By DAVID DUPONT

BG Independent News

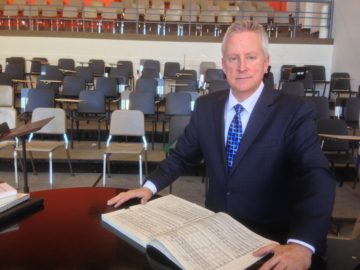

Mark Munson has been waiting for the academic and liturgical calendars to align.

The director of choral studies at Bowling Green State University wanted a year when Good Friday fell late enough in the semester to allow time to prepare and present J.S. Bach’s St. John Passion on Good Friday.

This is the year, and this past week the singers and musicians started the final phase of preparation.

Baritone Lance Ashmore

The passion oratorio, originally presented on Good Friday, 1724, is a large undertaking that involves soloists, the University Choral Ensemble, and the Early Music Ensemble, directed by Arne Spohr.

To help this large contingent of students, faculty and community members prepare, a leading scholar and tenor Christopher Cock, of the Bach Institute at Valparaiso University in Indiana, visited campus.

In the passion, Bach relates the story of Jesus’ trial and execution using the text from the Gospel of John, with reflections by soloists and the choir.

Cock has sung the role of the evangelist in the St. John Passion 50 times as well as conducted it on several other occasions. His choir has been in residence at St. Thomas in Leipzig where the piece was first presented, a rare honor for an American choir. He was at BGSU as the Helen McMaster Endowed Professor in Vocal and Choral Studies.

For many of the students involved this will their first time playing it. “I’m getting chills just thinking about you’re experiencing this work for the first time,” he told them.

Cock spoke about how Bach brought the theology to life in the music. “The debasement of being nailed to the cross,” he said, “was the only way Jesus could realize his full divinity.”

That comes through in the instrumental introduction.

The winds play a series of notes that overlap to create a dissonance “like a nail piercing a skin.” Cock said. The strings are restless, rustling, unsettled. The lower strings relentlessly lead the way to the choir’s entrance.

This music may indeed have gotten Bach into trouble, Cock noted both at the rehearsal and at a talk the next day.

Christopher Cock

Bach wrote the Passion in 1724, the first year of his employment at St. Thomas. He presented it again the next year, the scholar said, an unusual move.

This time that distinctive opening had given way to a more soothing introduction.

Cock said no one knows why, but he speculated that church authorities were bothered by that dark music. “The congregation had to be shocked and may have been disturbed” by the music.

Bach continued to refine and present the St. John Passion through the remainder of his life. He last presenting it in 1749. That opening passage was returned to its place.

The only instance Cock can imagine performing the piece without those measures would be on the 300th anniversary of the 1725 performance. “You miss that powerful opening.”

“The cantatas were composed for the liturgical days,” he said. And while the St. John Passion and the more celebrated St. Matthew Passion now are performed in concert halls at other times of the year, it still remains rooted in the liturgy.

That’s why in Bowling Green Munson has arranged for it to be performed Good Friday, April 14, at 7 p.m., in the First United Methodist Church. The Passion will serve as the community Good Friday observance, he said.

The Passion will also be presented on Palm Sunday, April 9, 4 p.m. in Hope Lutheran, 2201 Secor Road, Toledo.

Munson is using the 1749 edition of the piece, the last one that Bach actually had a hand in performing. By that time, Cock said, the composer had “returned everything back to where it was in 1724.”

Often, he said, the original “is the most powerful, the most direct” expression of an artistic impulse.

Though relating the Passion story as told in the Gospel of John, Bach took the liberty of interpolating two incidents from the Gospel of Matthew. Both are dramatic — Peter’s denial of Jesus and the tearing of the curtain in the temple.

Though relating the Passion story as told in the Gospel of John, Bach took the liberty of interpolating two incidents from the Gospel of Matthew. Both are dramatic — Peter’s denial of Jesus and the tearing of the curtain in the temple.

Cock said that Bach’s listeners would immediately have recognized these are coming from a different gospel – they knew their scripture far more than contemporary worshippers.

A more contemporary controversy looms over the piece.

Some of the language, particularly the passages dealing with Pilate’s asking the crowd how he should deal with Jesus have been criticized as anti-Semitic, laying the blame for Jesus’ death at the feet of the Jewish people.

The cries are chilling in light of all the history since, he said.

But one should consider the time when the gospel itself was written, he said, when there was a split between Jews who believed in Jesus as the Messiah and those who didn’t.

Citing Michael Marissen’s “Lutheranism, Anti-Judaism, and Bach’s St. John Passion,” Cock stated that the composer could have used more inflammatory language (as Handel had) and that the tone is one of relative moderation.

Cock said the controversy seems to have eased. It used to be, he said, that “as soon as I got off the plane” he was asked about the anti-Semitic claim.

(A three-page essay by Marrisen on the issue can be read at: http://ism.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/BachG%C3%87%C3%96s%20St(1).pdf.)

In the Bowling Green performance, the narrative from the gospel, will be sung in English, Munson said. That’s to better communicate the story to local listeners. The chorales and arias will be sung in the original German.