By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Dinner is served.

And whether that dinner is served in grandma’s dining room, a fine dining restaurant or a fast food joint, many, many hands played a role in bringing that food from the farm to the table.

Many of those people are migrants.

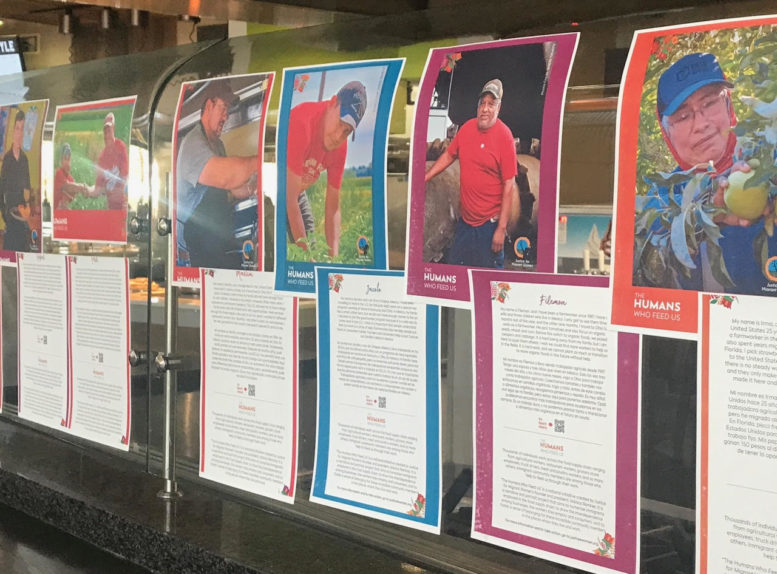

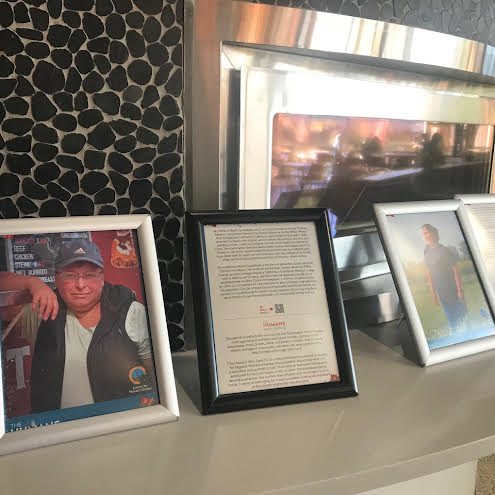

“The Humans Who Feed Us” project tells the stories of those workers.

“Often times we sit down for meals and we take it for granted that there are many individuals who played a part in bringing food to our tables,” said Mónica Ramirez. “I’m hopeful this project will help center the real human beings who do that work every day.”

Ramirez, the founder of Justice For Migrant Women, launched the project last summer at the Sandusky County Fair. The focus was local migrant farm workers. Each was featured in a photographic portrait and a short profile contributed by the worker. [See portraits and profiles]

The project has expanded for Thanksgiving, featuring more workers, who do a greater range of jobs, with the profiles shown in about 100 venues. Those include the Oaks Dining Center on the Bowling Green State University campus and Guajillo’s Cocina Mexicana in Bowling Green.

“This tool of using narratives is so important if really you want to achieve change for these workers, many of whom are migrants,” Ramirez said in a recent telephone interview. “My experience has been that when we’re able to share the story of real people and do what this project hopes to do, which is humanize them, then we start to see issues and problems in a different light. It means so much more to hear directly from an individual about what their hopes, dreams and needs are than to hear from me or a political leader,” she said.

“This project is personal. It’s about people. It’s about helping community members to know the people who feed them and think about the people who feed them.”

Many of those workers, Ramirez continued, still lack the basic protections other workers have. She wants the “Humans Who Feed Us” to do more than “change hearts” but also help bring reforms that give those workers basic rights.

Vibha Bhalla, a professor in ethnic studies, was instrumental in bringing “The Humans Who Feed Us” to campus. She had worked with Ramirez earlier in the semester on a Day of the Dead display.

Bhalla, who is one of the organizers of the Immigrant Ohio Conference, said when she first started teaching about migration at BGSU, she knew little about what was happening in Ohio. In order to make the course more relevant to her students, she started to delve, and have them delve, into the immigrants around them and in their own families.

Many students come from rural Ohio and some come from families of migrant workers.

Chad Carper, the general manager of the Oaks, grew up in the Tiffin area. He remembers as a kid going to the drive-in movies. It was one price per vehicle.

He recalls seeing the workers from the nearby Riehm Farm come in packed into trucks, complete with couches. As a kid he was impressed. Later, he learned more about who they were. “It was their night on the town,” he said.

He was pleased to work with Bhalla hosting the exhibit. “It really goes to what BGSU is about, which is shining a light on social issues. I think it’s cool.”

He said he found himself falling behind setting up the portraits because he wanted to read them all. The exhibit features “a lot of good stories about people,” Carper said. “It’s shedding light on these people. They’re not here being criminals. They’re just here trying to carve out a life for their families and just working hard and chasing that American dream just like everybody else. They’re doing jobs nobody else wants.”

It’s unfortunate in the current political climate that they’ve been “vilified” and accused of “taking our jobs.”

Bhalla said it is not just recent but goes back 80 years to the founding of the Bracero Program that brought Mexicans into the United States to pick crops. The program eventually ended but not the need for workers.

“Food in America is so cheap because we underpay these workers,” she said. They also often get no benefits.

“They’re people,” Carper said. “They’re working hard, so we can put food on our tables to feed our families so they can make money and do the same for their families.”

Among those featured in the Oaks is Jacobo from Chiapas, Mexico. For the past five years he’s traveled to Ohio on a special visa program to work for the Riehm family.

“I think it is important that people understand that our work and our relationship is a circle of help. We help people put food on their tables through our work. Farmers and consumers help us put food on our families’ tables in Mexico through our jobs,” he says in his profile.

Rufina works for Hirzel. Her family has been in Fremont for the past 10 years. The stability at Hirzel is “very good.” Before that her family migrated from state to state.

“Even with the advancements of machines in farming, farmers always need farmworkers,” she says in her profile. “They depend on us to pick the best produce. The issue with the work is that it is hard, and we are working under the sun all day.”

Ramirez grew up in the Fremont area. Her parents did agricultural work early in their lives. But a farmer in Mississippi helped her father learn to read and write, so he could continue his schooling. When he moved to Ohio, he got a factory job.

But he made sure his children still knew about their roots.

So when Mónica was 14, she was struck when the local newspaper published a special insert welcoming fishermen back to the area. She wondered why they did this for anglers when they didn’t do anything for farmworkers who arrived at the same time.

She asked her father about it. He didn’t know, but encouraged her to inquire. So she pedaled her bike to the newspaper office and spoke to the editor.

She knew his children. He was very courteous and said maybe she could contribute stories about farm workers and the local Latino community.

That was the beginning of her activism, Ramirez said. “I didn’t know that was called activism.” She was just “trying to help the community better understand the Latinos in the community.”

That’s the foundation of her work some three decades later.

Now an attorney, she considers herself an organizer. She started doing outreach informing people about their rights. While there has been incremental change there’s not been significant changes, Ramirez said.

She founded Justice For Migrant Women. “The majority of my career has been representing farm workers and other immigrant women workers specifically in sexual harassment and gender discrimination that many of these women experience,” she said.

Included in the exhibit is a photo of Jacobo with Phil Riehm, the fifth generation of Riehm farmers. Riehm writes: “Consumers need to understand that there are many people who help to grow the food that we eat. It’s important to support local farmers and farmworkers. Food that is produced on these small farms and purchased directly from the farmer provides the best flavor and nutrition. A lot of the workers who do this work are immigrants, like the workers who we employ who travel to the U.S. to work on visas.

“These workers are good people who do good work. Many migrant workers sacrifice to leave their homes and their families to do this work, whether they come on visas or travel from within the U.S. I am grateful to them, and I know that they are thankful to have a good job. We have nothing but mutual respect for one another.”