By JAN LARSON McLAUGHLIN

BG Independent News

When a World War II bomber fell from the sky taking a Bowling Green boy down with it, his devastated family sealed away their memories and never again spoke of their painful loss.

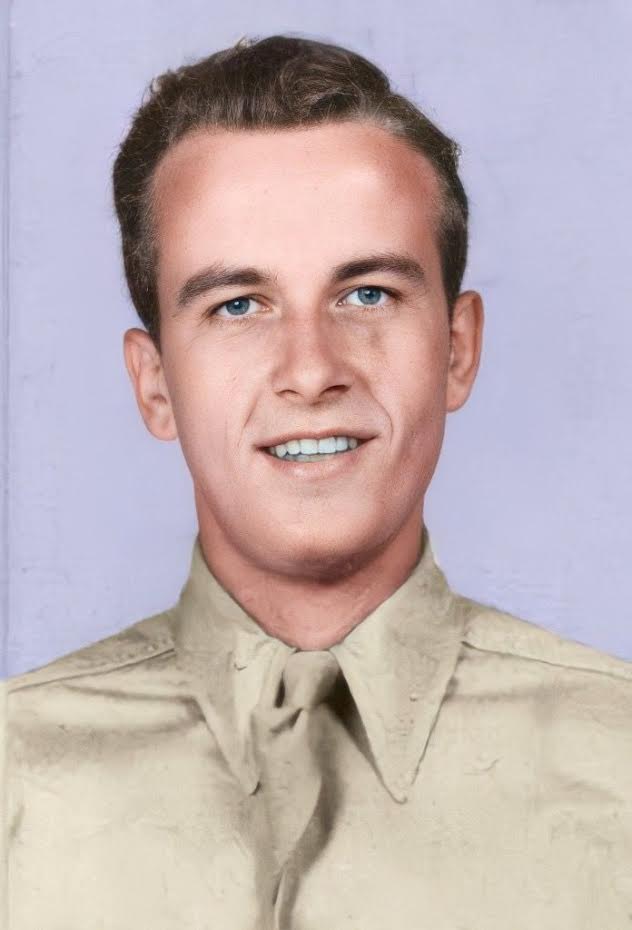

More than 70 years later, those memories were unearthed in a foot locker that held a treasure of 335 letters written home from the war. Those letters, transcribed from their rushed cursive writing, have now been turned into a two-volume book called “I’m in the Army Now: World War 2 letters of Glenn Max Whitacre.”

Whitacre, who grew up on South Summit Street in Bowling Green, served in the Army Air Corps during World War II, aboard a B-24 Bomber as a radio operator/mechanic and a gunner. He served from February 1943 until he was killed in a mid-air collision in July 1944.

Marty Whitacre, his nephew, knew little about him. The subject was too painful to be discussed by Glenn’s parents or brother Dale, who was Marty’s dad.

Then in 2016, Marty was rummaging through his mother’s garage for information to build a family tree when he happened upon a foot locker holding handwritten letters his uncle sent home to his family in Bowling Green. Inside were 335 letters, preserved for more than seven decades. The letters tell of the 19-year-old’s love for his family, his hometown, his sweetheart, and a longing for tall glasses of cold milk.

Glenn had been referred to as a “block wall” in the world of genealogical searches. Beyond his birth, death, family relationships and military service, nothing was recorded or passed down by the family.

“Beyond that I knew nothing. He was just another leaf on the family tree. Any further information was taken to the grave by my grandparents and father,” said Marty, who lives in California.

“Here in my hands was the information ‘not to be discussed,’” Marty recalled.

“Discovering the letters was only the beginning of this journey. As I look back on it now, it was truly the definition of locating family gems, just lying there in an old foot locker waiting to be discovered.”

“Typically, when a person passes away all you’re left with are some pictures and personal memories of that person. Predictably, this is where someone’s story ends,” Marty said.

“Even though the memories were too painful for my grandparents to share, they made sure to safeguard what he left behind. Perhaps in hopes that someday someone would help him tell his story.”

“It was quite a find. It was honestly emotional,” Marty said. “Now he gets a chance to speak.”

The almost daily letters were penned to his parents, brother and his sweetheart, Ruthie Cross. If Glenn missed one day of writing, he would sometimes write two letters the following day.

“He’s doing a lot of growing up away from home,” Marty said.

The letters tell of a young man wanting to serve his country, while homesick for his folks and younger brother, and desperately in love.

“He’s love struck beyond belief,” Marty said. At one point he returns home on furlough with a ring, and proposes to Ruthie.

Rationing paper, and often running low on ink, Glenn wrote on both sides of his paper. So in addition to his hurried cursive writing being a challenge to read, some pages bled over onto the opposite side, making it even more difficult to decipher.

It took his nephew about 18 months to transcribe the letters.

Initially, Marty planned to put the letters into a book form for about 20 family members.

But the project turned into a labor of love that Marty wanted to share with others. “I’m in the Army Now: World War 2 letters of Glenn Max Whitacre” can be purchased on Amazon. A blog can be found at https://www.iminthearmynow.com/

Volume 1 includes Glenn’s letters from induction, through basic training, radio operator/mechanic school, and gunnery school, at which time he’s granted his much anticipated furlough home.

Volume 2 includes all remaining letters during flight and combat training, as well as his travels overseas, combat missions, and an unfortunate sudden end to the correspondence when he was declared missing in action on July 29, 1944.

“I’m hoping they get a sense of what it’s like for one young man to commit to going to war to support this country,” Marty said.

Glenn’s first letter home was written on Feb. 6, 1943, and begins as many do with “Dear Folks…” He goes on to tell about the first meal in the military being “lousy.” It consisted of stew, sauerkraut, spinach and “some salad that made the guys gag.”

Whitacre tells his mom to “keep your chin up.”

He tries to keep the correspondence light. “I’m gonna practice playing 500 rummy and beat you all when I get home,” he wrote.

His language reflects the times, talking about his “swell” folks, “swell” scenery and “swell” meals.

Glenn talks about his favorite places back home in Bowling Green – the corner newsstand, Macs – a hangout for young people, and his dad’s business called Rudy’s Meat Packing.

“He was all about Bowling Green,” Marty said of his uncle.

Glenn talks about the rigors of training and war. He writes of an epidemic of measles going through his camp, and of being exposed to poisonous gas as part of their training. And he talks about the homesick soldiers, desperate for news from home.

“When mail call is sounded everyone runs like hell.”

As he prepared for furlough in November of 1943, Glenn’s letters reflected his excitement at coming home. “P.S. I’m all packed!!!”

When Glenn returned to the war in December, his letters had a different tone. He writes of his train rolling out of the station and watching his family disappear into the distance.

He talks of being homesick.

“For God’s sake, keep writing or I’ll go nuts,” he said.

On Christmas day in 1943, Glenn scribbles out a letter to his folks before heading to the mess hall.

“It’s a good thing I have 10,000,000 guys in the same fix as I’m in or I’d be more bitter than I am now,” he said, adding that it snowed where he was stationed in Italy. “So I at least got my wish for a white Christmas.”

After the meal, Glenn added more details. He told of eating a 10-inch long drumstick, potatoes and gravy, corn, dressing, ice cream and mince pie. “If they had only had milk!” he added. “I made a hog of myself – as usual.”

And he wrote of his hopes that the Christmas presents he sent home got there in time.

“I’d have given anything to have been home to watch you open your packages.”

On June 17, 1944, Glenn wrote of an unforgettable flight earlier in the day.

“I’ve always had faith in God, but after that mission, I have more in Him than ever before,” he said, promising to share more details with his folks when he got home.

“I don’t feel the least ashamed when I say that I was scared stiff, and that my kidneys gave way.”

Glenn’s last letter home was written on July 7, 1944. He talks about his 5 cent shave and 10 cent haircut. And he apologizes for his worsening handwriting – wondering how the military censors can even read his chicken scratches.

As in many of his letters, Glenn talks about how much he misses big glasses of milk that were always available back home. “Sure could go for some nice cold milk,” he wrote. And he talks again about his sweetheart back home, Ruthie.

“Boy, what I wouldn’t give to take a nice dip in the Lime Kiln (quarry) and then snooze on the rocks for a few hours. And better have Ruthie with me!”

Then the letters stopped. And the memories of Glenn’s service were locked away to be discovered by another generation.

Marty is looking for a home for other items packed away in the footlocker, like Glenn’s uniform – possibly the Wood County Museum. Eventually, he plans to donate the letters to the Center for American War Letters.

He is hoping others will become aware of the millions of these types of letters that are still packed away – or being thrown out without their value being realized.

And copying the phrasing often used by his Uncle Glenn, Marty signs off on his blog with “Be Swell, Marty Whitacre.”