immerse themselves, if only for a literal moment, in the hallucinogenic world of Yayoi Kusama, through the installation “Fireflies on the Water,” opening Saturday, Dec. 14 in the Toledo Museum of Art’s Canaday Gallery.

Using lights and mirrors, Kusama creates an infinite space. The viewer steps onto a platform that extends into that world. Above, is a sky of unfathomable clarity. Around the viewer is a dense thicket, growing thicker as it extends into space. Below is water, that plunges into a great depth.

The viewer is placed within an other-worldly, floating environment, their reflections likes specters within the tangle of lights.

After being let into the room, each viewer has but 60 seconds, then the door opens. And they are ushered out. Another visitor takes their place.

That’s the way the artist wants it, museum officials explained.

In “Infinity Net,” Kusama wrote about her installations: “The rooms gave such pleasure that people would enter and not want to leave.”

Only one person is allowed in at a time — this is solitary experience. (Exceptions are made for those needing help physically, and for children.)

“Fireflies” is the most recent immersive exhibit at the Toledo Museum. Those include Gabriel Dawes’ light piece “Plexus no. 35,” Rebecca Laws’ hanging garden of dried flowers and plants, “Community,” and currently Anila Quayyum Agha’s cut metal sculptures lit from the interior, “Between Light and Shadow.” These turn the “viewer” into an element of the art.

These appeal to many in the museum’s varied population of visitors, said Lauren Applebaum, a leadership fellow at the museum.

They also invite social media engagement, expanding their resonance beyond the museum’s walls.

Applebaum said museum officials were considering “how to activate” the Canaday Gallery. Through John Stanley, the museum’s interim director and retired chief operating officer at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the New York institution loaned the TMA the installation.

“Fireflies on the Water” is also another instance of the museum presenting work by artists, from a variety of ethnic backgrounds and gender identities.

“The museum is really trying to diversify with multiple voices,” said Stephanie Elton, the museum’s director of communications.

There’s a refreshed display of Native America art and the continuing exhibit Global Connections. Agha is a Pakistani-American woman.

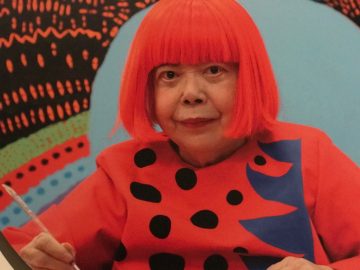

Kusama is female, Japanese, and suffers from mental illness. By choice, she has lived for decades in an institution for the mentally ill maintaining a studio nearby where she works.

“I would say the hallucinations she’s experienced ever since she was a child have had an impact on all Kusama ’s art work,” Applebaum said. “The infinity rooms are really the pinnacle of that vision. It is so immersive and such a kaleidoscopic experience for visitors to be inside these visions.”

Kusama grew up in an ancient feudal family. Her family traded in seeds.

Her mother did not support her desire to be an artist. She would sometimes destroy the art her daughter made and refused to buy her supplies.

Kusama would use what she could scrounge, and sometimes steal. Her father, a spendthrift, would sometimes lavish her with supplies, she recalled in her autobiography.

Her mother would send her out to spy on her father when he slipped away to meet other women.

When she reached her teenage years, her mother plied her with the prospects of an arranged marriage to the most eligible bachelors in the region.

She rejected them all. Kusama said she was “terrified of sex.” She later addressed this revulsion by making thousands of soft phalluses, used in her first installations. “By continually reproducing the forms of things that terrify me, I am able to suppress the fear,” she wrote. Lying down among them, she continued, “turned them into something funny, something amusing.”

This was after, on the advice of Georgia O’Keefe, she had moved to New York and became one of the leading lights in the Pop Art movement, as well as the counter culture.

Kusama became notorious for the happenings she staged, on Wall Street, outside a cathedral, and other public locations. These highly charged experiences involved nudity and sex.

She returned to Japan in 1975, where she has lived since, continuing to produce work that opens up vistas that refuse to remain trapped within her imagination.

***

“Fireflies on the Water” will be on exhibit at the Toledo Museum of Art through April 26. Tickets are required, and are $5 and free for museum members from tickets.toledomuseum.org.