By JULIE CARLE

BG Independent News

Artificial intelligence may play an important role in combating low grain markets, increased costs and less profits in agriculture. AI applications such as precision agriculture, autonomous tillage and harvest automation are not just in the future, but happening now.

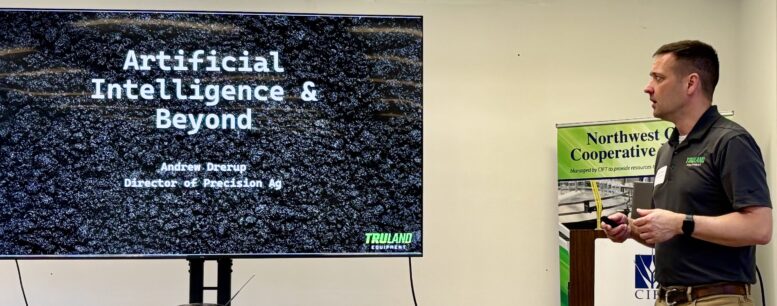

AI in agriculture aims to improve operational efficiency, reduce costs and labor needs and increase comfort for operators, Andrew Drerup, director of precision agriculture for Truland Equipment, said during the April CIFT Agribusiness Forum.

His company, a John Deere dealership, works with a wide range of agricultural customers from row crops and small grains to vegetables and hay or turf products. “We are seeing AI moving into every one of those aspects as we move forward,” he said. “In the last three to four years, it’s amazing how much we’ve actually started using it.”

With farmers in the midst of planting season, getting the seed in the ground as efficiently as possible is vital to helping the bottom line. AI helps increase efficiency and decrease expenses and labor needs.

“It handles the operation for us so we can focus on what’s going on. We can sit back and pay attention to what needs paid attention to, to visualize profit-loss,” he said. “We can easily pull data that shows us profit-loss across the field and in the end helps us through the tight times and helps us thrive in the good times.”

Many agricultural companies and other brands are adding AI to their products and services, Drerup said; however, because he has worked with John Deere for 23 years, his talk focused on Deere’s AI products.

The company’s AI technology called See & SprayTM was released three years ago using cameras attached to a sprayer boom that are focused about five to six feet ahead of the boom. The cameras are trained using AI to know what is or isn’t a weed based on the shape of the leaf.

The machine crosses the field at 12 to 15 miles per hour, scanning the ground, looking for anything that doesn’t look like the crop it is supposed to protect. It collects the images, sprays what needs spraying and sends images back to the processing center. The collected data helps refine the information for improved accuracy in the future.

Drerup said the cameras and sensors can identify and spray a weed as small as a quarter-inch. The accuracy at detecting and spraying weeds can result in a 60% reduction in chemical use for contact herbicides.

A co-op he is working with is testing one of the machines for efficiency. “They are used to spraying at 18 to 20 miles an hour, and with this technology, they are limited to 15. They want to see what the efficiency of the machine is to their current machines,” he said.

“It’s a little bit of a sticky subject for commercial applicators because they make their money selling chemicals. If I take 60% of their profit away, how do they make money?” he said.

Many companies will have to look at their services differently, possibly offering a subscription-based clean field model.

“There are always limitations with AI; it’s never perfect,” he said.

Speed is a limitation, along with the types of crops it works for. “We’re still building the crops we can do. For example, we can do corn, but we can’t do popcorn because the leaf structure is more like a grass,” he explained.

Autonomous tillage

“Anybody ever run a tillage tool through a field?It’s a lot of fun, isn’t it?” he joked. Autonomous tillage can help take the mundane out of farming.

Again, cameras are what makes autonomous tillage work. He admitted there are only a couple implements that work now.

“The tractor can run across the field, pick up the tool, turn around, drop the tool and go back across the field, completing at least 80% of the field without any human interaction,” Drerup said. Human involvement is necessary for finishing the outside round or two when it gets close to a road. The farmer will drive the tractor to the field, step out of the tractor and start the tractor via an app on the phone.

Customers often think they can send the equipment to the field and pick it up when it’s done, he said. “There’s a lot more to it than that, but they’ll get there. We’re going to get there faster, and faster than we’re probably comfortable with.”

Harvest autonomy is next

Harvest autonomy is in production now at John Deere.

“We’ve got quite a few combines coming in this year with it, utilizing cameras to do predictive adjustments and ground speed changes in the field,” he said. “Have you hit a green spot of soybeans when it’s really dusty and about to choke the combine out?”

The system utilizes satellite imagery that it records throughout the growing season. Cameras mounted on the front of the combine will look at the crop and make predictive changes before it hits that crop.

In a test last fall, the equipment was running in a dusty field of soybeans. The farmer with him knew there was a green spot in the field and was ready to slow the combine down manually.

Drerup told him, “It’s not your combine. We need to prove that this works. And sure enough, right before we hit that green spot, it pulled the speed back.” The combine also didn’t spit everything out the back, but kept the beans in the machine and changed back when it got through that patch.

Most operators can run their machines at 80 to 85% efficiency. The autonomous combine “is running 110% machine load, all day long, never changing. It pays for itself in the first year or so,” he said.

“That’s three of the probably best-use cases of where we’re seeing AI,” he said. “Every one of them uses cameras, and those camera images are going back and being processed, making adjustments in the field to increase efficiency. That’s the end goal here.”

Autonomous grain carts are being developed as well, eventually making farmers logistics managers rather than laborers.

AI technology beyond equipment

Deere dealerships are also using AI as part of their remote call center, but the calls don’t go to a foreign country or to people you don’t know. Whenever a call comes into the call center, information is collected, including the complaint, machine type, serial number, and model numbers. All of the information is part of a data library.

“The goal is always faster responses,” he said. “If we can’t resolve it via a phone call and need to send a technician out, by the time we are done talking to the customer, we can send the information to the local service department. That service manager has a complete log of everything we did, all the issues so the technician hits the field and has all that data and can even bring the parts they need because they know what’s wrong.”

Technology is also available for preventative maintenance. All of the modern equipment has cellphones that are connected to Deere to track the machines. When a machine starts accumulating hours, Deere can track the repairs that need to be done.

“We’re doing predictive diagnostics that save time and money,” he said. “It’s a whole lot easier to call a customer and say, ‘Hey, your fan drive system needs maintenance,’ rather than getting a phone call that says, ‘My fan drive just quit and I’m stuck in the field.’ It’s preventive maintenance rather than repairs.”

Software is one of the keys to the equipment running smoothly. Subscriptions are likely to be the new reality as a way to help companies fund advancements. “But there are benefits to the customer too,” Drerup said. “One is lower upfront costs.”

Instead of an operator needing to update equipment every couple of years as technology advances, “by doing a recurring license unit or subscription, we can keep that price down to where it’s more affordable.”