Ohio Capital Journal

Kevin Verhoff remembers the days when he needed public transportation the most.

Living in San Francisco, he rode the bus or took the BART rail system to work. Years later, in New Jersey, he dealt with frequent car troubles but thankfully had access to a nearby train line to get to work in Newark.

“It was very convenient for me,” he said of those experiences. “It made a big difference in my day-to-day life.”

When the Elyria native moved with his wife back to Ohio, the return was something of a culture shock. Ohio is the most-populous state in America without a state-supported passenger rail service, according to the transportation advocacy group All Aboard Ohio.

Verhoff now lives in a community about 40 miles outside of Columbus, which is said to bethe largest metropolitan area in the entire western hemisphere without passenger rail service. And the capital city’s population is only rising.

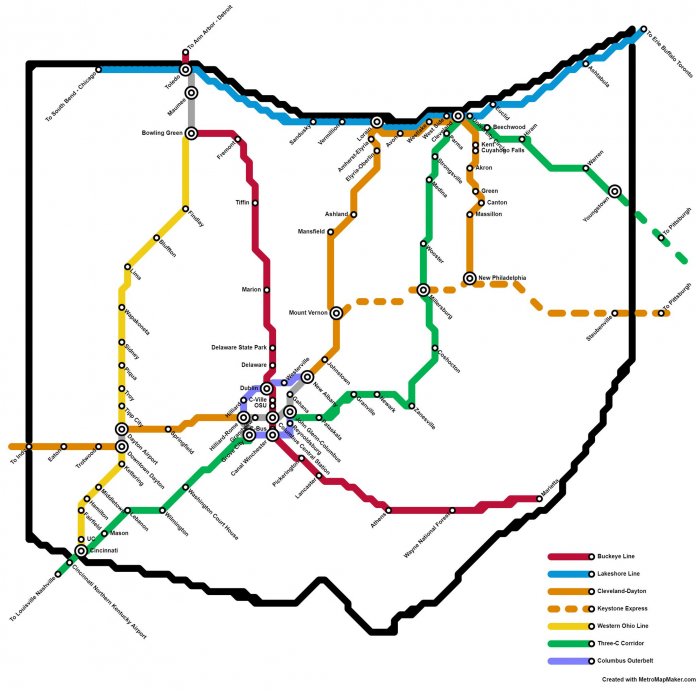

The self-described “data nerd” and transportation hobbyist decided to put his skills to good use. Verhoff recently developed his own proposal for a passenger rail system that would criss-cross the Buckeye State. In sum, his proposal features seven different rail lines with stops in half of Ohio’s 88 counties. This would be part of a broader vision of a rail network connecting the entire Midwest. Think of a rider in Mansfield taking the train north to Lorain, then hopping aboard the Lakeshore Line all the way to Chicago. Imagine a rider in Ashtabula taking a trip to Toronto, with a pit-stop in Erie, Penn.

Creating an intercity passenger rail network in Ohio, Verhoff admits, would be an immense undertaking. There are the obvious issues of funding and land right-of-ways, of course. Just as challenging are the intangible hurdles: How do you bring politicians, business leaders and other stakeholders together from the local, state, regional and federal levels to work toward this singular goal?

More existentially, how do you spur action today for a project that may not be completed until decades from now?

Verhoff is an avid bicyclist, which is to say he’s a patient optimist. Millions of lives would change if this project becomes a reality. The trouble is worth the effort, he maintains.

And so, back in Ohio again and back to relying on his car, he studies the map of Ohio and dreams.

‘’It’s crazy to think how close we were’

Verhoff’s map was not created from whole cloth.

In fact, he took much of the inspiration from previous attempts within Ohio government to build such a system.

The most recent effort came — and died — in 2010.

Transit supporters are still bitter about how it all fell apart.

After decades of studies and environmental work, officials concluded in the 2000s that a rail corridor between Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati was a worthy pursuit. The Federal Railroad Administration agreed, and eventually pledged $400 million toward building the “3C” line.

It was thought that federal funding would go a long way in financing the project. Negotiations were underway between public and private interests in order to utilize existing freight track. This would’ve saved enormous amounts of money in not having to build an entirely new rail infrastructure.

It’s unclear, looking back, how much more the state would have had to kick in to pay for the capital costs of creating the 3C line. The Ohio Rail Development Commission notes the state would’ve been responsible for an estimated $17 million annually in operating and maintenance costs. In 2019, that would have amounted to 0.4 percent of the Ohio Department of Transportation’s multibillion-dollar budget.

Stu Nicholson, the public affairs director with All Aboard Ohio, said the 3C plan was to build a “start-up service of six to eight trains a day, with the intent of following up with upgrades in both speed and frequency of service.”

However, 2010 was the year of the Tea Party, and curbing government spending was a major policy priority for Republican candidates throughout the country. John Kasich was the Republican challenger against incumbent Democrat Ted Strickland, and was explicit in his plans to kill the 3C project if elected governor. He kept his promise, and the federal government revoked the $400 million in order to spend it elsewhere.

There would be trains running today between Ohio’s most-populated cities, Nicholson said, if it weren’t for Kasich’s intervention.

“It’s crazy how close we were,” Verhoff said.

The Verhoff Plan

Verhoff drew from that 3C project and an earlier study known as “Ohio Hub” to create his own map. Many of his routes, plus the overall cost estimate, were inspired by these earlier attempts.

The map Verhoff created features seven different rail lines. The most familiar is the “Three-C Corridor,” which adds to the earlier 3C plan by including many stops along the way — in places like Medina, Wooster, Zanesville, Grove City and Lebanon.

There’s a “Western Ohio” line connecting Cincinnati with Toledo; a “Keystone Express” line connecting Knox County in Central Ohio eastward to Steubenville; a “Columbus Outerbelt” line resembling the shape of Route 270; a “Cleveland-Dayton” line running through the middle of Ohio; and a “Lakeshore Line” running parallel with the shore of Lake Erie.

One proposed line that has proven to be popular, Verhoff said, is the “Buckeye Line.” This would run from Toledo southeast-ward through Columbus and down into Appalachia, with stops in Lancaster, Athens and Marietta.

Verhoff points out that transportation is an issue which intersects with health care, economy, jobs and tourism. Someone living in Marion could easily travel to Columbus for regular treatments. A person in Canton could ride north for classes in Cleveland.

In the case of the Buckeye Line, an outdoors enthusiast could ride toward Athens and enjoy the Baileys Trail system, a massive bike trail project being built within the Wayne National Forest.

Verhoff posted the map to his blog and on Twitter. The positive responses surprised him.

“A lot of people were saying ‘this would totally change my life,’” he said.

It didn’t take long before others began asking, why doesn’t my community get a rail stop?These requests came from all over. Marysville. Circleville. North Ridgeville.

Verhoff is heartened by these comments. It proves, he believes, how the demand for public transit is widespread across Ohio.

The main thing, he told the Capital Journal, is balancing volume versus coverage. The more lines and places served, the better — but that can mean fewer trains passing through a place each day.

As to the matter of paying for all this, Verhoff estimates a $9 billion cost to build this statewide network. (This does not include the anticipated post-construction operational costs.)

That’s a daunting figure, but spread out over 20 years it amounts to $450,000,000 per year, or around 10 percent of ODOT’s annual budget.

Verhoff posted a follow-up to his initial proposal, outlining a variety of other ways this system could be funded — such as through municipal bonds or in shifting highway and gas tax funding toward these transit priorities.

Others have pointed out that ODOT spends hefty sums on car-friendly projects. The Portsmouth bypass in Scioto County, completed last year and serving a town of 20,000 residents, cost $634 million. The transportation budget approved by lawmakers earlier this year includes funds to study a proposed “Eastern Bypass” around the area of Cincinnati. The eventual cost to build such a bypass? It’s been estimated to be between $1-5 billion.

Much of the $9 billion project cost could be mitigated, Verhoff said, by using and upgrading the privately-owned tracks throughout Ohio.

Ohio has nearly 5,200 miles of rail lines, according to the Ohio Rail Development Commission, with the vast majority being owned by freight railroads.

Still, the necessary environmental work would likely have to start again from scratch. Then there’s the process of getting legislators and ODOT on board, which Verhoff said would require a fresh push from grassroots supporters from all over Ohio.

Rail and Hyperloop?

That push is not coming from the state level, at least for the time being. There is, however, work being done on a local and regional level.

The Ohio Rail Development Commission outlined a few such projects in its 2018 “State of Ohio Rail Plan.” One involves a proposal to build a passenger line between Chicago and Columbus, with rail stops along the way in Fort Wayne, Lima and elsewhere. A feasibility study was completed in 2013 and next is the lengthy environmental work.

A similar proposal from the Mid-Ohio Regional Planning Commission was announced just last year. MORPC is conducting its own study of a proposed rail line between Chicago, Columbus and Pittsburgh. The commission is also looking into the potential “hyperloop” between the cities. Hyperloop is the technology popularized by Tesla CEO Elon Musk in which riders travel in high-speed tubes.

The ORDC plan also details a number of Amtrak station improvement projects in the works in places like Cincinnati, Cleveland and Toledo.

Ken Prendergast, executive director of All Aboard Ohio, described these efforts as being “probably an achievable first step for Ohio in pursuing an incremental passenger rail development program.”

Prendergast said his organization is appreciative of Verhoff’s advocacy and hopes the attention drawn to transit issues will make an impact.

“(The) real work comes in educating Ohio’s policymakers how far ahead our neighboring states are in developing, improving and operating passenger rail services, and what benefits they are enjoying from those investments,” he noted.

It will take some convincing to get state officials back on board. The Ohio Department of Transportation has its own set of guiding principles called Access Ohio 2040, which details a number of “long-term transportation outcomes” ODOT hopes to achieve in the next two decades.

The plan does not mention a passenger rail system in Ohio. Instead, one stated goal is to “ensure, enhance and improve access to the existing multimodal system.”

Funding, land, politics, time — these are significant hurdles to building Verhoff’s dream.

In his mind, every year of inaction is one more year without improved public transit opportunities down the road. The need for this system, and the benefits it would bring, make the dream worth pursuing.

Verhoff is now working on an improved map draft, one that might include a few requested cities like Chillicothe and Portsmouth. It’s back to the drawing board.

Verhoff’s proposed lines:

Columbus Outerbelt

- Takes the shape more or less of Route 270. Would have stops at John Glenn International Airport, Westerville, Dublin, Hilliard, Hilliard-Rome, Grove City, Canal Winchester.

Three-C Corridor Line

- This is the longest route, and travels in sort of a diagonal path from Cincinnati through Columbus and up to Cleveland. From Cleveland it continues back southeast-ward to Youngstown. On either terminus, there are suggestions for the line to continue in other states. (The Cincinnati end could connect with the airport just over the state line in Hebron, Kentucky, while the Youngstown side could carry on toward Pittsburgh.)

- There are numerous stops along the way. In Southwest Ohio there are stops in Mason, Lebanon, Wilmington and Washington Court House. On the other end are stops in places like Zanesville, Coshocton, Wooster and Medina while heading up to Cleveland.

Western Ohio Line

- This connects Toledo with Cincinnati, with stops in places like Dayton, Lima, Findlay and Bowling Green.

Keystone Express

- This shorter line would be located in the eastern-central portion of Ohio. It would connect Mount Vernon in Knox County eastward to Millersburg, New Philadelphia and Steubenville. (There is a suggested continuing line toward Pittsburgh.)

Cleveland-Dayton Line

- This has a similar trajectory as the Three-C Corridor line, but takes a slightly different route in order to hit a number of different stops.

- Starting in Dayton, it travels through Springfield, then through Columbus, then northward to hit Mount Vernon, Mansfield, Elyria, Lorain and a few other towns along the lake. After reaching Cleveland, it heads due south to connect with Kent, Akron, Canton and Massillon with a terminus in New Philadelphia.

- (There is a suggested path westward from Dayton to hit Trotwood, Eaton and continue on toward Indianapolis.)

Lakeshore Line

- Cedar Point and Cleveland sports fans can rejoice with this proposed line. It runs the length of Ohio’s Lake Erie shore, beginning in Toledo and heading east through Sandusky, Vermillion, Lorain and then Cleveland. It continues on to include Euclid and Ashtabula. (A suggested continued path to Erie, Pennsylvania; Buffalo, New York; and possibly to Toronto.)

Buckeye Line

- This criss-crosses the state in a diagonal path opposite the Three-C line. It begins in Marietta and passes through Athens, Lancaster and Columbus. It continues northeast-ward to connect with Marion, Tiffin, Fremont, Bowling Green and Toledo. There is a suggested continued path into Michigan with Detroit and Ann Arbor.