BY: TYLER BUCHANAN

Ohio Capital Journal

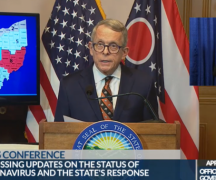

Dr. Bruce Vanderhoff acknowledges that as the public face of the Ohio Department of Health he is repeating himself a lot these days.

But the message is important enough to continue repeating in simple terms, ODH’s chief medical officer said Wednesday.

“It really comes down to, are you vaccinated and safe or are you unvaccinated and vulnerable?”

Ohio once again finds itself at a crossroads. After months of declining rates of new cases, hospitalizations and deaths, Ohio is now seeing increases thanks mostly to a new “Delta variant” that officials say is even more contagious.

I think it is absolutely the case that we are now looking at a pandemic of the unvaccinated.

– Dr. Bruce Vanderhoff, Ohio Department of Health

Vaccination rates here have all but stalled, concerning those like Vanderhoff who fear the state will slip back into a public health crisis as schools look to return to class next month.

“I think it is absolutely the case that we are now looking at a pandemic of the unvaccinated,” he told reporters .

Vanderhoff was joined by two pediatricians, including Dr. Patty Manning-Courtney, the chief of staff at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. The recent rise in cases has them worried not just of the Delta variant, but what else could be on the horizon.

Manning-Courtney said her hope is Ohioans will get vaccinated before the state experiences an even worse variant that could significantly impact the youth population. She fears a scenario of Ohio learning “the hard way” that vaccines are necessary for public health.

The latest surge

The state’s COVID-19 numbers declined throughout the spring, leading Gov. Mike DeWine and ODH to rescind the swath of public health mandates.

There was reason for optimism: The two-week average was down to just 17.6 cases per 100,000 residents as of July 7.

But since then, that average has more than doubled to 37.8.

On Tuesday, the state reported 744 new positive cases within the previous 24 hours, a daily total that hadn’t been seen since May. The state is recording a greater proportion of cases and hospitalizations among younger people, according to ODH data.

“It appears that this surge is being driven by yet another variant, the Delta variant,” Vanderhoff said, “which is, as I’ve shared before, even more contagious than the (alpha) variant that preceded it.”

The Delta variant is now present in more than one-third of all new cases in Ohio and is on its way to being the dominant variant of COVID-19, Vanderhoff said.

‘Captains of the ship of their own health’

Unlike a year ago, when mitigation tactics like distancing and face masks were seen as the most effective ways to protect oneself from the virus, a proven vaccine is now available for Ohioans.

But it remains difficult to convince a majority of residents here to get vaccinated.

A vast number of Ohioans received shots when they were first made available, with a boost in vaccinations this spring with the widening of eligibility and the announcement of a Vax-A-Million sweepstakes. (Franklin County is among the places still experimenting with vaccine incentives; those who get their first dose at Columbus-area clinics receive a $100 Visa gift card.)

On the whole, the statewide vaccination rate has stagnated. More than 5.3 million Ohioans have completed their vaccination doses, but that still reflects just 45.5% of the total population.

DeWine had said his lottery idea was meant to target those who were not anti-vaccine, but needed some kind of boost to schedule their appointment.

Now, after months of availability, Vanderhoff and others believe there is still a large segment of the population who can be convinced. These are well-intentioned people with understandable concerns that can eventually be swayed to change their minds, the officials hope.

Misinformation spread online and in public spaces isn’t helping matters. Vanderhoff agreed with a recent statement by President Joe Biden that vaccine misinformation shared around on social media platforms is contributing to ongoing hesitancy and COVID-19 deaths.

“I think there have been people who are sharing information in a very authoritative way that is not scientifically accurate,” Vanderhoff said. “As a physician, that’s very distressing, because we want people to make their own decisions of course. We want people to be the captains of the ship of their own health, but we want them to make their decisions on the basis of good, well-founded, scientific information.

“Frankly, it’s heartbreaking when we see people who are cascading information that is not scientifically based,” he added.

Dr. Amy Edwards, the associate medical director of pediatric infection control at UH Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital, said vaccine misinformation has been around long before the coronavirus. She noted an example of seeing a child die of the whooping cough.

“That’s unacceptable to me,” she said. “It should just never happen.”

Vanderhoff and the pediatricians tried to dispel fears about the vaccine harming children. They noted rare cases of myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart muscle that has been reported in a small number of children this year.

But Edwards called this a “rare side effect” that impacts as few as one in every 100,000 or more that receive the vaccine.

“The risk is much higher from the virus itself,” she said.

While there continue to be some examples of vaccinated people getting COVID-19, most are protected against serious outcomes like hospitalizations and deaths.

All of the 130 people in Maryland who died of the virus in June were unvaccinated. Other states have reported similar statistics, including Alabama, where 96% of the COVID-19 deaths between April and mid-July were unvaccinated.

“The issue of breakthrough with this kind of a vaccine against this kind of virus,” Vanderhoff said, “is really the issue of: Are you seeing people get severely ill? Are they ending up in the hospital? Are they dying? We’re just not seeing that in appreciable numbers with this vaccine.”

Asked about future health orders with school returning in the fall, Vanderhoff said he could not disclose ongoing policy discussions within the state health department. He said ODH will be providing guidance and recommendations “in the near future.”