By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

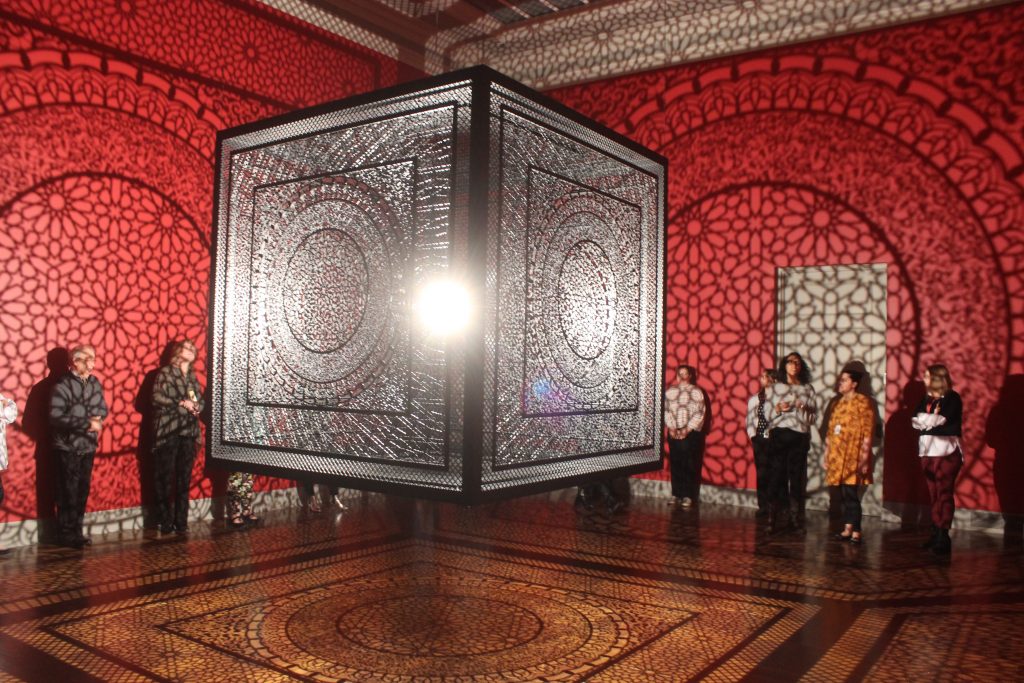

If Anila Quayyum Agha’s pierced metal sculpture “Intersections” fell on someone it could do serious damage.

It would turn you into very nice minced meat, the artist quipped.

Yet at the press briefing that didn’t keep a couple journalists from crawling under another piece consisting of two suspended geometric shapes, to view it from a different angle. That’s a testament to how captivating the work is.

Suspended from the ceiling of gallery 5 at the Toledo Museum of Art — “Intersections” seems to be floating.

Inside is a brilliant light that tosses shadows throughout the room, and tattoos the designs on the faces of viewers.

The viewers become part of the work. Agha hopes by being immersed in the work, they will absorb the meanings at the heart of these physical metaphors.

“Anila Quayyum Agha: Between Light and Shadow” opened this weekend at the Toledo Museum of Art. The exhibit remains on view through Feb. 9. Tickets are $12 and free for members. Visit tickets.toledomuseum.org.

This is the first time so many of her large scale works have been exhibited in one museum, said Diane Wright, Toledo Museum of Art curator for the show.

Agha, 54, first emerged on the scene in 2014 when a version of “Intersections” was shown at ArtPrize in Grand Rapids, Michigan where won both grand prize determined by the jurors as well as the popular choice award.

The original of the 6.5 foot cube was made of plywood, she said. The choice of material determined by cost.

Now working with her husband, Steve Prachyl, the panels are cut at factory based on Agha’s designs. Prachyl does the fabrication of the work.

Originally, he said, she did the designs by hand but now uses computer-assisted design technology.

She considers “Intersections” as her “flagship” piece.

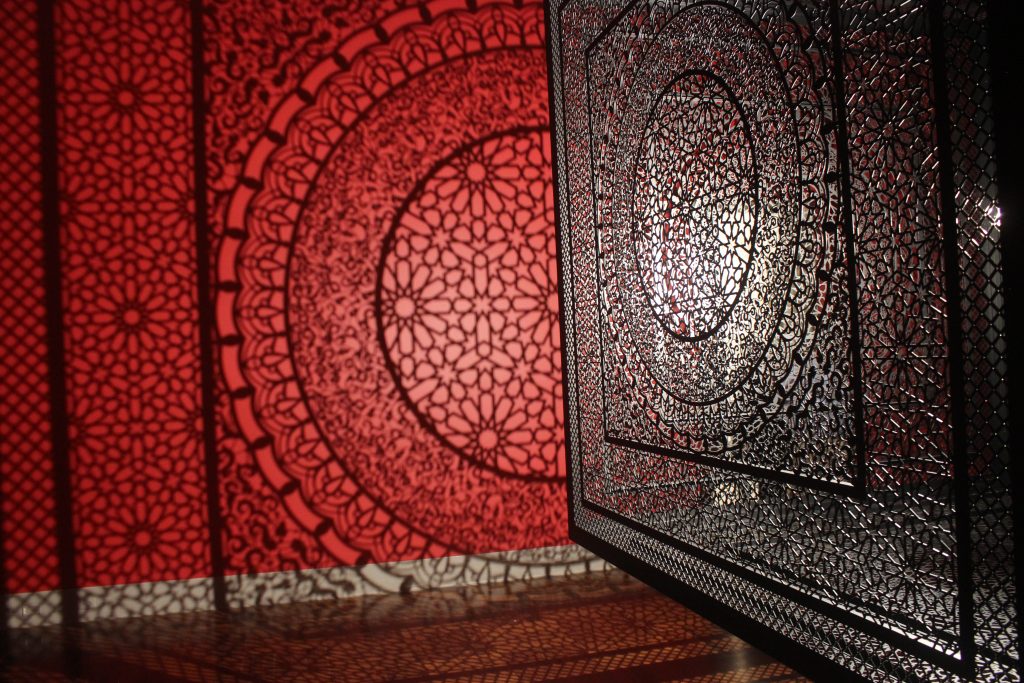

Having the work in metal plays up the contrasts inherent in her conception — the metal is heavy but presented as if weightless. The light inside is intense, yet the shadows cast are soft.

She begins with imagery “appropriated” from Islamic culture, said Agha, a native of Lahore, Pakistan, who immigrated to the United States when she was in her twenties.

She then redesigns those patterns “to fit my new paradigm.” That reflects the shifting of cultures in a world entangled in social media.

The three pieces on exhibit reflect her own position as an immigrant, her worldview is a product of both her current and former homelands. The room is suffused with that imagery.

She hopes this gives the viewers a sense of who she is, and what she believes the world needs.

“The biggest thing that’s important for us is empathy and belonging,” Agha said. That becomes all the more important as the world faces the dangers posed by climate change.

“I’m concerned for my child. What’s he going to face as he grows older? What are we leaving for him?”

Increasingly severe weather caused by climate change also factors into the flood of refugees.

“This Is Not a Refuge! 2” directly addresses that crisis. The patterns on the house-shaped structure are adapted from traditional designs found on book rests that hold Korans. Agha modified them to emphasize how they swirl evoking the wind and objects caught up in it.

“It’s the idea of the elements, the winds, the cyclones, that we see affecting people on an elemental level,” she said. The refugees have been cast adrift, and if they were to return home “they may die.”

In the background, a recording of refugees speaking about their experiences plays.

The third piece, “The Greys In Between,” is composed of two geometric forms, one small, one large.

Each piece impacts the other, the light from one casting shadows from the other. This reflects, the artist says, the way people, or even cultures interplay. One may be larger, but it is still subject to the influence of the smaller body.

Agha said she was in fourth or fifth grade when she realized her calling as an artist. She was in boarding school north of Islamabad and a visiting teacher had them paint watercolors.

Agha remembers looking out over the valley, and painting that scene.

The teacher declared that she would be an artist.

Agha had no idea what that meant, but now knew what she wanted. Her mother was concerned about how she would earn a living. The compromise was that she would study textiles.

Agha continued to work in textiles, and did her graduate work at the University of North Texas in fiber art.

This was good grounding, she said, because it involved several disciplines — design, screen printing, drawing, stitching.

In 2010, she visited the Tate Museum in London when it was showing Olafur Eliasson’s “Big Sun.”

The work had a large sun on one end of a gallery. The walls were covered with mirrors.

That exhibit convinced Agha that she wanted to explore art that merged immersion with design. Her first venture was“My Forked Tongues,” in which she hung curtains of beads, cut paper, and metal designs.

It took Agha, who is a tenured art professor at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis, a year to hand string those objects.

It took her as long to create the original plywood “Intersections.”

This is the second major immersive show the Toledo Museum has featured in the past year, following Rebecca Law’s “Community.”

The power of immersion, Agha said, is “you can do multiple things for the viewer.”They experience the work from the artist’s point of view while also bringing their own point of view to bear. “They can marry the two together,” she said.

“The sensory experience stays with you,” she said. “You become part of the work. You become part of the moment.”