By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Writer Michael Martone introduced readers in Bowling Green to maybe his greatest character — Michael Martone.

He’s a writer whose flights of fancy have taken him to all corners of his native Indiana, a place he said where not much happens and no one visits, even Hoosiers. And when he takes a leap of imagination into the future, he doesn’t expect it to be any different.

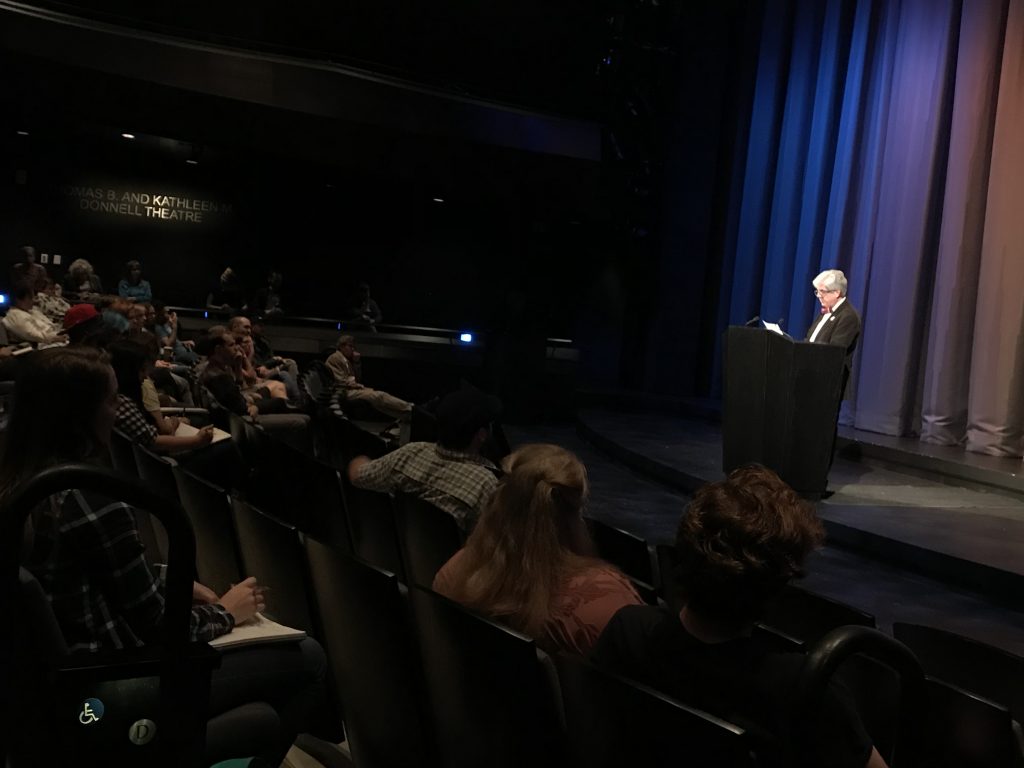

Martone, who now teaches in the writing program at the University of Alabama, read from and commented on his fiction with a wry humor that blurred the line between fact and fancy, something he works hard to achieve. His reading last week in the Donnell Theatre was billed as one of the university’s premiere arts events.

In his “Blue Guide to Indiana,” for which he received an injunction forcing him to acknowledge it really wasn’t part of the Blue Guide travel series, he wrote about a federal office that studied coffins in Batesville, Indiana, the headquarters of the coffin manufacturer.

Later he received a call from a Washington Post reporter who was writing a story about odd federal agencies. He inquired about the coffin study office. Martone allowed that he’d made it up. The reporter was disappointed. It was one of the more interesting ones.

Martone’s shelf of literary honors attest that the reporter is not alone in his assessment of the author’s fancy.

Martone opened with a short story from his self-titled book “Michael Martone.”

“I like books with names in the title,” he told the audience, then rattled off a short list “David Copperfield,” “Jane Eyre,” and “Huckleberry Finn,” before adding his own “Michael Martone.”

The book is made up of 150 contributor’s notes, those short biographical sketches included in the back of literary journals, all for Michael Martone.

He submitted these to magazines, which caused some confusion. A magazine would accept one, and then ask for an actual contributor’s note, and Martone would send another fictional one. “These are real contributor’s notes,” he would tell the exasperated editor.

Martone said he wanted the notes to be published in the back of the magazine with those of other contributors because that’s all people read anyway.

This particular note grew from a couple Wikipedia-verifiable facts. Martone was born and raised in Fort Wayne, and his mother was an English teacher. It goes on to recount a couple early literary successes only to note dryly that his mother actually wrote them, as she did all his other work right up through his graduate thesis. It was not at all clear if he wrote any of his work, including the contributor’s note he was reading.

Martone’s world includes Musee de Bob Ross, dedicated to the creator of so many “happy trees” in his art instruction program that still airs in repeats on “the PBS,” as Martone calls it.

His world includes Winesburg, Indiana — a sad place that was sued by the self-same named fictional Ohio town created by Sherwood Anderson.

The high school there is named for Emile Durkheim, the father of sociology whose first book was “Suicide” and all the middle schools are named for assassinated presidents.

In his world, a thermostat can be sexy — though not sexy enough for the story to get accepted by the online journal that solicited it.

It’s a world where an award-winning author gives out his cellphone number so members of the audience can text him during the reading. Martone lamented he was still flummoxed enough by his flip phone that he couldn’t respond immediately during the reading as certainly a young person could.

As he closed, he again solicited text messages. Because he was on “the double-wide tour of Ohio and Indiana,” he may not be able to respond right away. Or maybe it just takes his mother longer to write on a cellphone.