By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Starting the year at the Toledo Museum of Art has become a tradition for me and my wife.

It’s relaxing, and the food is good – even if because of COVID the dining room is closed so the sandwiches had to be eaten in the car. I get to revisit shows I’ve seen during press previews and written about.

That’s humbling.

I always notice details I wish I had, and should have, seen the first time. But a press preview is not necessarily the best way to absorb art.

That’s true even when the artist is giving a guided tour as : Judith Schaechter did at the October opening of “The Path to Paradise: Judith Schaechter’s Stained Glass Art.”

Sorry, the exhibit closed Sunday. I’m even sorrier for those who missed it after spending an hour in the gallery. At the preview, Schaechter was almost a distraction – self-effacing, with a wicked sense of humor, she kept us entertained. On Saturday though, her work did the entertaining, and I understood what I missed.

Her windows are built in layers, which gives them a depth, physically and emotionally. She turns the reverential medium of stained glass into a raucous exploration of the female psyche. There’s ecstasy and agony presented in a way that they are often hard to distinguish. All the deep-seated anxieties from childhood onward explode in cartoon expressionism. Exploring almost four decades of work, patterns emerge. Rocks appear in a number of pieces. They are ambivalent – they could be jelly beans, or Easter eggs, or pharmaceuticals, or maybe just colorful rocks. Her female figures are twisted and exposed, yet powerful. And flowers blossom, rendered in precise botanical detail, a testament to Schaechter’s craft.

Coming back to an exhibit, I find works I overlooked before. One was “Feral Child,” with a young female sleeping inside the pelt, including the sharp-toothed, gaping mouth, of a wolf. The image is a primal fairy, with swooping, sharp edged crows filling the winter sky. The figure vulnerable, yet at peace with herself.

Fantasy also infuses “Telling Stories: Resilience and Struggle in Contemporary Narrative Drawing.” COVID forced the cancellation of the press preview for the exhibit. Instead, the museum offered reporters individual tours with the curator.

The show features two fantasy worlds. One, imagined by Robyn O’Neil, is populated by men and that ends in ecological annihilation. Another, imagined by Amy Cutler, is populated by women, and their hair. One Cutler image shows how the hair from sleeping women is pulled and woven back into the heads of other women.

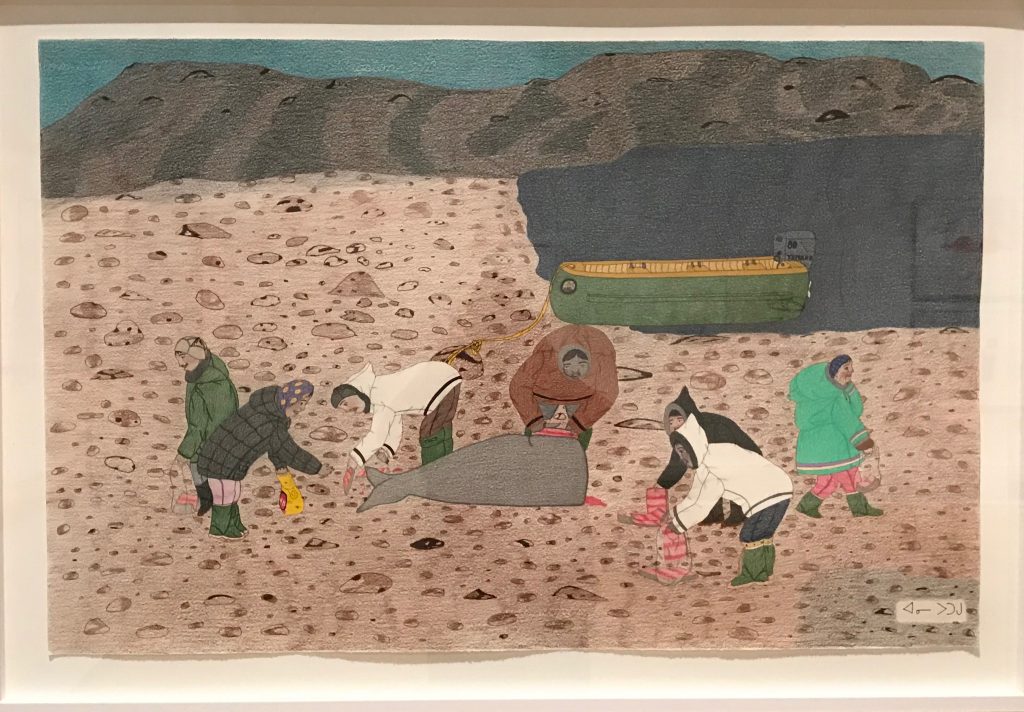

The third artist included in captures the reality of her Inuit community in the Canadian Arctic. Most of Annie Pootoogook’s drawings show the intersection of traditional life with contemporary life. On Saturday, though, I was fixated by a piece depicting an age-old scene that I overlooked during my first visit. “Women Gathering Whale Meat” is a striking image of women slicing and carrying away thick pink steaks from the carcass of a whale, a work at once ethnographic and expressive, and an interesting contrast to the nearby image of Inuit shopping in a grocery store.

These exhibits exemplify the museum’s determination to expand the canon beyond the domination of white males.

That’s especially evident in “Radical Tradition: American Quilts and Social Change.” The exhibit is designed to shatter the status quo. It stitches together a narrative from the abolitionist movement to battles that continue to rage. With the inclusion of two tour-de-force works, Besa Butler’s portrait of Frederick Douglass, “The Storm, the Whirlwind, and the Earthquake,” and Therese Agnew’s “Portrait of a Textile Worker,” it’s easy to miss other more low-key personal works like a self-portrait of a gay artist that uses vintage quilts. And facing Agnew’s “Portrait” is Sabrina Gschwandtner’s “Hands at Work,” which pieces together old 16mm film into traditional quilt patterns. Peering at the frames gives the sense of looking into lost worlds.

That these exhibits, as well as “Photo ID: Contemporary African American Works on Paper,” were featured during a time when the museum draws in steady stream of curious viewers is important. My observations led me to believe this was not the usual museum crowd. That they would visit and associate the institution with such challenging works is a step forward for the museum and its mission to embrace the totality of the world and its community.

Though the stained glass show is closed, “Radical Tradition” and “Telling Stories” continue through Feb. 14 and “Photo ID,” through Jan. 17.