By JULIE CARLE

BG Independent News

Memories about the Vietnam War have been part of history for more than 50 years. Over time, those memories have evolved but not disappeared.

“The Vietnam War is still with us because there is a living memory,” Dr. Bill Allison said during the recent Gary R. Hess Lecture hosted by the Bowling Green State University Department of History.

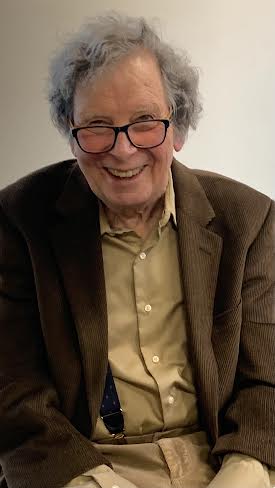

Allison, who received a Ph.D. in history from BGSU in 1995, was one of Hess’s graduate students. He is a professor of history at Georgia Southern University, specializing in military history, and an author of numerous books. He also hosts with Brian Feltman the “Military Historians Are People, Too” podcast.

His presentation, “Contested Memories: The Vietnam War Fifty Years On,” was based on one of his latest areas of scholarly research: how narratives about the Vietnam War and other conflicts are created and how they change over time.

“It doesn’t matter if you are a hawk or a dove, right or left, if you served or didn’t; the war is something that was there. Vietnam was a traumatic time in your life no matter how old or young you were during those years,” he said.

The public’s perception of the war has changed over time. Right after the war, Vietnam veterans were often considered “damaged” and portrayed in television shows as the bad guys. That view started to change in late 1980 when “Magnum P.I.” first aired. The series was one of the first to depict Vietnam vets as well-adjusted, productive members of society.

After the Vietnam War Memorial was installed in 1982 and the first Gulf War began in 1990, perspectives evolved again.

“Our collective guilt about Vietnam and the way we treated the people that served in the war moved toward honoring Vietnam veterans. They have a comeback, a resurgence,” Allison said.

“At one point, there may have been a time when you lied about serving in Vietnam, and in the ’90s you might have lied to say you were in Vietnam. It’s stolen valor.”

A false sense of masculinity that a veteran of war only truly served if they were in combat contributed to problem, he said. Yet, for every one person in the field, there are five or more people who are doing other jobs supporting the cause.

“We have to remember that most people who serve in wars don’t carry a gun; they don’t see war up close. They are driving trucks, pushing paper, serving as medical personnel, running the big super bases at Cam Rahn Bay, at Long Bihn or Da Nang,” he said.

The discord between the masculinity standard and what constitutes service caused the conflict about how to honor the Vietnam veterans. With 50-year retrospectives of the war currently in play, Allison said, “I think we are entering a phase of more respectful forgetting. We are slowly starting to forget the war because the older generation from the ’60s who served are fading out.”

There are still people like Allison, “who lived with it because my dad was in it,” but there are a lot of people who are more recently born who have little to no recognition of Vietnam.

Vietnam memorial mania erupts

With changing attitudes about the Vietnam War, interests in building memorials has increased

exponentially.

“Their design, who builds them, who funds them, where they are placed and what they are used for is an amazing study in our human psychology and how we deal with different memories and traumatic experiences,” he said.

The national Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, D.C., started the evolution in the United States, despite a somewhat tumultuous start. Vietnam veteran Jan Scruggs had the idea to build a Vietnam memorial in the nation’s capital. There was little interest until TV reporter Roger Mudd interviewed him on “60 Minutes.”

“Suddenly the gates opened and he had $8 million dollars in a matter of months to support building the memorial,” Allison said. A design competition was announced and 1,400 design concepts were submitted. The criteria included that the design had to list the names of the fallen soldiers and it could not be a political statement.

Maya Lin, a young architecture student at Yale won the blind competition. “Once her name was released to the public, all hell broke loose. A lot of veterans’ groups protested because they didn’t want their war memorial designed by someone of Asian descent,” he said.

Once the memorial was built, attitudes changed. Lin’s design, which was influenced by Edwin Lutyens’ war memorials such as the Cenotaph in London and the Thiepval Memorial in France, has become the most-visited monument on the National Mall.

Visitors were respectful and considered the memorial as if it was a cemetery, “like those 58,000 names were actually interred in that space,” Allison said. People are hushed and solemn when they visit the national monument or the traveling versions.

Once this reverence for Vietnam veterans was realized, veterans across the country decided to spearhead memorials in their hometowns.

“What do they all have in common? They look like Maya Lin’s memorial, maybe because it’s such a great design it can’t be improved upon, or they want it to be instantly recognizable because everyone knows that the national monument looks like and knows what it is. It is kind of brilliant, actually,” he said.

The phenomenon started in the 1980s after the national memorial was built and continues today. There are nearly 500 Vietnam-specific memorials across the country, but other veterans’ memorials are also being built.

Many communities are dedicated to commemorating their veterans and their service. Bowling Green is a community that has installed new memorials, one at the Wood County Courthouse and one just west of the BGSU Jerome Library.

The memorials are for the veterans. Especially while they are around, they have a place for commemoration, he said.

Retrospective on Ken Burns’ ‘The Vietnam War’

American filmmaker Ken Burns took on telling the story about the Vietnam War through his 18-hour documentary “The Vietnam War,” which debuted in 2017. Allison praised Burns for theextraordinary effort—10 years, at least 80 interviews, $30 million, and a reputable team of consultants and historians.

“Burns does a lot of good work, but he has to get in a truth that he wants to try to get at. He has to tell a good story, keep the audience engaged, and he has to entertain. “But taking on Vietnam was just fraught with peril,” Allison said.

Burns chose to focus on combat and frequently used the memories of Marine veteran John Musgrave, “who has a very compelling, very tragic, very fascinating personal story that he shares throughout the series. As compelling as the story is, we need to remember you can’t paint a broad brush that all Vietnam veterans are like John Musgrave, that they are damaged.

“Musgrave has been a wonderful voice. He’s a poet, a story teller and he has done great good with that role, but the left didn’t like that (the documentary) left out too many voices and the right didn’t like how (President Richard) Nixon was portrayed,” Allison said.

Because the war was so long, everyone has a different, individual experience that is based on when and where they were in Vietnam.

He contrasted the voice of Vietnam veteran James Willbanks, who was an Army officer who volunteered to go to Vietnam in 1970 and who also was wounded. “His experience was 45-degree angles off of the M-16 (rifle), but he is not a fan of the ‘damaged veteran.’ One of Jim’s constant messages is ‘You’ve got to remember, the other guy gets a vote,’” referring to the veterans who did not see active combat but were still impacted by the Vietnam war.

Allison believes the Burns’ documentary “suffers from too much time.” Because of changing memories, if the Burns documentary is produced 50 years from now, the Vietnam veterans will not be around to defend a memory or promote their stories.

“Memories of war are changing. Veterans are getting older and their memories fade. It’s a part and parcel of life,” Allison said.

“It is really a great time to be a historian-scholar,” Allison said. ”This idea of memory and how it’s so fluid changes the range of subjects it touches.” Historians will continue to study the operational history of the war, but younger scholars are contributing to the discussion on topicssuch as musicology, cultural studies, women in the military.

The Vietnam War wasn’t the only memory contested during Allison’s talk. Hess relayed a story of Allison’s early days as a doctoral history student. He recalled the first paper he turned in as being “damn good.” Allison’s memory of the paper was different. “I remember you writing in the margin, ‘Your writing style is turgid.’ I didn’t know what that meant but it didn’t sound ‘damn good’ to me.”

[RELATED: Vietnam vet dogged for half a century by memories of his year at war]