By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

The artists, renown or anonymous, in “Radical Tradition: American Quilts and Social Change,” are fighting for social justice one stitch at a time. Quilts, so often a symbol of warmth and comfort, are also a tool to disrupt the status quo.

That’s the message of “Radical Tradition: American Quilts and Social Change,” an exhibit that opened last weekend at the Toledo Museum of Art. The exhibit continues through Feb. 14.

Lauren Applebaum, the associate curator for American art, assembled the exhibit from pieces spanning 170 years. She has been studying quilts, especially in relation to the Industrial Revolution.

She noticed contemporary artists were beginning to work quilts into their practice. Some were creating quilts while others were employing quilt-making techniques and merging them with other media and genres.

Some artists were returning to the form because it’s tactile, a reaction to the dominance of digital media. For many it is a disruption of the hierarchy that deems some media as high art while others are considered folk art.

“I noticed this consistent undercurrent that contemporary artists are using quilts and textile-based craft practices to raise awareness, express their opinions or call for some sort of social reform,” she said. “Of course, quilt making as always been used that way from time to time throughout history. I thought it would be interesting to place those contemporary works in conversation with historical examples.”

That’s especially apparent in the work that serves as a centerpiece of the exhibit, Bisa Butler’s “The Storm, the Whirlwind, and the Earthquake,” a life-size portrait of Frederick Douglass, rendered in silk, cotton, wool and velvet. Butler’s training as a painter is evident in the vivid portrayal of Douglass as a young firebrand advocating for the liberation of his people. The work was completed early this year, and purchased this summer by the museum. The title comes from his speech “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?’ delivered in 1852.

Nearby is a quilt made by anonymous New England abolitionists a year or so before Douglass delivered that speech. The quilt speaks to the hope that all states will be free states, something it took the trauma of civil war to achieve.

The ongoing struggle for racial justice is reflected in other works. When those who participated in the Selma March lost their jobs because of their activism and insistence of exercising their right to vote, Estelle Witherspoon helped found the Freedom Quilting Bee. The quilts produced provided a source of income.

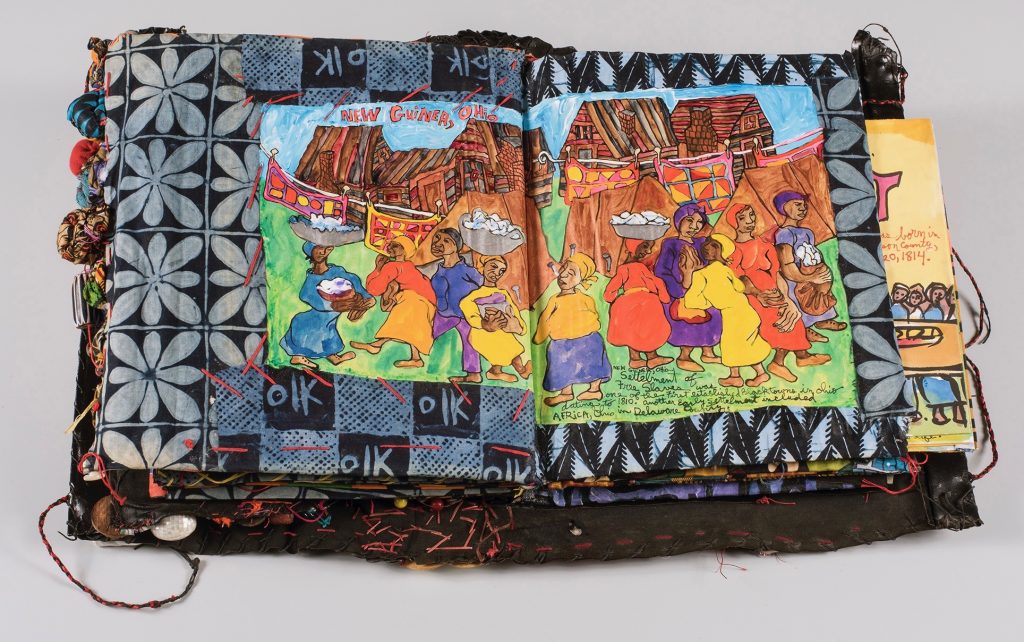

The Ragmud Series: Volume 8, Slave Epics (TMA Image)

One of her quilts “Housetop” is included as is one of the textile books by Aminah Robinson. In the 10-volume Ragmud Collection, the Columbus artist tells the story of her family, from their enslavement through their migration north. The section on display celebrates the creation of “Black towns,” places where African-Americans could live and engage in commerce.

Given that quilting has so often been associated with women, it comes as no surprise that many of the works explicitly argue for women’s rights, including the iconic International Honor Quilt, initiated by Judy Chicago.

Two of these also show the intersection of pop culture and quilting.

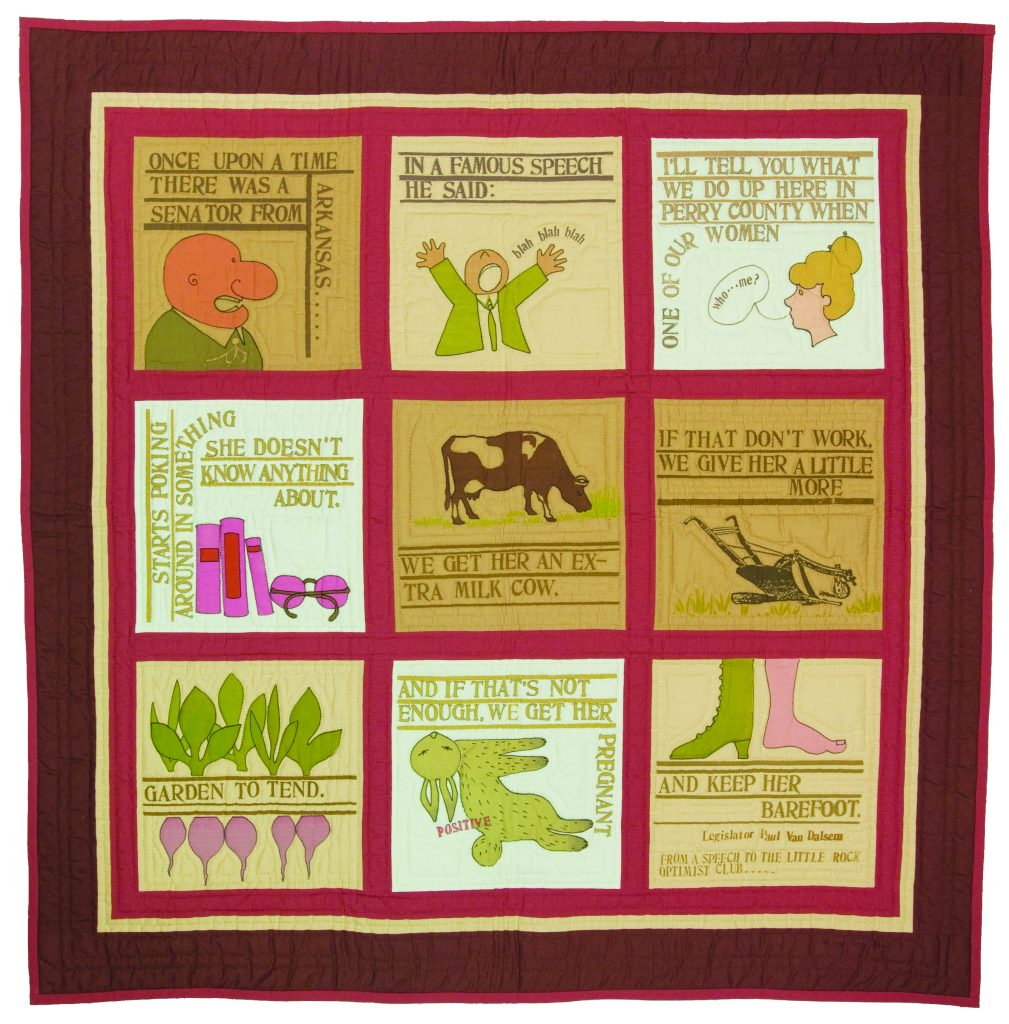

“Barefoot and Pregnant” by Jean Ray Laury uses panels with cartoon-like panels to ironically illustrate the statement from an Arkansas politician about what they do to a woman “who starts poking around in something she doesn’t know anything about.” The comic style makes fun of his speech using the politician’s own words.

LJ Roberts’ wild creation, a quilted van made from yarn, bike inner tubes, leather, metal studs and other materials celebrates the VanDykes, a lesbian and transgender collective that roamed the country in conversion vans.

The quilt, Applebaum says, has an almost apocalyptic vision as well a sense of the transient and the resilience of queer culture, and is laced with wordplay.

“Stand Your Ground” by Choctaw-Cherokee artist Jeffrey Gibson draws on traditional indigenous crafts, contemporary dance culture and headlines. “Stand Your Ground” applies both to the legal doctrine invoked in the killing of Trayvon Martin as well as to the Standing Rock Sioux protests over the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Nearby hangs a work from Ojibwe-Lakota artist Gina Adams “Broken Treaties Series.” Using parts of old quilts, she presents the text of treaties between indigenous peoples and the U.S. government. The text is layered and obscured, almost impossible to read. It expresses, Applebaum said, “the purposeful inscrutability of the treaties.”

Some quilts serve more conventional purposes, such as the Red Cross quilt, embroidered with the names of donors. The sale of the quilt aided the Red Cross efforts during World War I and the Spanish flu pandemic.

Sections of the AIDS quilt are also included. As with so many traditional quilts, the creators are anonymous, yet those who the quilt memorializes are not.

That’s not the case in a more recent example. The Migrant Quilt Project that memorializes those who have died trying to cross into the United States from Mexico.

The foreclosure crisis, the Holocaust, and the toll of climate change are all addressed in the exhibit.

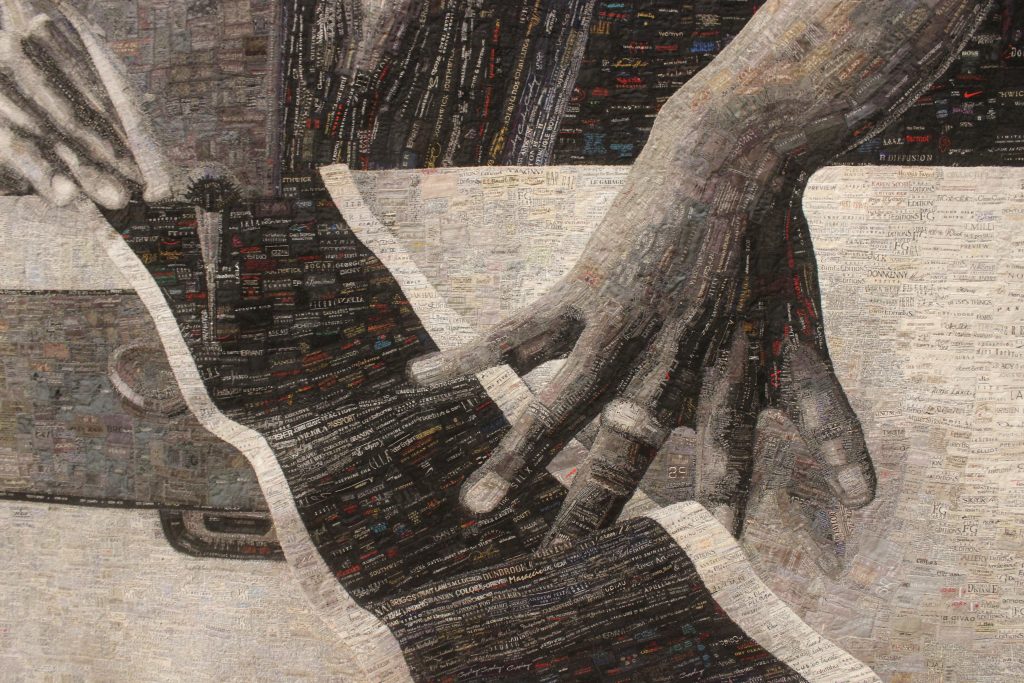

Therese Agnew’s larger than life-size “Textile Worker” encapsulates so much of what’s intriguing about the exhibit. Agnew recreates a photo of a sweatshop in Bangladesh where women sew garments for fashion houses around the world. She assembles the image with more than 30,000 clothing tags cut from shirts, pants and other items of clothes. If you look close enough you can read the company names on the face of the worker.

“The goal is to call out these fashion labels and show the unfair labor practices in the textile industry and recognize the textile workers,” Applebaum said.

There’s a sense of kinship that comes through, shared among those striving to create a better world one stitch at a time.