From TOLEDO MUSEUM OF ART

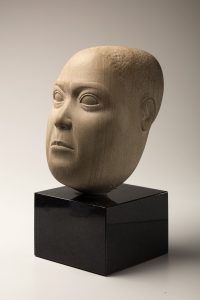

The Toledo Museum of Art (TMA) added more than 30 outstanding and diverse works of art to its collection in June through purchase and gifts. Among the many highlights of the new acquisitions are photographer Imogen Cunningham’s pioneering botanical study “False Hellebore (Glacial Lily)” (1926), Lonnie Holley’s incisive assemblage “Cutting Up Old Film (Don’t Edit the Wrong Thing Out)”(circa 1984), meditative still lifes by the 17th-century French painter Louyse Moillon and an anonymous 19th-century Mexican artist, and “Head of Charlie Parker” (circa 1955), a remarkable sculpture – never before exhibited publicly – by Los Angeles artist Julie Macdonald.

“The Toledo Museum of Art is grateful to welcome these outstanding and deeply resonant works of art to our galleries,” said Adam M. Levine, TMA’s Edward Drummond and Florence Scott Libbey director and CEO. “These new acquisitions broaden the narrative of art history we are able to tell and, in so doing, advance the culture of belonging we seek to create.”

TMA’s purchases encompassed 14 masterpieces from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, one of the most important collections of works of African American artists from the southern United States. The new acquisitions, as well as the 10 works of art previously acquired from the Foundation, will be highlighted in an upcoming exhibition, with details to be announced. Standouts added to TMA’s holdings this spring include metal assemblages by Ronald Lockett (“Verge of Extinction,” 1994) and Joe Minter (“How Do I Look?,”1997), a magnificent 1972 center medallion quilt by Estelle Witherspoon of Gee’s Bend, and Holley’s assemblage that incorporates film reel and scissors.

All of Holley’s work transforms discarded materials into powerful, often biting critiques of societal wrongs, from racial injustice and child neglect to environmental destruction. He frequently uses materials like old car parts and truck gears, electrical cords and recycled pieces of communication technology. In “Cutting Up Old Film (Don’t Edit the Wrong Thing Out),” Holley uses the found materials of an old film reel (including the film) with some editing scissors. As suggested by the title, the work is a social commentary on the construction of history, calling into question whose voices and perspectives become part of the official record and whose voices are “cut out” of the story.

Noted TMA supporters Mr. and Mrs. Spencer D. Stone generously gifted eight photographs to the Museum, including iconic modernist images by Imogen Cunningham (“False Hellebore (Glacial Lily),” 1926), Jacques-Henri Lartigue (“Paris, La Singer de Course: Bunny III, Avenue des Acacias,” 1912), Danny Lyon (“Crossing the Ohio River, Louisville” from “The Bikeriders,” 1966) and Barbara Morgan (“Merce Cunningham-Totem Ancestor,” 1942).

Titled with her subject’s horticultural name, Cunningham’s photograph is the first example of the artist’s highly regarded botanical images to enter TMA’s collection. In these photographs, the artist utilized luxuriant natural light, tight cropping and sharp focus to produce an abstracted image that celebrates the natural world’s formal beauty. Through this approach, she captures the graceful curves and characteristic ribbed texture of the plant’s leaves and transforms it from a common California plant into a sensual organic form. “False Hellebore,” together with the three existing Cunningham photographs in TMA’s collection, showcase the range of Cunningham’s vision, as well as her significant contributions to modernist photography.

Among the significant paintings acquired by TMA are two of the first Mexican works to enter the collection: the anonymous 19th-century still life of food, tableware and a parrot; and an 18th-century series of four full-length portraits of the Saints Jerome, Gregory, Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure by Andrés López. In addition, TMA purchased two rare still life paintings by European woman artists. Moillon’s “Still Life of Citrons and Curaçao Oranges in a White Polylobed Dish” (about 1630-34) entrances the viewer with its sense of mystery and sober reflection of the passage of time. And Victoria Dubourg’s “Still Life with Flowers and Peaches” of 1874 is a dramatically lit pyramid arrangement of bounty and introspection.

Macdonald’s “Head of Charlie Parker” was created at the apex of the artist’s career and was inspired by her close friendship with Parker, the legendary jazz soloist, which began in 1952. Parker was keenly interested in Egyptian statuary and the two frequently visited museums on his trips to Los Angeles. “Head of Charlie Parker” depicts a just over life-size bust of the work’s namesake in sandstone sourced from a Pasadena quarry. Parker’s expression is muted and pensive. Though a celebrated figure, he faced a lifetime of racism, hardship and loss, seemingly finding solace in music but also turning to unhealthy habits that would lead to his premature death. “Head of Charlie Parker” has never been exhibited publicly and relates to busts from the ancient to contemporary worlds represented in TMA’s collection, including ancient Egyptian sculpture, Yoruba visual traditions and Buddhist statuary.

TMA also purchased two recent glass works of art: Norwood Viviano’s “Recasting Toledo” (2021), which references Toledo and local sites; and Jiro Kamata’s “Holon Pipe” (2020), which features a mirror, gold and camera lenses in a fantastical combination.

Since its founding in 1901, the Toledo Museum of Art has earned a global reputation for the quality of its collections, innovative and extensive education programs and architecturally significant campus. Thanks to the benevolence of its founders, as well as the continued support of its members, TMA remains a privately endowed, non-profit institution and opens its collection to the public, free of charge. The Museum seeks to become the model art museum in the country, leading the way in genuinely and creatively engaging its communities and fostering a sense of belonging for all its audiences.