By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

Master drummer Bernard Woma has greeted presidents and royalty to his native Ghana. On Tuesday morning he greeted students in Bowling Green State University’s School of Art with the throbbing sound of drums, and the swirl of dancers.

Most of those in the audience in the lobby of the Bryan Gallery were students in Rebecca Skinner Green’s African art class, but the ranks of listeners swelled as the rhythm reverberated around the building.

Most of those in the audience in the lobby of the Bryan Gallery were students in Rebecca Skinner Green’s African art class, but the ranks of listeners swelled as the rhythm reverberated around the building.

They didn’t stay observers for long. On the second dance, members of Woma’s Saakumu dance troupe summoned those in the audience to join the line, instructing them as they danced, on the steps and gestures.

“We share the music together,” Woma said. “We share the experience together, so you better understand.” Ghanaian music is participatory.

Woma has been coming to BGSU every few years since 2001. This week’s two-day stay with his dance troupe will culminate with a free performance Wednesday night at 7 in the Eva Marie Saint Theatre in Wolfe Center for the Arts.

He said that when he first opened his Dagara Music Center in 1998, a BGSU group led by Skinner Green and Steven Cornelius was the first to come to study there.

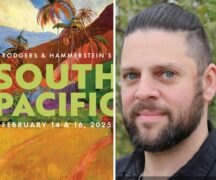

Bernard Woma demonstrates talking drum.

Woma said he was born to be a drummer. He came out of his mother’s womb with his fists clenched as if gripping a pair of mallets. That marked him as a gyil player. His grandfather played the instrument, a Ghanaian xylophone, as did his uncle. While his father didn’t play he loved to dance. So Woma grew up in a home full of music and dance. At 2 he was banging out the melodies he’d heard. His musical education began long before his formal “European” education. When he completed that, he headed to the capital city of Accra where he joined the National Dance Ensemble. The government brought together the best musicians from the country’s more than 60 ethnic regions. By the time President and Mrs. Clinton came to visit in 1998, he was the master drummer of the troupe.

Clinton was intrigued by the enormous ceremonial drum, and quizzed Woma on what it was made from. Elephant hide, Woma replied.

Saakumu percussionists

He also greeted the Obamas when they visited Ghana in 2009. He recalled that he was planning to come to the United States at that time, but the embassy said he needed to stay for the Obama visit. He even taught Sasha and Malia how to play the gyil. “It was privilege.”

As master drummer he also welcomed South African President Nelson Mandela and Queen Elizabeth.

With the founding of his school, Woma decided he needed to pursue graduate education. So he earned a master’s degree in African Studies from SUNY Fredonia and a master’s in ethnomusicology from the Indiana University. “It helped me understand the academic function of research to help students who want to study with me,” he said. “If I wanted to be a teacher, I had to learn myself about teaching and research.”

Seven students have completed master’s theses and eight have completed doctoral dissertations based on their work at his academy.

He now splits his time between Accra and Bloomington, Indiana.

Back home, people still value the traditional music and dance. Because the troupe knows the styles of all the various ethnic groups, they can play for people who have moved to the city, but still long from the sounds of home.

Woma shared insights into those traditions with the BGSU students.

He said the gyil was made of tropical rosewood, dried gourds, and spider webs. “We send children out to gather them,” he said. “Sometimes they get stung by a scorpion. It’s OK. It’s part of growing up.”

The design on the drums also has significance. One has the symbol of the Ashanti queen mother. She names the next king. Another is interwoven design symbolizes community.

These drums also served as models for New World percussion, the conga drum and the snare on a drum set.

That buzzing sound – that’s created by the spider webs on the gyil – is important. It adds a sense of electric energy to the music.

BGSU students and faculty join Ghanaian dancers.

The dances serve many functions. One mocked their countrymen who went to England to study and came back pretending they were white, wearing neckties, even when it was 100 degrees.

As the class time neared its end, it was time for students to learn another dance. This was a celebratory dance for young people.

Americans are used to multitasking, Woma said– drinking coffee, and driving at the same time. So, he said, they should be able to do the dance that called for them to clap, gesture, sing, and dance.

“Don’t make a mistake,” he said. “In Africa, every mistake is a new style, and we don’t need too many new styles.”